Many will criticize telco failures to "innovate." Many will pan diversification efforts such as that made by AT&T into content ownership and entertainment video services. By one reckoning, AT&T actually did quite well.

Many will criticize telco failures to "innovate." Many will pan diversification efforts such as that made by AT&T into content ownership and entertainment video services. By one reckoning, AT&T actually did quite well.

It actually took only a handful of attempts before AT&T was able to emerge as a significant provider of video content, video subscriptions and internet access. In fact, it did not actually take many tries before AT&T and Verizon actually created roles for themselves in content and video.

On June 24, 1998, AT&T acquired Tele-Communications Inc. for $48 billion, marking a reentry by AT&T into the local access business it had been barred from since 1984.

Having spent about two years amassing a position in local access using resold local Bell Telephone Company lines, AT&T wanted a facilities-based approach, and believed it could transform the largely one-way cable TV lines into full telecom platforms.

That move was but one among many made by large U.S. telcos since 1994 to diversify into cable TV, digital TV, satellite TV and fixed wireless, mostly with an eye to gaining share in broadband services of a few different types.

By some accounts, TCI was at the time the second-largest U.S. cable TV provider by subscriber count, trailing only Time Warner. TCI had 33 million subscribers at the time of the AT&T acquisition. As I recall, TCI was the largest cable TV company by subscribers.

For example, in 2004, six years after the AT&T deal, Time Warner Cable had just 10.6 million subscribers. In 2000, by some estimates, Time Warner had about 13 million subscribers. That undoubtedly is an enumeration of “product units” rather than “accounts.” Time Warner reached the 13 million account figure by about 2013, according to the NCTA.

Since 1994, major telcos had been discussing--and making--acquisitions of cable TV assets. In 1992 TCI came close to selling itself to Bell Atlantic, a forerunner of Verizon. Cox Cable in 1994 discussed merging with Southwestern Bell, though the deal was not consummated.

US West made its first cable TV acquisitions in 1994 as well. In 1995 several major U.S. telcos made acquisitions of fixed wireless companies, hoping to leverage that platform to enter the video entertainment business. Bell Atlantic Corp. and NYNEX Corp. invested $100 million in CAI Wireless Systems.

Pacific Telesis paid $175 million for Cross Country Wireless Cable in Riverside, Calif.; and another $160 to $175 million for MMDS channels owned by Transworld Holdings and Videotron in California and other locations.

By 1996 the telcos backed away from the fixed wireless platforms. In fact, U.S. telcos have quite a history of making big splashy moves into alternative access platforms, video entertainment and other ventures, only to reverse course after only a few years.

But AT&T in 1996 made a $137 million investment in satellite TV provider DirecTV.

Microsoft itself made an investment in Comcast in 1997, as firms in the access and software industries began to position for digital services including internet access, digital TV and voice services. In 1998 Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen acquired Charter Communications and Marcus Cable Partners.

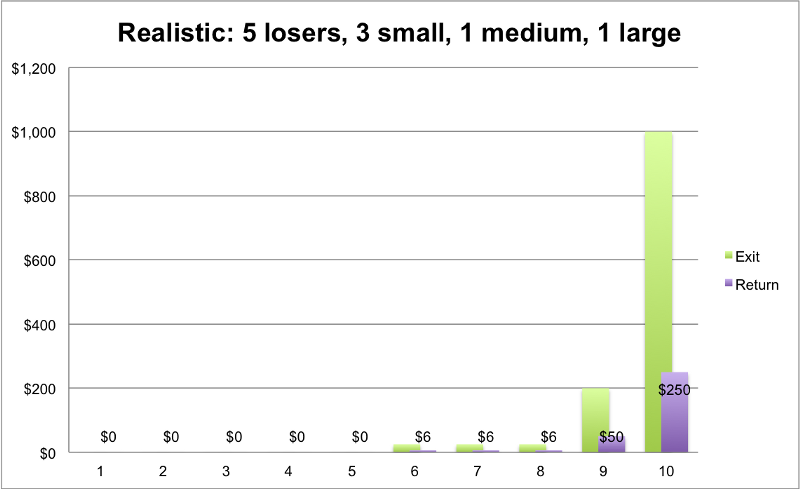

Those efforts, collectively, are well within the “one success in 10” rule of thumb, for any single firm, and close to it for the entire industry. More significantly, the amount of revenue generated by those efforts come well within the “one in 100” rules of innovative success for “blockbuster” impact.

AT&T, remember, continues to own 70 percent to 80 percent of its former Time Warner content assets. It continues to benefit from the cash flow of DirecTV and its fixed network video services. It continues to drive cash flow from HBO Max.

And all that was achieved with far fewer than 10 attempts. By standard metrics of innovation, that clearly beats the odds.

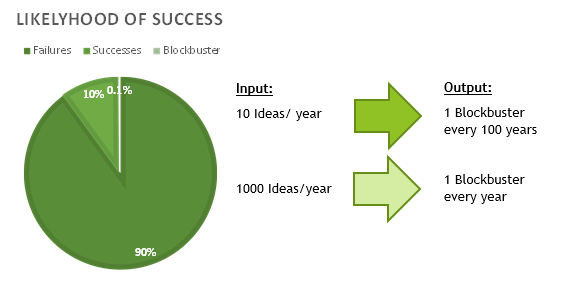

What most will miss is the difficulty of making successful change in any organization, on a routine basis. As a rule of thumb, only about one in 10 efforts at change will succeed. Quite often, only about one in 100 successful innovations is truly consequential in terms of organization performance.

source: Organizing4Innovation

That means we must tolerate a high rate of failure before we can hope for successful change. And we must fail quite a lot before we encounter a successful innovation with the power to change a company's or a whole industry's fortunes.

Of all the innovations connectivity providers have attempted--and been criticized for--how many have had industry-altering implications? Not many. Fixed network voice; mobile phones; internet access and possibly entertainment video subscriptions have been transformative.

Deregulation, privatization and competition have been historically transformative. But one might argue that was something that "happened to" the connectivity business, not necessarily an innovation of the industry itself.

Yes, we have seen many generations of business data networking services and business phone systems and services. But few have revenue magnitudes so great they change the fortunes of the industry or whole firms. In 150 years, only mobility and internet access have had clear industry-altering implications.

We all are familiar (even when we do not know it) with the sigmoid curve, otherwise know as the S curve, which describes the normal adoption curve for any successful product. We are less familiar with the idea that most innovations fail, whether that is new products, new technologies, new information technologies or business strategies.

S curves apply only to successful innovations.

Most new products simply fail. In such cases there is no S curve. The “bathtub curve” was developed to illustrate failure rates of equipment, but it applies to new product adoption as well. Only successful products make it to “userful life” (the ascending part of the S curve) and then “wearout” (the maturing top of the S curve before decline occurs).

source: Reliability Analytics

Though nobody “likes” to fail, there is good reason for the advice one often hears to “speed up the rate of failure.” The advice is quite practical.

Only about one in 10 innovations actually succeeds. Those of you who follow enterprise information technology projects will recognize the pattern: most efforts at IT change actually fail, in the sense of achieving their objectives.

source: Organizing4Innovation

“We tried that” often is the observation made when something new is proposed. What almost always is ignored is the high rate of failure for proposed innovations. About nine out of 10 innovations will probably fail. Most of us are not geared to handle that high rate of failure.

Unwillingness to make mistakes almost ensures that an entity will fail in its efforts to grow, innovate or even survive.

Those of you who follow startup success will recognize the pattern as well: of 10 funded companies only one will really be a wild success. Most startups do not survive.

source: Techcrunch

Connectivity providers are not uniquely free from the low success rate of most innovations. Innovation is hard. Most often efforts at innovation will fail. Even smaller efforts will fail nine times out of 10. An industry-altering innovation might happen only once in 100 attempts.

The more failure, the more the chances for eventual success. Many would consider telco initiatives in content and video subscriptions to have "failed." It is more accurate to call them an innovative success, given the relative handful of attempts to lead that business.

AT&T continues to own 70 percent of its former Time Warner content assets. It continues to benefit from the cash flow of DirecTV (about 71 percent ownership) and its fixed network video services. It continues to drive cash flow from HBO Max.

And all that was achieved with far fewer than 10 attempts. By standard metrics of innovation, that clearly beats the odds.