One reason why mobile marketing wars become so intense is that markets often are quite stable. In other words, in mature markets, customers simply do not change service providers all that often.

According to a recent study by Ofcom, the U.K. communications regulator, just eight percent of adults fixed network voice customers in the last 12 months. About nine percent of broadband access customers switched in the last year.

Just six percent of mobile customers switched providers in the last 12 months, while just five percent switched their subscription TV provider over the same time frame.

What that means, for any mobile service provider in a mature market is that only about one half of one percent of current customers will choose another provider in any given month. So all marketing efforts by any service provider, in any month, are aimed at inducing just one half of one percent of customers to switch.

That is by any accounting an expensive proposition.

Likewise, Parks Associates consumer data show that almost 50 percent of U.S. mobile phone service customers did not change providers over the last 10 years. In other words, fully half the customer base virtually never changes providers, meaning that all switching behavior is concentrated on just half the total subscriber base.

According to Parks Associates, about 25 percent of respondents changed service providers only once in 10 years.

Just 13 percent of respondents switched providers three times or more (about once every three years or so).

Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility have the most stable customer bases. About 62 percent of Verizon and 56 percent of AT&T customers have been with their present carrier for more than five years.

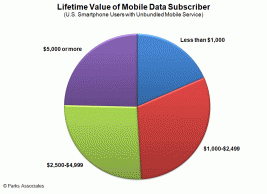

Parks Associates estimates that about 35 percent of AT&T customers are worth $5,000 (lifetime value of the account) or more, the highest among the four national carriers. T-Mobile US, by way of comparison, has about 21 percent in that category.

Of course, the lifetime value of an account varies wildly. If half of all accounts churn almost never over a decade, and if those accounts are multi-user accounts, lifetime value could easily reach $48,000 over a 10-year period ($400 a month, for 10 years).

That is why churn management (for the incumbent), or churn encouragement (for the attacker), matters so much. Some acquired accounts could be lucrative far beyond the $1,000 to $3,600 “lifetime” value of a single-user account.

Far more lucrative are shared accounts (“family or framily”), which represent multiple users, devices and lines, and therefore higher account value. Dislodging a single such account, under some circumstances, could literally be a $48,000 win, over 10 years.

And it is even possible that churn rates could decline, longer term, in Europe and the United States, though a reasonable observer would expect a temporary increase in churn rates as marketing wars heat up.

The percentage of mobile subscribers who are planning to switch service providers decreased from 14 percent annually in 2009 to nine percent annually in 2010, for example, Analysys Mason analysts say.

Subscriber Churn Intentions

Source: Analysys Mason, 2011 (2009 data not available for Spain and the USA)

The mobile churn rate in some developed markets stood at about 30 percent as recently as 2009, Analysys Mason says.

And though one might not want to make too much of it, a study sponsored by Ofcom, the U.K. communications regulator and conducted by Ipsos Media CT suggests females are less likely to churn, and males more likely to churn.

The U.S. mobile services marketing war will be intense, in part because it is so difficult to dislodge even a single customer, and will be particularly important for multi-user accounts that historically have been resistant to churn.