Deutsche Telekom has transferred its 67 percent stake in T-Mobile US into a different holding company offering tax advantages in the event of a sale of T-Mobile US. That doesn't mean any sale is imminent, but does suggest it is viewed as a reasonable development by Deutsche Telekom.

Soon, the attention will shift to which buyer emerges, and then whether U.S. regulators will allow the transaction to proceed. Deutsche Telekom has been there before, as the proposed AT&T acquisition was abandoned because of regulatory and antitrust opposition.

It won't be especially easier this time around, either.

Friday, January 17, 2014

Deutsche Telekom Puts T-Mobile US Asset Where a Sale Would be More Advantageous

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

To "Move the Needle" on Market Share, Mobile Carriers Must Win"Family" Plan Accounts

Over the past decade or so, a big change in retail mobile service plans has happened. In the business as a whole 68.5 percent of postpaid customers are on family plans. Just 26 percent of plans are “individual” plans.

About five percent of the market consists of business-paid accounts.

Verizon has 72 percent of its customers on family plans and seven percent on corporate plans.

There are all sorts of practical implications. For starters, any disruptive attack on market share almost has to affect the family plans, since they represent about 69 percent of the customer base.

The other practical matter is that one would get a wrong result when comparing “individual plans” across countries, especially where most of the buyers are prepaid, not postpaid, and where most sales are of “individual” plans, not “family” plans.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Are U.S. Mobile Carriers Customer Bases Differentiated?

It is a commonplace observation that the largest four U.S. mobile service providers are differentiated on the dimensions of churn and average revenue per account. Basically, Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility customers churn at half the rate of Sprint and T-Mobile US customers.

But there might also be a significant differentiation based on why customers choose their service providers.

When Cowen and Company analysts asked customers why they chose their service provider, AT&T and Verizon chosen for "network coverage and quality,"

Sprint was chosen for "unlimited data plan and better price," while T-Mobile US likewise was chosen for "better price and unlimited data plan.

The distinctions are clear: customers who value coverage and quality tend to buy AT&T and Verizon. Customers who value unlimited data and price chose Sprint and T-Mobile US.

So the question, assuming you believe a big marketing war will escalate, is how big each of those customer segments are. For that might limit the gains either Sprint or T-Mobile US can gain and hold, over the long term.

It will be easier for AT&T and Verizon to match price offers than for T-Mobile US and Sprint to dramatically expand their footprints.

But all that assumes no major change in market structure. With the possibility that something happens with T-Mobile US (merger with another provider), and if Dish Network does enter the market, along with activation of assets from one or two of the mobile satellite firms that want to repurpose their mobile satellite spectrum, tomorrow's market could look different.

But that will occur within a context where it appears customers fall into two broad camps: buyers who value coverage and quality, even at higher price; and customers who value unlimited usage and want lower price.

Coverage might not matter for the latter, while lower price, while helpful, still is not why the former customers make their fundamental choices.

How much the contestants can structure their operations to attract the "other" type of customer will become a bigger issue.

But there might also be a significant differentiation based on why customers choose their service providers.

When Cowen and Company analysts asked customers why they chose their service provider, AT&T and Verizon chosen for "network coverage and quality,"

Sprint was chosen for "unlimited data plan and better price," while T-Mobile US likewise was chosen for "better price and unlimited data plan.

The distinctions are clear: customers who value coverage and quality tend to buy AT&T and Verizon. Customers who value unlimited data and price chose Sprint and T-Mobile US.

So the question, assuming you believe a big marketing war will escalate, is how big each of those customer segments are. For that might limit the gains either Sprint or T-Mobile US can gain and hold, over the long term.

It will be easier for AT&T and Verizon to match price offers than for T-Mobile US and Sprint to dramatically expand their footprints.

But all that assumes no major change in market structure. With the possibility that something happens with T-Mobile US (merger with another provider), and if Dish Network does enter the market, along with activation of assets from one or two of the mobile satellite firms that want to repurpose their mobile satellite spectrum, tomorrow's market could look different.

But that will occur within a context where it appears customers fall into two broad camps: buyers who value coverage and quality, even at higher price; and customers who value unlimited usage and want lower price.

Coverage might not matter for the latter, while lower price, while helpful, still is not why the former customers make their fundamental choices.

How much the contestants can structure their operations to attract the "other" type of customer will become a bigger issue.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Spectrum Management Heading for a Historic Change

Spectrum not only is the foundation for all wireless and mobile services, it is a foundational matter for would-be service providers. And big changes are coming.

New spectrum formerly used for TV broadcasting is being reallocated to mobile communications. And at least some of that reallocation process will involve methods of adjusting the behavior of networks and devices dynamically, based on interference issues.

New thinking is happening about sharing existing spectrum as well. It simply is too expensive and time-consuming to conduct widespread "clear and auction" operations across much of the communications-capable spectrum below 3 GHz.

So much attention now is focused on how existing licensed users can be persuaded to share their frequencies with new commercial users as well. Incentives will play a key role: existing licensees will have to see clear financial benefits for doing so, and since so much licensed spectrum below 3 GHz is licensed to government and military users, such incentives will be tricky.

And the ways mobile operators use mobile licensed spectrum, unlicensed spectrum and fixed network assets is changing. Already, even without formal business relationships, perhaps 60 percent to 80 percent of mobile device Internet access occurs on Wi-Fi connections.

Some would say that reveals a key strategic weakness for mobile operators, whose costs of providing Internet bandwidth are too high to survive massive adoption of mobile video consumption.

And though there is more attention paid to global standards, the U.S. market will in some ways remain a bit different.

In some ways, the continental-sized U.S. market has allowed the U.S. communications business to develop based at times on local standards not shared with most of the rest of the world. The primary past example is use of CDMA air interfaces alongside GSM, where in most of the rest of the world GSM was the sole standard.

Frequency plans within the United States will be the salient example of this in the next phase of the mobile business, as most of the rest of the world tries to create a common 700-MHz band for mobile communications across Europe, Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Once again, because of past spectrum allocation decisions, the U.S. will remain a market without full frequency harmonization with most of the rest of the world. How important that might be is not so clear, though.

Global frequency coordination is helpful for manufacturers, as it allows more scale when developing handsets. It is helpful for international travelers who then can roam almost at will when traveling (assuming they don’t mind the international tariffs).

But advances in radio agility are important. In principle, it is possible to equip a device for frequency agility that can compensate for different frequencies used in different countries. And since all mobile carriers have agreed on Long Term Evolution as the common air interface standard (even if there are differences in modulation), frequency might ultimately be less an issue.

The issue for European regulators and industry concerns is whether the 2012

World Radiocommunication Conference of 2012, which decided to open up the 700MHz band across the EMEA region for mobile communications, will be able to come up with enough consensus to allow a further decision at the 2015 WARC meeting.

Of course, that process will be contentious, as TV broadcasters will have to be induced to surrender their use of spectrum to mobile interests. That has not proven easy, wheneve it has had to happen.

But such decisions now are among the growing range of ways national regulators are playing a fundamental role in setting the stage for the next phase of mobile communications growth. Though observers might disagree on how much additional spectrum is required, nearly everybody believes more spectrum will be needed.

And much of the focus will be on ways to find new ways to use spectrum already licensed for some other purpose, to some other users, as very little of the spectrum most useful for communications actually is unclaimed. That means a historically new look at ways to enable sharing of licensed spectrum, more use of frequency-agile networks and devices, and a new business role for unlicensed spectrum.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Thursday, January 16, 2014

Erosion of Subscription Video is About 1% a Year

The strategic problem faced by traditional video subscription services is not that massive customer desertion is happening now. In fact, attrition, though real, is rather low at the moment.

According to The Diffusion Group, nearly 88 percent of all adult broadband Internet access users in the United States subscribe to a cable, satellite, or telco-TV service.

“The notion that we’re on the edge of a ‘mass exodus’ from incumbent pay-TV services to online substitutes is not supported by the data,” says Michael Greeson, co-founder of TDG and director of research.

The longer term problem is that younger consumers do not seem to buy the product as heavily as older consumers. And unless that changes, trouble lies ahead.

For example, TV subscription rates among those 25 to 34 are 82 percent, and 85 percent among those 18 to 24.

Note that the TDG metric is adoption of subscription TV among “broadband households.”

Of course, since household adoption of broadband Internet access is itself a percentage of all occupied U.S. homes, the adoption of video entertainment services as a percentage of all occupied U.S. homes might be lower than 88 percent.

U.S. broadband penetration is estimated at 78 percent of U.S. homes. If 88 percent of those homes buy a video service, then video penetration hypothetically (some homes buy video service but not broadband or dial-up access) could be as low as 69 percent.

Nobody believes video subscription rates are that low, estimating that more than 102 million U.S. homes actually buy a subscription. That compares to about 115.6 million TV households altogether, including homes that only watch over the air TV.

If there are about 130 million occupied homes, that implies video subsription penetration of about 78 percent, oddly enough the same penetration rate as broadband.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

60% of Surveyed Rural Telcos Offer Mobile, Fixed Wireless Services

Some 60 percent of about 31 rural telcos surveyed by NTCA:The Rural Broadband Association report they are providing “wireless service” to their customers, including both mobile and fixed wireless services, using a mixture of owned spectrum and facilities as well as resale or agency agreements with mobile service providers.

About 28 percent of those respondents offering mobile service resell another carrier’s service under their own brand, and 21 percent do so under a national brand. So 39 percent “resell” or have an agency agreement.

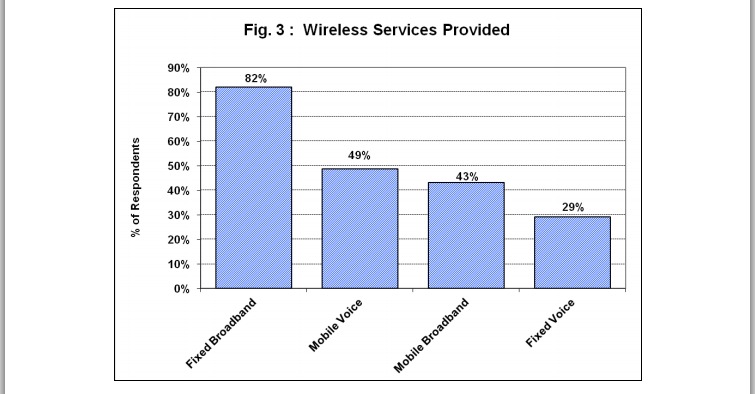

Some 82 percent sell fixed broadband Internet access (29 percent say they also sell fixed voice using wireless), while 49 percent sell mobile services.

Of the respondents not currently offering wireless or mobile service, some 30 percent are considering doing so.

About 60 percent of independent and smaller rural U.S. telcos surveyed by NTCA:The Rural Broadband Association report they own at least one wireless license in the frequency range

Some 70 percent of carriers owning a license below 2.3 GHz have a 700 MHz license, 47 percent have an AWS license, 47 percent a PCS license, 13 percent some other license

(such as microwave), 11 percent cellular, six percent paging, and two percent SMR. For the most part, those are “access” frequencies.

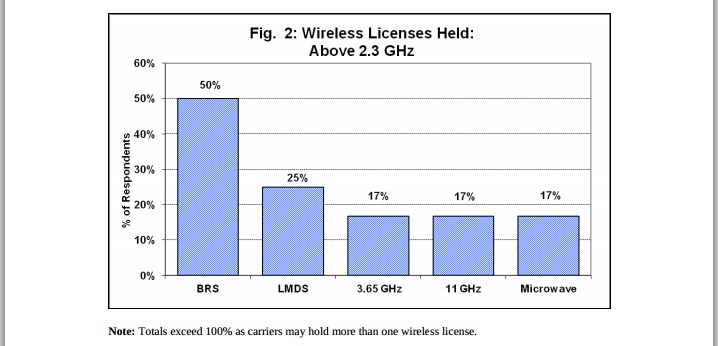

About 21 percent of the 31 reporting companies hold at least one license above 2.3 GHz. About half of service providers holding a license above 2.3 GHz have a BRS license, 25 percent an LMDS license, 17 percent a 3.65 GHz, 17 percent a license at 11 GHz, and 17 percent a microwave license. While BRS and LMDS are “access” frequencies, the others likely are used for trunking.

The average cumulative investment in wireless facilities, excluding spectrum, is

$6.2 million, while average cumulative investment in spectrum totaled $646 thousand.

About 46 percent of respondents are using unlicensed spectrum to provide some

wireless services.

About 28 percent of those respondents offering mobile service resell another carrier’s service under their own brand, and 21 percent do so under a national brand. So 39 percent “resell” or have an agency agreement.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Sprint Can Get Financing for T-Mobile Bid

Sprint reportedly has gotten assurances from at least

o banks about the feasibility of raising enough money to finance a takeover of T-Mobile US.

The proposals envision a total enterprise value (value of outstanding equity and debt) of about $50 billion for the deal.

It might cost $31 billion to buy all T-Mobile US shares and then also raise about $20 billion to cover the cost of assuming existing T-Mobile debt.

But financing is likely to be the least of concerns about any such combination. The bigger issues involve antitrust clearance and approval by the Federal Communications Commission, since the U.S. Department of Justice already has said it considers the U.S. mobile market too concentrated already.

o banks about the feasibility of raising enough money to finance a takeover of T-Mobile US.

The proposals envision a total enterprise value (value of outstanding equity and debt) of about $50 billion for the deal.

It might cost $31 billion to buy all T-Mobile US shares and then also raise about $20 billion to cover the cost of assuming existing T-Mobile debt.

But financing is likely to be the least of concerns about any such combination. The bigger issues involve antitrust clearance and approval by the Federal Communications Commission, since the U.S. Department of Justice already has said it considers the U.S. mobile market too concentrated already.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Directv-Dish Merger Fails

Directv’’s termination of its deal to merge with EchoStar, apparently because EchoStar bondholders did not approve, means EchoStar continue...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...