Sprint reportedly is going to enable " no incremental charge" calling when users of at least a couple of Sprint phones are in a Wi-Fi zone, without counting against a customer's voice usage cap.

As reported, a customer will simply need a compatible device (possibly Samsung S4 Mini or Galaxy Mega), enable the feature through a web interface and begin using it.

No monthly charge will be assessed for turning on Wi-fi Calling, apparently.

Offering such features ("free calling") often makes sense for a service provider when the risk of cannibalizing revenue is slight and when the network is lightly loaded enough that a significant increase in usage will not stress the network and when there are other business reasons for encouraging usage.

In this instance, the happy set of circumstances seems to include the fact that the Sprint 3G network will start to see less demand as traffic shifts to 4G (apparently the Wi-Fi calling feature requires presence of a 3G signal).

The Wi-Fi calls are domestic only, and of course all the leading national providers have found that voice usage keeps dropping anyhow, freeing up voice network capacity.

In this case the 3G network resource primarily used might only be the signaling network, as most of the time only the signaling network actually will be consuming network resources. Only in case of an emergency call being placed would actual bearer traffic be imposed on the 3G network.

The new feature also might create some distinctiveness for 3G network access, the supported handsets and Sprint's access services in general.

Thursday, January 16, 2014

Sprint to Enable Free Wi-Fi Calling?

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Spectrum Policy is Approaching a Revolution

In the United States, about half of all spectrum most suitable for communications, fixed and mobile, is licensed to various Federal government agencies, and, as you might well expect, much of that spectrum arguably is inefficiently managed.

Much of the new thinking centers on fundamental changes in the process whereby spectrum is made available for communications uses.

As a practical matter, though there are several ways to wring more effective use out of a finite spectrum resource, the absolute amount of spectrum useful for communications is limited.

As demand continues to grow, we bump up against physical constraints, even if demand shaping (Wi-Fi offload, tariffs), better technology (signal compression, better algorithms, agile frequency hopping) and network design (small cells, carrier Wi-Fi) can have meaningful impact.

Still, making better use of existing spectrum is among the tools policymakers can wield.

The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) report makes a couple of nearly-revolutionary statements. Among the observations is the impractical method traditionally used to reclaim and then commercialize spectrum (“clear and auction”), simply because the costs of transition are so high.

The other really-novel insight is the observation that assigning spectrum in slivers, each with an assigned application profile, is inefficient, in light of modern technology.

In the wireless and mobile communications business, spectrum exhaust is a perennial problem. But there is new thinking that perhaps such scarcity is perhaps partly a result of allocation policies, not an absolute “shortage” of spectrum as such.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

2014 Telecom Revenue Growth Picture is Mixed

Of all the trends affecting the global telecom business since the advent of competition, nothing is more striking than diverging strategy and revenue performance.

For example, telecom service providers in Asia and North America are posting three perent to four percent annual revenue growth, while revenues in Europe have been dropping for some years.

Moody's Investors Service has said the outlook for telecommunications service providers is “stable” in the Asia Pacific region, with “ moderate revenues and earnings growth” and gradual declines in profit margins.

"The telecommunications companies that we rate in Asia Pacific should record average revenue growth of around four percent over the next 12 months to 18 months, a level which is broadly in line with average GDP growth rates in the region," says Yoshio Takahashi, a Moody’s analyst.

In contrast, Europe's telecom operators will see a fifth year of revenue decline in 2014, although operating margins will stabilize, helped by cost cutting and the end of regulatory cuts to mobile call termination fees, Moody's said.

About the best outcome would be “revenue stabilization” in 2014, Moody’s says, with the telecommunications service sector remaining on negative outlook.

"While we expect revenues to stabilize or marginally decline by zero percent to -0.5 percent in 2014, it is not clear how sustainable any recovery will be," said Carlos Winzer, a Moody's Corporate Finance group SVP. "We have had a negative outlook on the sector since November 2011 and would expect to see a predictable and sustainable one percent to three percent annual revenue growth to make it stable."

Moody's estimates that the European industry's average EBITDA margin will be down approximately one percent in 2013, but will probably stabilize in 2014.

In Latin America, Moody’s think both 2013 and 2014 will be good years. Moody's says South African, Russia as well as Middle East, market trends are more stable than in Europe.

In the U.S market, the mobile segment of the business “will continue to generate strong levels of free cash flow,” acording to Moody’s. Earnings (EBITDA) minus capital spending growth, a proxy for free cash flow, will accelerate to 13 percent to 15 percent in 2014 for the six largest carriers.

“We also expect overall industry EBITDA to gain eight percent next year as industry service revenues grow three percent to four percent,” Moody’s forecasts.

Moody's expects that prices in some of the most competitive European markets will continue to drop Integrated incumbent operators such as Deutsche Telekom, Orange, KPN, Telefonica and Portugal Telecom will fare better than companies with just mobile or fixed offerings.

That’s an important observation: the firms that will fare best own both fixed and mobile assets. The other obviously significant observation is that revenue growth rates now have diverged around the world, with some regions faring better than others.

Despite the tough European conditions, or perhaps because revenues are challenged, Moody’s forecasts an average capex/revenue ratio of approximately 18 percent or higher in 2014.

In Asia, Moody’s predicts mobile service provider capex will decline to about 20 percent of revenue in 2014.

But it is possible European capital investment could increase, especially as Vodafone begins to upgrade its networks and other competitors invest to keep up.

But Asia remains a bright spot for the global industry. Moody's forecasts average adjusted EBITDA margins in the region will contract by approximately 0.5 percent to one percent in 2014.

"Increased data usage on mobile phones will continue to drive the Asia Pacific industry's revenue growth, although rising mobile-penetration rates and competition will slow the pace of growth,” Moody’s said.

But profit margins will stay at 37 percent to 38 percent. The area to watch in Asia is financial leverage, which will remain “moderately high,” Moody’s says, as the companies deploy excess cash to increase shareholder returns, rather than significantly reducing debt.

While specific in-market consolidation deals may be completed in the next 12 months to 18 months in Europe, Moody's does not expect a wave of cross-border consolidation.

The four largest integrated incumbent telcos, including Telefonica, Deutsche Telekom, Orange and Telecom Italia, are either in selling mode or do not have much flexibility or appetite to lead this process.

But that obviously should shift attention to U.S., Mexican or other potential acquirers.

The main point is that competition now has lead larger telecom providers to diverge, in terms of strategy, revenue models and actual revenue growth.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

HP to Sell "Voice Tablets" in India

IDC reports that phones with screen sizes ranging from five to seven inches grew 17 times in the second quarter of 2013, year over year.

In the third quarter of 2013, IDC said phablets accounted for 23 percent of the overall market for phones.

Some of us might note that such purchasing patterns suggest the decades long effort to create $100 PCs for developing nations has been eclipsed by commercial offerings that serve the same purpose.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Skype-to-Skype International Call Volume Up 33% in 2013

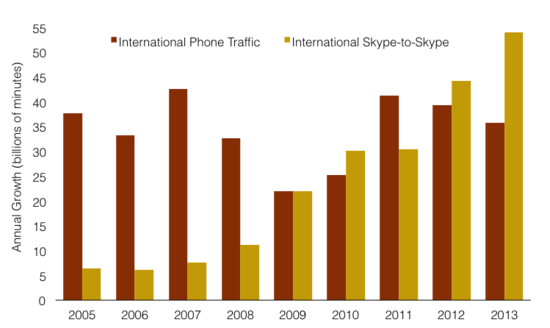

Some recent patterns in international voice have not changed: Skype keeps growing, but so does the volume of carrier voice. But prices per minute of usage also continue to decline.

Skype’s on-net (Skype to Skype) international traffic grew 36 percent in 2013, to 214 billion minutes, says Telegeography.

Generally speaking, Skype-to-Skype volume growth has outpaced carrier voice since about 2009.

International telephone traffic from fixed and mobile phones continues to grow as well, increasing seven percent in 2013, to 547 billion minutes.

However, recent growth rates are well below the 13 percent average that carriers posted over many of the past 20 years, and the benefits of traffic growth have largely been offset by steady price declines, Telegeography notes.

Skype added 54 billion minutes of international traffic in 2013, 50 percent more than the combined international volume growth of every telco in the world, says Telegeography.

Increase in International Phone and Skype Traffic, 2005-2013

Source: TeleGeography

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Tuesday, January 14, 2014

Appeals Court Strikes Down "Network Neutrality" Rules

A Federal appeals court has struck down current network neutrality rules, largely on procedural grounds.

The decision issued by the District of Columbia circuit court says that the Federal Communications Commission does not have authority to issue network neutrality rules, which essentially mandate “best effort only” retail Internet access offers, on fixed networks. The FCC rules had exempted mobile Internet access services, at least for the moment.

The DC circuit court’s decision in Verizon v. FCC means the 2010 net neutrality rules are rescinded.

To be sure, the matter is not fully settled. An appeal might be launched. And Congress has the authority to pass legislation giving the FCC authority to impose net neutrality rules.

Most might conclude it is unlikely that Congress will do so in the near term. The court did not strike all the rules. A consumer protection clause, requiring ISPs offering quality of service features to disclose that fact to end users, remains in force.

As with earlier strife over such rules, a public policy objective (Internet access should only be allowed on a “best effort” basis) reflects a mix of corresponding private interests and a healthy dose of conflict between legacy regulatory models.

At the heart of the question is the proper regulatory format for an Internet access service, with potential models arguably representing some mix of a legacy “common carrier” approach with a “content industry” framework.

And that’s the rub. Traditionally, content providers essentially have been unregulated, with data services seen in that manner. Common carrier regulation has been the rule for “telephone” services.

In between are the “broadcast and cable company” models, which involve a mix of rules, less restrictive than common carrier rules, but more restrictive than pure content company rules (newspapers, magazines).

So network neutrality is an issue not only because huge business interests are lined up on opposite sides of the argument about whether best effort access and quality-assured access can coexist, but also whether ISP access business models necessarily restrict freedom and innovation for Internet application providers.

The argument on one side is that allowing ISPs to create content delivery networks maintaining or boosting quality of experience for applications using such CDN services necessarily alters the “open” nature of Internet app development.

The opposing argument is that content delivery networks already are routinely purchased by application providers, over the Internet backbone, and nobody seems to think that is inherently anti-competitive.

The larger problem is that the Internet supports multiple media types and revenue models that make a mockery of traditional regulatory frameworks.

When voice, text communications, “print” content, video entertainment, business apps and retailing all occur over the Internet, should some revenue models be outlawed as incompatible? Or should all lawful revenue models be allowed?

As an analogy, if a customer wants to buy, and a provider wants to sell, video entertainment with varying levels of quality (less than standard definition, standard definition TV, high definition and 4K), should that be possible?

And if, to make that possible, access traffic has to be shaped, should the shaping be unlawful? As video providers routinely impose higher costs for consumers to receive content with HDTV resolution, should ISPs be able to charge for the higher costs of delivering such content?

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Monday, January 13, 2014

Sprint Ends "One Up" Frequent Device Upgrade Program; the Issue is Why

It isn’t completely clear why Sprint has decided to end its One Up program that allowed users to upgrade devices more often, as the other major carriers earlier had decided to do as well. But Sprint’s launch of new “Framily” plans might have something to do with the rationale.

First, consider why carriers decided to change policies on device subsidies in the first place. In part, the thinking was that some customers really did want to upgrade devices more often than every 24 months. So the One Up program was intended as a response to such demand.

But Sprint might have found that actual use of the program wasn’t as high as some had thought. On the other hand, by some estimates, perhaps 40 percent of account holders, with multiple lines on each account, would consider switching plans, but are deterred by early contract termination fees.

That is why both T-Mobile US and AT&T Mobility are trying to lure customers on such plans by agreeing to pay the ETF fees when an account switches.

Perhaps Sprint concluded that the bigger upside, either in terms of customer retention, or customer acquisition, is not so much related to phone upgrades, but keeping and getting multi-line accounts.

Sprint’s “Framily” plan formalizes the process of creating “family” or multi-user accounts including unrelated persons, billing each account separately though applying discounts as though all were on a single family plan.

There are other possible explanations for what seems a rather abrupt shutdown of the device upgrade plans. Sprint might be closer to launching some other initiatives deemed more important, and no carrier wants to support too many different programs all at once.

But one might guess that Sprint already has discovered that there actually is less demand for rapid device upgrades than it had expected, or that the battle over mulit-user accounts now seems the most-important customer segment to protect and grow.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Directv-Dish Merger Fails

Directv’’s termination of its deal to merge with EchoStar, apparently because EchoStar bondholders did not approve, means EchoStar continue...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...