This is funny!

Monday, May 15, 2017

Hilarious Skit on Amazon Echo "Silver"

This is funny!

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Has Video Cord Cutting Finally Reached an Inflection Point?

This is probably a good example of what an inflection point (if accurate) looks like: more than half of “cord cutters cancelled their legacy pay-TV service in the two calendar years of 2015 and 2016,” according to The Diffusion Group (TDG).

In other words, the rate of change--assuming the data is correct--itself changed in 2016. In 2016, the linear video abandonment rate hit about two percent, much higher than had been the case over the last decade or so, where annual net losses have been in the “far less than one percent” range for most of the last five years. So a jump to as much as a two-percent abandonment rate in a single year would, if continued, represent an inflection point.

Inflection points are important, as they signify the “turning point” where an existing trend changes its rate, and goes exponential.

About a third of all respondents reporting they had abandoned linear video services had done so in a single year: 2016, an indication that the long-expected inflection point for linear video has been reached, and that change now will rapidly accelerate, if the TDG consumer response data is accurate.

The issue is that the self-reported behavior is at significant variance (an order of magnitude, 10 times) with other data.

Still, assume the high and low estimates of service abandonment are directionally correct, and that even the low estimate represents a dramatic rate of change difference that is sustained over the next few years and beyond.

If so, then cord cutting not only has passed its peak of adoption, but now will decline much faster than has been the case over the last decade. Much depends on whether respondents are accurately reporting their behavior. There is some evidence they are not.

It is true that the rate of linear video subscriptions is increasing, but still at relatively low rates.

One has to be careful, though. It appears to have generally happened that sales of voice subscriptions by legacy telcos has fallen as precipitously as projected in the past.

What also has to be noted is that there has been offsetting product substitution (mobile for fixed) as well as supplier market share changes (share shift to alternate suppliers such as cable TV providers).

To be sure, few telcos actually report that voice line sales are as low as 18 percent of locations passed, though some have predicted losses would be that large. Instead, most legacy telcos say slightly fewer than half of homes passed actually buy a voice service.

The point is that, in the U.S. market, an inflection point for fixed network voice subscriptions was reached about 2000 or 2001, marking not simply the point where growth rates changed in terms of magnitude, but also in direction (positive to negative).

The same inflection point can be seen in global use of text messaging, where over the top alternatives hit an inflection point around 2003 to 2006, for example.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Comcast Has Done Best "Moving Up the Stack"

There’s a difference between aspiration and reality, but Comcast arguably comes as close any U.S. communications provider in moving from “mostly aspiration” to “substantial reality” in the area of becoming a firm generating revenues from content and apps, instead of "access" or "distribution" services.

Among major U.S. telecom firms, AT&T will follow, establishing a logical strategy for revenue source diversification in the business services markets. driven most likely by internet of things businesses.

That should eventually become more clear as internet of things services and apps start to become a substantial generator of revenues.

Among major U.S. telecom firms, AT&T will follow, establishing a logical strategy for revenue source diversification in the business services markets. driven most likely by internet of things businesses.

"We don't see ourselves as a cable company ," said Matt Strauss, Comcast EVP.. "We see ourselves as a technology and communication-entertainment company, much more in the consideration set of Apple and Google than more of the traditional cable and satellite providers."

Reasonable people will disagree about the extent to which that is a reality. Measured by revenue, Comcast still remains a firm that earns much of its revenue in the access business. But it started much earlier, and is far ahead, of other firms such as AT&T and Verizon. Sprint and T-Mobile US have not really tried.

In 2008, 59 percent of Comcast’s revenue came from linear video service. In the second quarter of 2016, just 29 percent of Comcast’s revenue is derived from video services. NBCU (the content and entertainment producer) is now the largest component, contributing 37 percent of total revenue.

Presumably, most telcos globally would be very happy to say that 37 percent of total revenue came from applications, services and sources not directly related to the access business (data, voice, video, text messaging, mobile subscriptions). It also might be said that about half of Comcast revenue still is earned from the cable networks business, however.

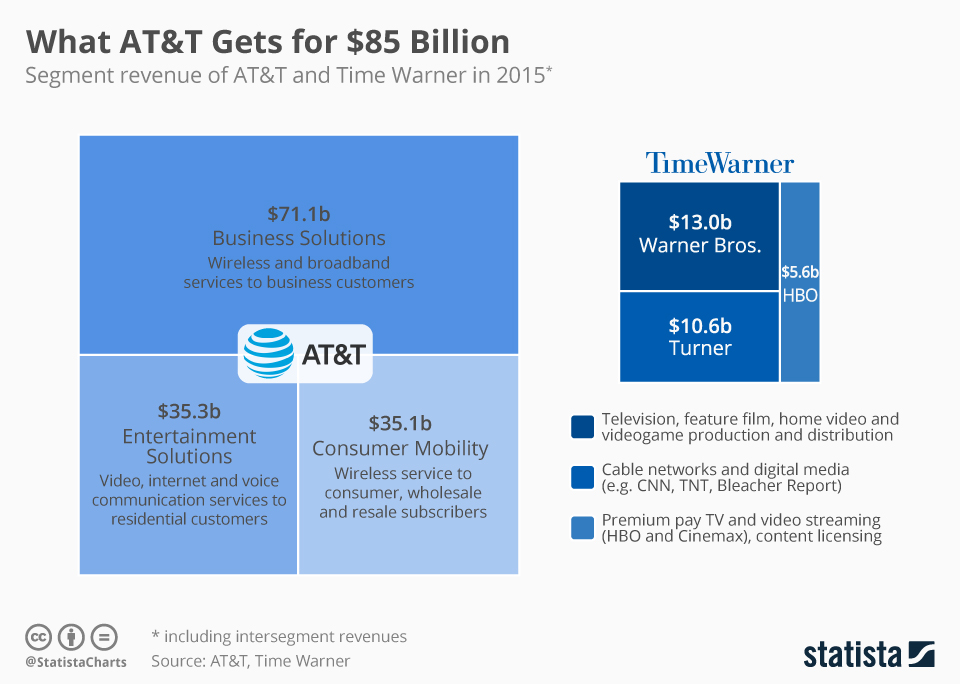

AT&T will be first among the U.S. telcos to revamp its revenue sources in a similar way. Assuming AT&T’s acquisition is approved, AT&T might earn about $142 billion in total annual revenue. After the acquisition, AT&T might earn about 17 percent of total revenue from studios and programming networks (content), not distribution of any sort.

More important is the overall evolution of revenue sources over time. Call it “moving up the stack” or “up the value chain” or any other similar trend: the eventual evolution of at least some tier-one communications (access providers) firms is towards a mix of sources including access services.

That should eventually become more clear as internet of things services and apps start to become a substantial generator of revenues.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Friday, May 12, 2017

5G: Lots of Moving Parts, Significant Business Model Uncertainty

“Lots of moving parts” is an accurate way to describe the range of 5G building blocks. In the past, mobile network generations mostly have been about new air interfaces. But 5G is the first new platform that requires core network changes, is built to support both human and machine users at scale, use cases of varying bandwidths and core requirements, and the first to use frequencies that have historically been unusable commercially.

A presentation by Dan Warren, Samsung head of 5G research, aptly illustrates those issues. The coming 5G networks will require new radio access network architectures and rely on a virtualized core network.

Among the biggest uncertainties is whether 5G will lead to significant incremental growth of revenue sources from non-human use cases. The higher capital investment also is an issue, if upside from human use cases is rather limited and new revenues from internet of things is uncertain.

It is possible that new access revenue from IoT will be lower than many expect. Much of the revenue upside lies in the IoT platforms, services and apps, but only service providers with scale will be able to invest in such parts of the ecosystems.

Moving up the stack is a universally-acknowledged way to capture more value, more revenue and profit from the internet and mobile ecosystems. But that is not easy.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Spectrum Prices Have to Fall in 5G Era

Spectrum prices are going to quite important in the 5G era, for fundamental reasons related to changing mobile business models. Higher network investment and limited revenue upside are among the key issues.

The next generation of 5G networks will cost more than 3G and 4G networks did, in part because they will use small cells. That will have dramatic cost implications for the simple reason that shrinking cell site radius by 50 percent quadruples the number of cells required.

That reduction of cell radius has been going on for some time, as higher-frequency signals have been put into use.

“One study found that the cost (capex) of coverage at 3500 MHz using presently available technologies (not 5G) was roughly 6.7 times as great as the cost of coverage at 700 MHz,” says Bruegel contributor Scott Marcus. That cost differential comes primarily from the greater number of cell sites required at higher frequencies.

At the same time, revenue upside is more questionable than has been the case in the past. One reason is that services humans will pay for (to use their smartphones and other personal devices) are more limited, as every major revenue source (voice, texting, internet access) is saturated, reaching saturation or going to reach saturation.

That means the higher capital investment is not clearly matched by proven incremental revenue upside that will pay for the new networks.

In many advanced countries, subscriber penetration is well above 100 percent and average revenue per account is not increasing.

Against this background, the ability of operators to monetize the growth in demand for mobile data, for example through fixed-mobile convergence or new value-added services linked to the Internet of Things, is uncertain.

Also, big changes in spectrum supply are coming, for a combination of reasons including a shift to small cell architectures, huge amounts of new spectrum in the millimeter regions, spectrum sharing and additional unlicensed spectrum, better radios and even the ability to create larger channels, which itself increases effective utilization of any available spectrum.

Normal economic realities suggest that vastly increased supply of a desired good should lead to lower prices. That suggests spectrum prices must decrease.

High spectrum costs always have been a barrier to market entry in the mobile industry. Indeed, some would argue that mobile business models are built on spectrum scarcity.

The corollary is that releasing more spectrum, at lower prices, spurs competition and innovation.

A study by NERA Economic Consulting, sponsored by the GSMA, argues that high spectrum prices have lead to lower-quality networks, reduced take-up of mobile data services, reduced incentives for investment, higher consumer prices and lost consumer welfare with a purchasing power of US$250 billion across a group of countries where spectrum was priced above the global median.

“Where governments adopt policies that extract excessive financial value from the mobile sector in the form of high fees for spectrum, a significant share of this burden is passed onto customers through higher prices for mobile and lower quality data services,” NERA says.

“In summary, the current outlook is for reduced spectrum scarcity but uncertain scope for operators to generate revenues from mobile networks,” NERA notes. “This implies that prices paid for spectrum should fall, especially as future releases are increasingly focused on higher frequency bands.”

“Countries that try to resist this trend, either by restricting spectrum availability or overpricing newly released spectrum, are likely to see large amounts of spectrum go unallocated,” NERA warns.

source: GSMA

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Will CBRS Be the New Wi-Fi, a New Real Estate Play or Wholesale Capacity Play?

It is hard to know, in advance, how important a new block of 150 MHz of mid-band mobile spectrum can be, and in which deployment models, especially since the rules on indoor and outdoor use are so different.

The Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) is a prime example. CBRS creates a three-tier access system where primary licensees are protected, but licensed secondary users have access when the primary user has fallow spectrum. Also, tertiary users can have "best effort" access, on the Wi-Fi model, when neither primary nor secondary users need all the available spectrum.

In principle, CBRS also includes different licensing rules for outdoor and indoor use. Indoors, a property owner can create a private Long Term Evolution (LTE) 4G network. In principle, a big enterprise could essentially create a private LTE network to support better indoor signal reception.

Of course, the issue is that the value of doing so is highest if if multiple commercial LTE networks (AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile US and Sprint are supported, since that ensures that any customer, on any network (retail or wholesale), can use the network. How much capital any enterprise wants to sink into that sort of infrastructure is the issue.

One obvious monetization method is to create a wholesale infrastructure that is open to use by any of those network services providers. In other words, in principle, a real estate opportunity essentially is created. As always, that also means there is room for specialized real estate developers to enter the market.

In other words, eventually, as commercial aggregators of commercial Wi-Fi hotspot have developed, so in principle a new type of indoor mobile infrastructure could develop (think Boingo), with the business model being selling access rights to mobile operators.

The other logical platform is to use outdoor rights to build a "traditional" mobile service, using the secondary licensing method.

Possible, though more complicated, are other business models based on tenant communications, though that always has been a fragmented and difficult undertaking.

It's new terrain. Never before has so much spectrum been made available on a "shared" basis, where new licensed users can be added to a band where primary licensees retain their rights to primary use.

Spectrum traditionally has been a very scarce resource. Indeed, whole business models and industries have been built on exclusive use to spectrum. In the analog world, sharing was difficult to impossible. In today's world, it is comparatively easy. Not always easy, but doable.

Spectrum clearing and reallocation used to be the only way to shift capacity from one set of licensed users to others. It always is expensive and time-consuming.

Spectrum sharing now allows more-effective use of existing licensed spectrum that is underused, not by moving licensees, but allowing new users access on a shared basis.

Neville Meijers, VP Business Development, and Patrik Lundqvist, Director Technical Marketing, Qualcomm Technologies, talk about use models for CBRS.

The Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) is a prime example. CBRS creates a three-tier access system where primary licensees are protected, but licensed secondary users have access when the primary user has fallow spectrum. Also, tertiary users can have "best effort" access, on the Wi-Fi model, when neither primary nor secondary users need all the available spectrum.

In principle, CBRS also includes different licensing rules for outdoor and indoor use. Indoors, a property owner can create a private Long Term Evolution (LTE) 4G network. In principle, a big enterprise could essentially create a private LTE network to support better indoor signal reception.

Of course, the issue is that the value of doing so is highest if if multiple commercial LTE networks (AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile US and Sprint are supported, since that ensures that any customer, on any network (retail or wholesale), can use the network. How much capital any enterprise wants to sink into that sort of infrastructure is the issue.

One obvious monetization method is to create a wholesale infrastructure that is open to use by any of those network services providers. In other words, in principle, a real estate opportunity essentially is created. As always, that also means there is room for specialized real estate developers to enter the market.

In other words, eventually, as commercial aggregators of commercial Wi-Fi hotspot have developed, so in principle a new type of indoor mobile infrastructure could develop (think Boingo), with the business model being selling access rights to mobile operators.

The other logical platform is to use outdoor rights to build a "traditional" mobile service, using the secondary licensing method.

Possible, though more complicated, are other business models based on tenant communications, though that always has been a fragmented and difficult undertaking.

It's new terrain. Never before has so much spectrum been made available on a "shared" basis, where new licensed users can be added to a band where primary licensees retain their rights to primary use.

Spectrum traditionally has been a very scarce resource. Indeed, whole business models and industries have been built on exclusive use to spectrum. In the analog world, sharing was difficult to impossible. In today's world, it is comparatively easy. Not always easy, but doable.

Spectrum clearing and reallocation used to be the only way to shift capacity from one set of licensed users to others. It always is expensive and time-consuming.

Spectrum sharing now allows more-effective use of existing licensed spectrum that is underused, not by moving licensees, but allowing new users access on a shared basis.

Neville Meijers, VP Business Development, and Patrik Lundqvist, Director Technical Marketing, Qualcomm Technologies, talk about use models for CBRS.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

AI Revenue to Reach $60 Billion by 2025

Revenue generated from the direct and indirect application of artificial intelligence (AI) software will grow from $1.4 billion in 2016 to $59.8 billion by 2025, according to researchers at Tractica.

Out of the top 10 use cases, 40 percent are related to big data and 60 percent are related to computer vision and natural language processing. The former has use cases such as customizing content feeds for consumers. The latter has application for user interaction with devices (language processing) and process automation (automated vehicles).

Deep learning remains the largest technology category overall, although machine learning has been changed to represent a larger portion of the overall mix, Tractica says.

Deep learning applies some of the same machine learning principles like clustering and classification onto neural networks (computing networks that process like humans do).

Machine learning (the ability of machines to learn from their experiences without explicit programming) is described by Tractica as “classical machine learning techniques like support vector machines, regression, classification, and clustering that do not use neural networks.”

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Declining Robotics Costs Drive Substitution for Human Labor

Robots, as a form of embodied artificial intelligence, are declining in cost so much that it is virtually inevitable they will become functi...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...