It is easy, but perhaps wrong, to attribute many types of change to “Covid-19” or the responses made to the pandemic. To be sure, the prevalence of work-from-home, learn-from-home modes required by governments to slow the spread was a precipitating event. It arguably speeded up trends already in place and convinced larger numbers of people and firms to consider joining trends, such as substituting Zoom video conferences for older meeting formats.

With good reason, increased amounts of work from home are viewed as a permanent shift in venues where many types of work are done on a routine basis. The conventional wisdom is that hybrid models will dominate, with more workers spending parts of the week working from home, rather than “in the office.”

source: Researchgate

But it is worth noting that this “remote work” trend has been in place and growing for more than 50 years, though we used to call it “telecommuting.”

source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

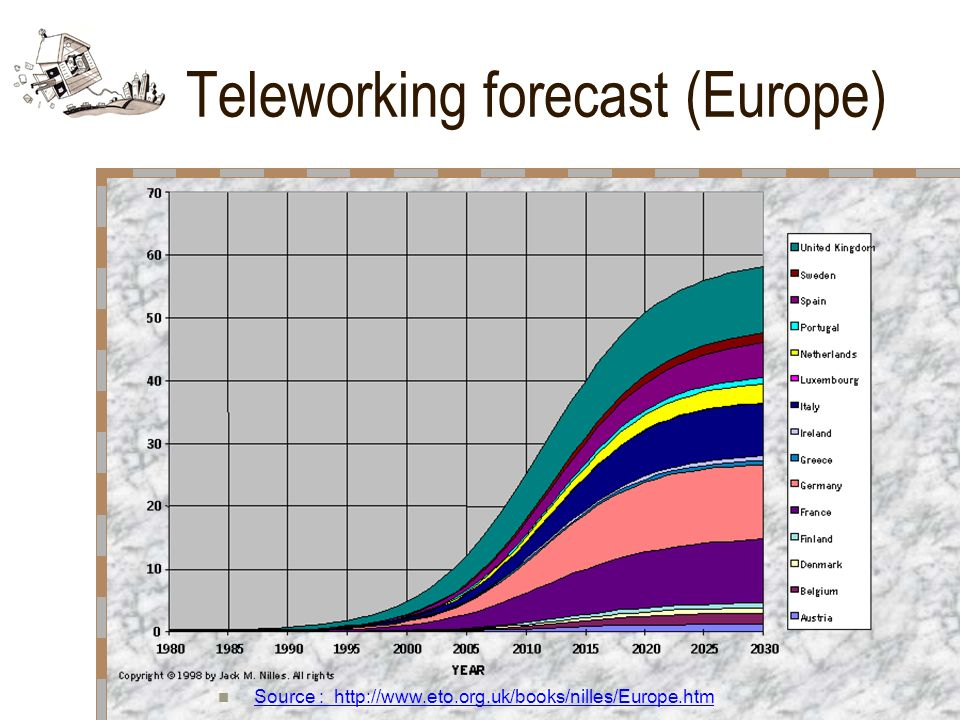

The point is that forecasters have expected a huge increase in remote work patterns for quite some time.

Source

So it might be safe to say that belief in permanent change of remote work arrangements will happen. But the change might be more gradual than some believe.

There might be unexpected barriers in the form of cost issues, as has proven true in the past, for at least some firms.

More importantly, it is hard enough to measure office worker productivity at all. It will be devilishly difficult to determine what impact on productivity remote work in large doses might produce.

Obviously, at some level of productivity (higher, same, lower), many types of work can be performed remotely, at home.

source: McKinsey

But productivity is an issue. To be sure, most of us assume that higher investment and use of technology improves productivity. That might not be true, or true only under some circumstances.

Investing in more information technology has often and consistently failed to boost productivity. Others would argue the gains are there; just hard to measure. There is evidence to support either conclusion.

Most of us likely assume quality broadband “must” boost productivity. Except when it does not. The consensus view on broadband access for business is that it leads to higher productivity.

But a study by Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute finds “small positive associations between broadband and firms’ productivity levels, none of these effects are statistically significant.”

“We also find no significant effect looking across all service sector firms taken together,” ESRI notes. “These results are consistent with those of other recent research that suggests the benefits of broadband for productivity depend heavily upon sectoral and firm characteristics rather than representing a generalised effect.”

“Overall, it seems that the benefits of broadband to particular local areas may vary substantially depending upon the sectoral mix of local firms and the availability of related inputs such as highly educated labour and appropriate management,” says ESRI.

Most of us are hopeful about the value of internet of things. But productivity always is hard to measure, and is harder when many inputs change simultaneously. Consider the impact of electricity on agricultural productivity.

“While initial adoption offered direct benefits from 1915 to 1930, productivity grew at a faster rate beginning in 1935, as electricity, along with other inputs in the economy such as the personal automobile, enabled new, more efficient and effective ways of working,” the National Bureau of Economic Research says.

There are at least two big problems with the “electricity caused productivity to rise” argument. The first is that other inputs also changed, so we cannot isolate any specific driver. Note that the automobile, also generally considered a general-purpose technology, also was introduced at the same time.

Since 1970, global productivity growth has slowed, despite an increasingly application of technology in the economy overall, starting especially in the 1980s.

A corollary: has information technology boosted living standards? Not so much, some say. The absence of huge productivity gains has created what economists call the “productivity paradox.”

Basically, the paradox is that the official statistics have not borne out the productivity improvements expected from new technology.

Still, the productivity paradox seems to exist. Before investment in IT became widespread, the expected return on investment in terms of productivity was three percent to four percent, in line with what was seen in mechanization and automation of the farm and factory sectors.

When IT was applied over two decades from 1970 to 1990, the normal return on investment was only one percent.

This productivity paradox is not new. Information technology investments did not measurably help improve white collar job productivity for decades. In fact, it can be argued that researchers have failed to measure any improvement in productivity. So some might argue nearly all the investment has been wasted.

Some now argue there is a lag between the massive introduction of new information technology and measurable productivity results, and that this lag might conceivably take a decade or two decades to emerge.

Work from home trends were catalyzed by the pandemic, to be sure. Many underlying rates of change were accelerated. But the underlying remote work trends were there for decades, and always have been expected to grow sharply.

Whether that is good, bad or indifferent for productivity remains to be seen. The Solow productivity paradox suggests that applied technology can boost--or lower--productivity. Though perhaps shocking, it appears that technology adoption productivity impact can be negative.