Sunday, May 23, 2010

Does Intense Price Competition Drive U.S. Wireless Industry Concentration?

The important observation is that, in some markets, even high levels of supplier concentration do not preclude important, even robust levels of competition, on price, quality and other dimensions.

When analyzing levels of competition in a market, economists often, and rationally, infer it from the level of industry concentration, where higher levels of concentration indicate the presence of market power. But industry concentration is related to the size of a market as well as high sunk costs or intense price competition, or some combination.

High industry concentration can be the result of a limited market or high fixed costs, as for a water, electricity or wastewater system, for example, all cases where fixed costs are so that facilities-based competition is not possible.

In some other markets, high capital investment requirements can create huge barriers to entry. Where that barrier exists, even when competition increases because of new entrants in a market, market concentration could still increase, even in the face of price competition. Market concentration appears to reach a lower bound, despite continuing growth in the size of the market.

It is possible that the apparent lower bound on market concentration could reflect economic and technological constraints that continuing growth in the number of competitors will not, and cannot, affect. In other words, some markets might always feature few competitors, for logical reasons. Few today would agree that telecommunications is a natural monopoly. But neither would many agree that the number of facilities-based contestants can be a large number.

The video entertainment market is less price competitive than the broadband access, fixed voice or wireless markets, but perhaps not because the number of competitors is notably less.

The implication is that telecommunications market structure will always be relatively concentrated compared to industries where entry does not require substantial upfront capital costs.

The relationship between the number of firms and market power, where market power is defined as the ability of firms to price above marginal cost, implies that that some communications firms will now, and in the future, possess some degree of market power, Duvall and Ford say. Competition will not be "perfect," but rather workable.

Still, there is an important observation: tthe more intense is price competition the higher is industry concentration. The typical view of competition has price competition increasing with declines in industry concentration. In other words, the more firms in a market, the more “competitive” that market is.

The implication is that high concentration can be the result of intense price competition, rather than market defects.

In the summer of 2000, the proposed merger of MCI-WorldCom and Sprint was abandoned due to the

challenge of the merger by antitrust authorities. In retrospect, one can note that faulty conclusions were drawn from incomplete analysis. Market power in the long distance industry actually was illusory. Even strong industry concentration did not actually imply serious market power, as price competition, for example, was intense.

The obvious implication is that high levels of wireless industry concentration do not preclude or foreclose robust levels of competition. In fact, robust competition causes industry concentration. See http://www.phoenix-center.org/pcpp/PCPP10Final.pdf, for example.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

What Does "Effective Competition" Actually Look Like?

See http://www.phoenix-center.org/FordWirelessTestimonyMay2009%20Final.pdf, or http://www.phoenix-center.org/pcpp/PCPP12.pdf or www.phoenix-center.org/PolicyBulletin/PCPB11Final.doc.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Big Churn Potential in Wireless Business?

Nearly half of readers surveyed by Consumer Reports are unhappy with their cell phone service. Nearly two thirds had at least one major complaint about their cell phone carrier, with about 20 percent naming price as the chief irritant.

But here's the caveat. Most surveys taken over the last couple of decades suggested there was high dissatisfaction with cable TV service, for example. And, to be sure, consumers began to churn away as first satellite and now telco video alternatives are available. Until satellite became a viable option, though, high dissatisfaction was not accompanied by high churn.

The U.S. mobile industry, though, is among the most competitive in the world, so consumers do have lots of choices. So one wonders why more do not act as theory suggests they will, which is that unhappiness will lead them to try another provider. Maybe they are churning, and maybe their continued unhappiness means the new carriers aren't demonstrably and clear better than the carriers they left.

Apparently, neither better coverage nor new smartphones have been enough to change consumer satisfaction all that much, the report suggests, with the salient exception of the Apple iPhone. So will the latent unhappiness translate into higher churn? It's harder to decipher than one might initially think.

If consumers believe all the carriers have some gaps in coverage, have roughly similar or somewhat distinct retail offers, have adequate bandwidth and availability, and all of them will experience congestion during rush hour, consumers might not be extremely motivated to change providers, even if they are unhappy to some degree. The bad news for service providers might be that network quality and reputation have some effect, but not overwhelming effect on churn behavior.

But handsets are a huge motivator of change, it appears. About 38 percent of consumers who switched phones in the past two years did so to get the phone they wanted.

More than 27 percent went shopping with a specific phone in mind, in fact. About 98 percent of iPhone users said they would purchase the phone again. To point out the obvious, some people might be really happy about their handsets, and simply put up with their service providers.

But there is another way to look at matters. If half of consumers are unahppy to some degree, and that leads them to churn, what would one expect to see? At churn rates about 1.5 percent a month,. one would expect roughly 18 percent annual churn. That would roughly equate to 100 percent churn about every five years or so.

If one assumes only half of consumers are motivated to churn, existing churn rates easily could amount to churn of half the entire customer base about every two and a half years.

So maybe those unhappy consumers are in fact deserting their current providers. The reason they remain unhappy? One explanation could be that none of the providers they are trying are demonstrably better than the carriers they left. One often encounters consumers who say "we've tried them all, and all of them have some problems."

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

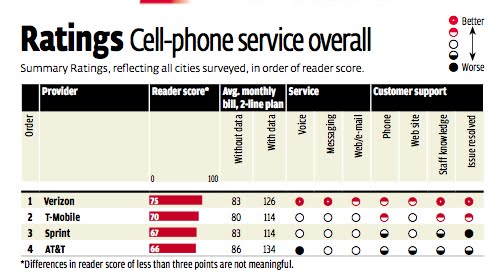

Verizon Ranked First in Consumer Reports’ "Best Wireless" Service Survey

Verizon received an overall score of 75, while T-Mobile USA got 70, Sprint got a score of 67 and AT&T got a score of 66. Consumer Reports itself says that differences of less than three points are not meaningful, so Sprint and AT&T essentially got the same score. And just three points separate T-Mobile from both Sprint and AT&T.

Another way of looking at matters is that while Verizon got scores noticeably different from the other three providers, and while T-Mobile USA was a clear number two, Sprint and AT&T were fairly close.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Monday, March 10, 2008

at&t to Raise Text Messaging Rates

For most of us, that means the buckets make even more sense. For light users, the move just shows how data services are becoming the revenue model for mobile services, with voice gradually declining in importance.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, March 6, 2008

T-Mobile Handles Churn

Though it doesn't appear T-Mobile USA will be changing its market share position in the near term, it appears to be doing a good job on the churn front.

It added 951,000 net new customers added in the fourth quarter of 2007, up from 901,000 in the fourth quarter of 2006. That's important because "net" adds are what one has left after deducting the customers who churned away in any given time period. The other data point is that, in its most-recent quarter, T-Mobile's churn dropped to 1.8 percent, down from 2.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2006.'

That is notable because T-Mobile has a large percentage of contracts that are of the one-year variey, not the the two-year contracts that increasingly are the norm in the postpaid segment of the market. It also is notable because there is some evidence T-Mobile customers are more active than customers of some of the other leading mobile carriers in investigating alternatives.

"T-Mobile customers are the most active in checking out competitive products and services," says Compete.com analyst Jeff Hull.

"This is partly because they are a younger, more active subscriber base, and partly because of the legacy of one-year contracts at T-Mobile," says Hull.

"If you look at an upstart like Helio, four percent of their site traffic is from existing T-Mobile customers, with two percent from both AT&T and Verizon Wireless, and Sprint/Nextel customers seemingly uninterested in checking out the MVNO."

T-Mobile customers also are over-represented at the Boost Mobile site, another youth oriented brand that is successfully attracting T-Mobile user interest. At the margin, and it might only be at the margin, there does seem to be a difference between customer bases at T-Mobile and Sprint or Nextel, for example.

Given the apparent high "shopping" and "comparison" behavior, the lower churn is an accomplishment.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Sprint Unlimited Plan: Unlimited Everything

Sprint Nextel now has responded with a new “Simply Everything” plan offering not just talk, not just unlimited texting, but unlimited Web surfing, email access, GPS navigation services, DirectConnect, GroupConnect, Sprint TV and Sprint music.

The $99.99 Simply Everything plan is available to customers on both Sprint's CDMA and iDEN networks, and goes way beyond T-Mobile's comparable plan that includes unlimited voice and texting.

Sprint has thrown in the kitchen sink.

Existing Sprint customers can switch to the Simply Everything plan without extending their current contract either by contacting Sprint customer service or by stopping by any participating Sprint retail location.

New line activations require a two-year agreement.

For families, Simply Everything includes an incremental $5 discount for each incremental line, up to five lines on the same bill. For example, two lines would amount to $194.98 ($99.99 + $94.99); a third line would cost an additional $89.99. This is in sharp contrast to the multi-line unlimited rates offered by some competitors. The Sprint plan offers significant savings the more lines a customer adds.

Observers were wondering whether Sprint would go nuclear. This move is more "nuclear" that offering an unlimited voice plan for lower prices than the now-industry-standard $100 a month. Sure, Sprint Nextel would have frightened a lot of people if it had gone with an $60, or even an $80 unlimited voice plan.

What it has done, at least for users who really like several of the enhanced features, is create a package so compelling lots of people are going to upgrade lower-priced plans to get them. Don't worry about some high-end voice plans being downgraded.

The big issue here is a potentially significant upgrade of lots of other plans, to get the huge palatte of upgraded features. It is the sort of move one would expect from Dan Hesse.

For users who don't mind the lack of subscriber information modules (SIMs), the plan offers more value than competing plans offered by T-Mobile, which bundles unlimited voice and text messaging. Both at&t Wireless and Verizon Wireless plans provide unlimited voice for $100 a month.

For users who simply want unlimited voice, Sprint will offer a $90 voice-only plan. So far, the feared price war has not broken out.

As for why unlimited plans might not damage wireless carrier revenue, take a look at what Sprint has been finding with its Boost mobile prepaid business. After launching unlimited plans, traditional prepaid growth slowed, but unlimited plans more than made up for the slower growth for the traditional plans.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Monday, February 11, 2008

Will Sprint Unleash Nukes?

So the issue is whether Sprint will "go nuclear," unleashing some sort of market-disrupting attack it expects its competitors will not want to match. Its a risky gambit, to be sure. AT&T completely changed the basic way mobile voice minutes of use are packaged when it launched "Digital One Rate."

But the tactic has not had long-term differentiating value because all the other major carriers simply shifted their packaging to match. So Sprint has to find a proposition that is startling and compelling to end users, but not appetizing for the more dominant providers to mimic quickly.

If the attempt is to "drive sales through the roof," nothing short of a disruptive move will work. Some suggest "unlimited calling" is one such tactic. Some smaller wireless providers such as Leap Wireless have prospered by offering unlimited local mobile calling. In so doing Leap and others have carved out a definable niche in the "wireline replacement," value calling and ethnic market segments.

There is some thinking that unlimited calling on at least a continental basis might be the same sort of market-shaking move, eliminating the "what is the right bucket size?" decision every consumer has to make, and transforming what is still a service sold on the basis of "scarcity" into a service whose premise is "abundance."

In some sense, Sprint CEO Dan Hesse actually has to hope that such an assault really would drive call volumes through the roof. Because if Sprint can do so, and its relatively generous spectrum will support the additional traffic, some other key competitors--especially Verizon and at&t--might not be able to quickly turn up additional bandwidth to match the offer.

And that's the other part of the equation. The offer must shake up user perceptions of value compared to price, as did Digital One Rate. But the offer must challenge Sprint's competitors enough that they will not immediately respond.

And at some level this is a nuclear strategy in an operational sense: if Sprint moves to provoke a non-linear increase in voice usage, can it handle the load? More important, can Sprint's competitors handle increases of the same magnitude if they decide to respond to the offer.

Likewise, there is the financial angle. If competitors match Sprint's offer, what is the level of damage they sustain in average revenue per minute of use, or average revenue per user? How does Sprint price and package so a direct competitive response is too painful to contemplate?

If Verizon and at&t can't match the offer without losing more than they gain, they won't match the offer. And if they won't, Sprint gains the distinctive positioning it seeks.

"Going nuclear" is going to be dangerous. But the only thing more dangerous at this point is thinking Sprint somehow can "creep" its way to success. The issue is where "unlimited calling" is, in itself, destabilizing enough to achieve what Sprint wants.

My sense is that it would not. Leap Wireless already offers a plan that is for most users a "national unlimited calling" plan, for about $50 a month. But there are other angles.

Unlimited texting or Web access might be more attractive. If Sprint really wants to disrupt the market, it can do something about texting plans.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Wednesday, February 6, 2008

at&t to Add 80 Cities to 3G Network

Most major metro areas already are covered, but you'd be surprised at the number of suburban communities even around the major markets that only have the slower EDGE data network. That's one reason, aside from battery life, that the Apple iPhone initially was available only in an EDGE network version.

By the end of the year, nearly 350 leading U.S. markets will be served by the 3G network, including all of the top 100 U.S. cities. The 3G initiative requires the building of more than 1,500 additional cell sites.

The at&t 3G network now delivers typical downlink speeds ranging between 600 and 1,400 kilobits per second, as well as uplink speeds ranging from 500 and 800 kilobits per second, though the network is not yet completely equipped for the higher upstream capacity at all sites.

People often underestimate how long it takes for a national network to be created, even if it is a wireless network. Back in the regulated days of telecom, for example, a sizable telecom company would expect to upgrade or replace only about 10 percent of total plant in any single year.

So access plant changed slowest, though switch replacements could occur more quickly. And it isn't just "physical" networks that have to be built. A large carrier might operate 50 to 100 "logical" networks, as each separate service often required its own hardware, software, provisioning and billing systems.

Likewise, consider that Verizon Wireless has invested $300 million in 2007 to enhance its networks in Maryland, Washington, D.C., and Virginia alone, largely related to broadband upgrades, spending $6.5 billion investment nationwide.

"Reliable wireless networks are not built overnight," says Tami Erwin, Verizon Wireless regional president.

From an at&t Wireless perspective, it will take a year to light 80 communities, using 1,500 towers, to create a 3G network in those areas. And there will be more work next year.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, January 31, 2008

at&t Wireless Outage

In case you are having trouble sending and receiving email on your at&t Wireless smart phone, or are unable to get connected using your data card, there is a wireless network outage affecting at&t Wireless users in the Midwest and Southeast.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

Wireless Open Access Watch

With a change of presidential administration, and the high possibility that the White House will be occupied by a Democrat, all bets are off where it comes to the composition, leadership and therefore direction of Federal Communications Commission policy. But it is fair to say that a more heavily regulated approach is likely if Democrats win the White House. Incumbent tier one U.S. telcos won't like that. For other reasons, cable industry leaders will be happy as well. Competitive providers might well think their chances improve as well.

So it might be all that significant that Commissioner Michael Copps, a Democratic member of the FCC, seems to want to give incumbent wireless providers a bit of time to make good on their recent pledges to move towards more open networks, allowing any devices or applications compliant with their networks to be used.

That's an obvious counterweight to any thinking by an eventual owner of a new national broadband network that construction and activation of that similarly open network should be built as slowly as legally possible, essentially "warehousing" spectrum as long as possible. The motivation obviously is to extend the life of current revenue models as long as possible.

Pressure to keep those promises about openness on the Verizon and at&t Wireless networks will remain high if Democrats win the White House. In fact, pressure to open up wireless networks more than before is likely unstoppable if Republicans retain the White House as well. The 700-MHz auction rules about openness were pushed through by a Republican FCC chairman and the market seems to be shifting inevitably in the direction of open devices because of the market force exerted by the Apple iPhone and Google, in any case.

Dominant wireless carriers really would prefer not to deal with more openness. But it appears they no longer have a choice. That's going to be good for some new handset providers, application developers and end users, both consumer and business.Bidden or unbidden, openness is coming.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Friday, November 16, 2007

Google Will Bid on 700 MHz Spectrum!

Google is preparing to bid at least $4.6 billion for wireless spectrum to be bought at the Federal Communications Commission's January auction, the Wall Street Journal reported says. The company is planning to bid without partners, a move some of us would not have predicted.

The company is beta testing a wireless solution in preparation for running a full-scale national mobile network. Obviously, Google as a mobile network services provider would be highly disruptive to the existing legacy carrier business models, given the likelihood Google would emerge fairly quickly as a packaging, pricing and

network functionality innovator.

One simply has to point back to packaging and pricing innovation by just one carrier--AT&T--to illustrate the fact that a significant new pricing pattern, in this case the concept of a bucket of minutes for a flat fee, can cause an entire industry to react.

A bid obviously would vastly complicate Google's other efforts to gain favorable placement of its software on all sorts of devices compatible with all sorts of carrier networks. But Google probably wins even if it loses. By creating a "bid" poker chip, it can wring concessions out of recalcitrant carriers who might be wary of giving Google more play.

And there are very real costs to be borne by the likes of Verizon and at&t if Google enters the bidding contest. It is not simply the threat that Google wins. If Google bids, the final price paid by the auction winner, whether at&t or Verizon, will be higher than if Google had not been a contestant.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

How Much Do Tariffs Affect Inflation?

Today’s political discussions can be frustrating and unhelpful, in large part because people disagree about what the “facts” of any subject ...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

Financial analysts typically express concern when any firm’s customer base is too concentrated. Consider that, In 2024, CoreWeave’s top two ...