Tine Warner Cable has accepted a $45 billion acquisition offer from Comcast, after rejecting earlier offers from Charter Communications, and presenting the Federal Communications Commission with another test of U.S. service provider market power.

Tine Warner Cable has accepted a $45 billion acquisition offer from Comcast, after rejecting earlier offers from Charter Communications, and presenting the Federal Communications Commission with another test of U.S. service provider market power.

The new twist is that the merger might not be most significant for its impact on video markets, though that will be an issue, but for the impact on high speed access markets. And though it is formally unrelated, the potential Sprint acquisition of T-Mobile US could be affected as well, if Sprint concludes either that the Comcast purchase of Time Warner Cable is likely to fail, or that it is likely to be approved.

Though regulators will look at the impact on relationships between video content owners and distributors, the tougher questions are likely to revolve around the impact on high speed access markets, even though there is almost no overlap of Comcast and Time Warner Cable operating areas.

Few would question the centrality of broadband access for fixed network service providers. And few would argue with the notion that cable tends in most markets to be the top provider, in terms of market share.

On the other hand, recent experience suggests that the DoJ would be willing to approve a Comcast acquisition, after deal adjustments.

In 2013, the DoJ sued to block major deals in the beer and airline industries, but both mergers were eventually allowed after concessions. Some think that is the likely outcome for the Comcast acquisition of Time Warner Cable as well.

The unknown, for Sprint, is whether that also would work for its desired acquisition of T-Mobile US.

Ironically, the amount of market share lost by cable operators, collectively, over the last decade to satellite and now telco competitors will make the Comcast deal easier than it would have been in the past. By 2012, the U.S. cable industry market share had dipped below 60 percent.

Without that loss of share, Comcast already would have well exceeded an informal rule that no provider can serve more than about 30 percent of U.S. customers without triggering antitrust review.

A formal Federal Communications Commission rule to that effect had been in effect until 2001, when the FCC rule was declared unlawful. The FCC adopted a new version of the rule in 2007, but that version again was struck down by an appeals court in 2009.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit said the FCC "failed to demonstrate that allowing a cable operator to serve more than 30 percent of all cable subscribers would threaten to reduce either competition or diversity.”

Still, most executives voluntarily prefer not to push the informal limit, so Comcast likely will shed enough subscribers to stay at or below the 30 percent limit.

Time Warner Cable had been the second=largest U.S. cable operator; Comcast clearly the largest. Comcast has about 21.6 million subscribers, while Time Warner Cable has about 11.4 million customers, for a combined total of about 33 million, out of 92.5 million U.S. video subscription customers.

By that reckoning, where the market is defined as all video subscription customers, instead of just “cable customers,” Comcast would have 34 percent market share. That means Comcast will have incentives to divest up to four percent of the newly-acquired customers, to stay at 30 percent share.

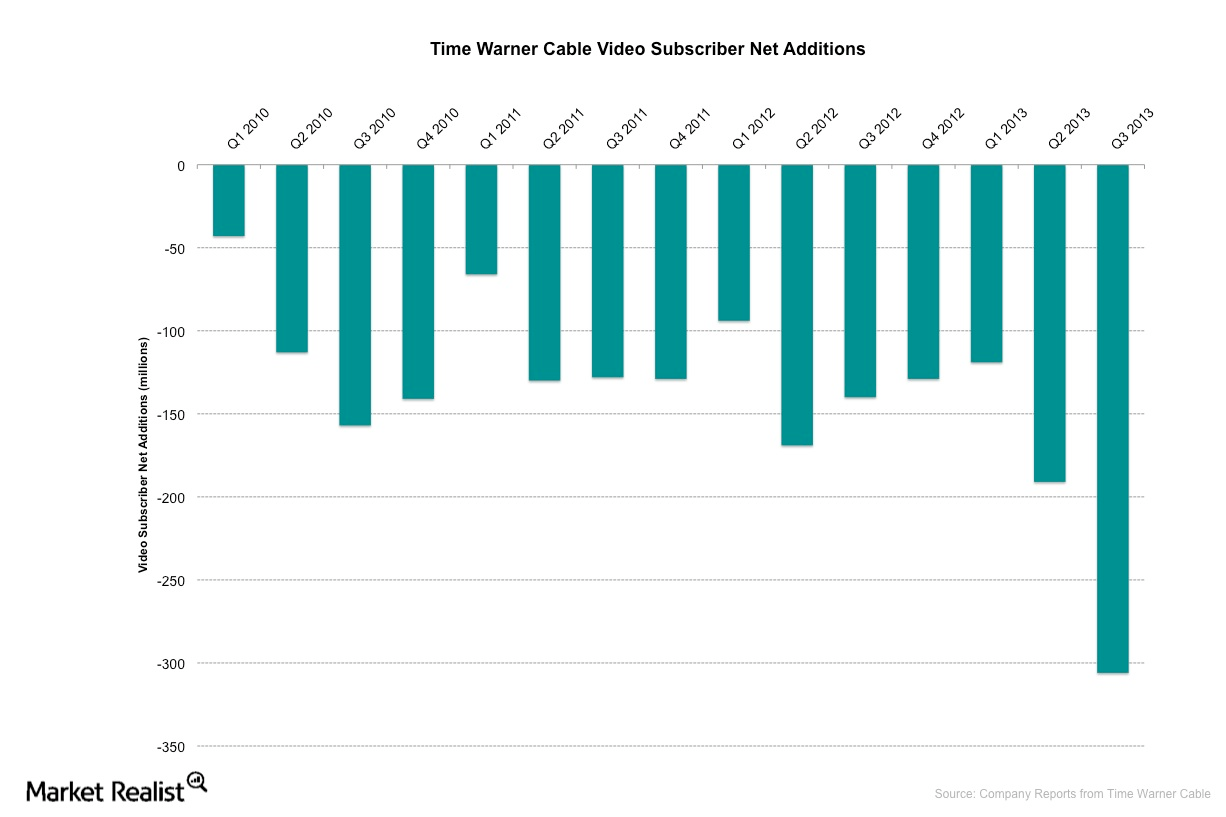

Since the beginning of 2010, Time Warner Cable has has been losing customers, at least 2.05 million video subscribers, or approximately 16 percent of its subscriber base.

That is one good reason for the recent interest in an acquisition by both Comcast and Charter Communications. An acquirer would assume it can do better.

That is one good reason for the recent interest in an acquisition by both Comcast and Charter Communications. An acquirer would assume it can do better.

It is possible the deal could falter, especially if Comcast equity price dips significantly. It also is possible there could be adjustments if Time Warner Cable’s equity price were to rise substantially. And Charter could raise its bid, though most seem to think that is unlikely.

Instead, Charter likely would be offered a chance to buy the customers Comcast would shed.

U.S. merger law is governed by the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act, under which the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice evaluate mergers for their impact on fair competition. By current law, all mergers that are valued above $66 million must receive approval to go forward. But deals smaller than that can be reviewed whenever the Department of Justice believes a deal would affect competition in an industry negatively.

The Comcast acquisition also must be reviewed by the Federal Communications Commission as well.

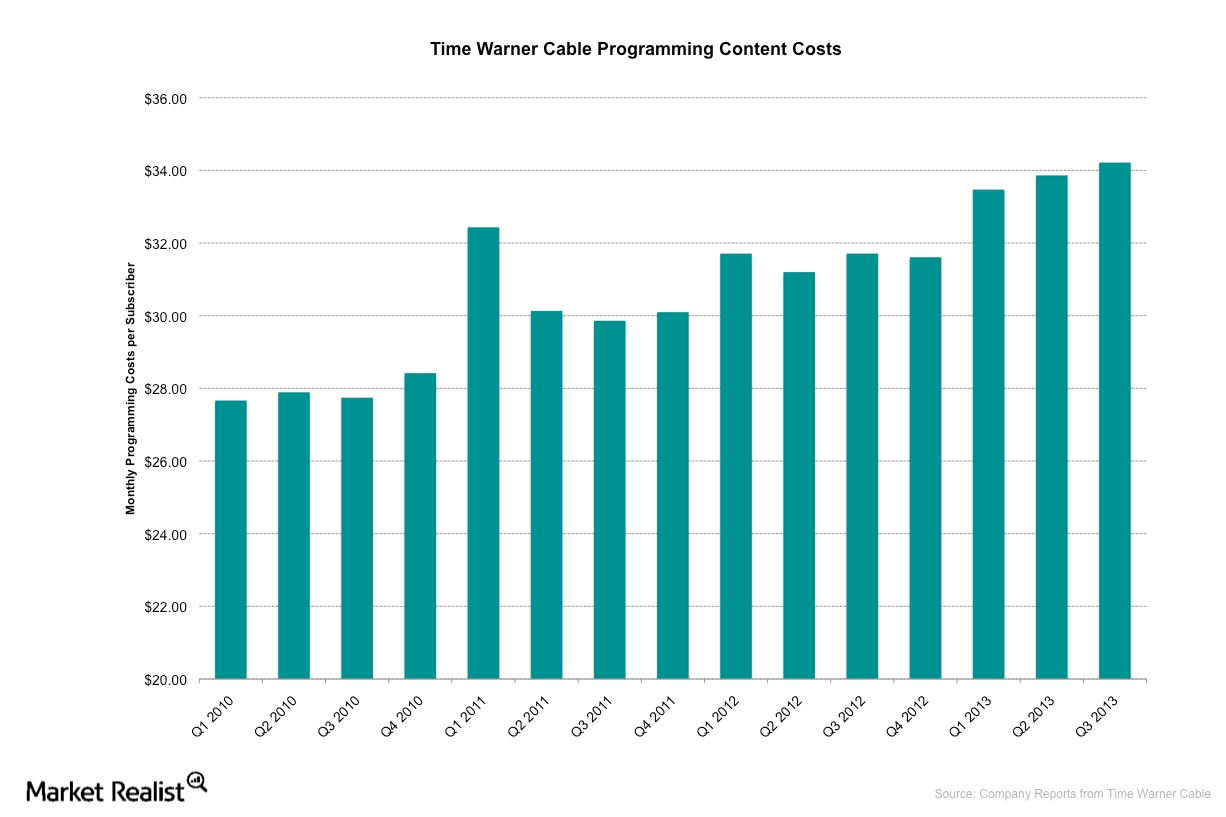

Merger activity can heat up in a particular industry for various reasons, such as poor overall growth prospects for the industry, underperformance by one player within the industry, or opportunities to grow more profitability through synergies. Consolidation expectations within the cable TV industry have begun to heat up due to all three of these drivers.