Ecosystem might be the term that is replacing platform as a broad description of business strategy for would-be market leaders. And it is likely to be even harder to achieve, for most firms, in most industries.

One study found that attempted platform failure rates were about 80 percent, about the same failure rate we see in information technology projects, firm startups and most change initiatives.

The difference goes beyond nomenclature, even if many use the terms essentially interchangeably.

Ecosystems can be thought of as “networks of networks.” Think of the internet. Does it have a single active organizer? Is it under any single entity’s control? Closer to home, think of the global telecom network, which is a network of networks.

Travel is an industry that might be thought of as an ecosystem, but it is not centrally managed. A platform, on the other hand, always has an organizer or orchestrator.

Platforms, on the other hand, can be created by a single entity, though not without the participation of many other full-ecosystem participants. Uber and Lyft can create platforms for ridesharing, but not lodging, which can be organized by firms such as Airbnb.

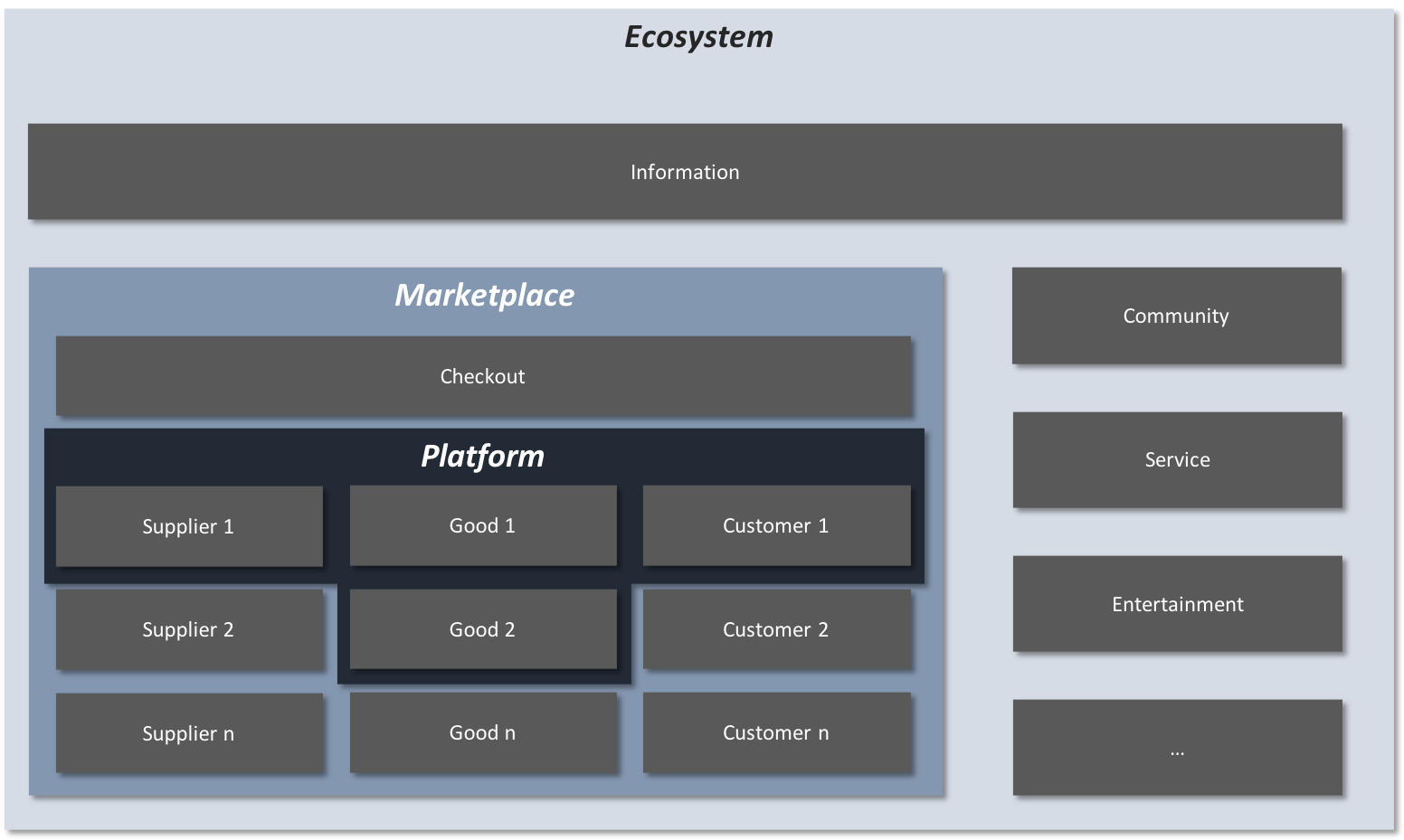

Some might argue that the platform is the tool or foundation other products, supplied by third parties, build upon. In that taxonomy, the ecosystem would refer to the totality of products and relationships built on the platform.

That makes less sense to me than than a taxonomy based on whether there is an active orchestrator or aggregator. A biological ecosystem has no human or mechanical organizer. It develops, but is not “planned” or “managed.” A platform always is managed, with admission and operating protocols.

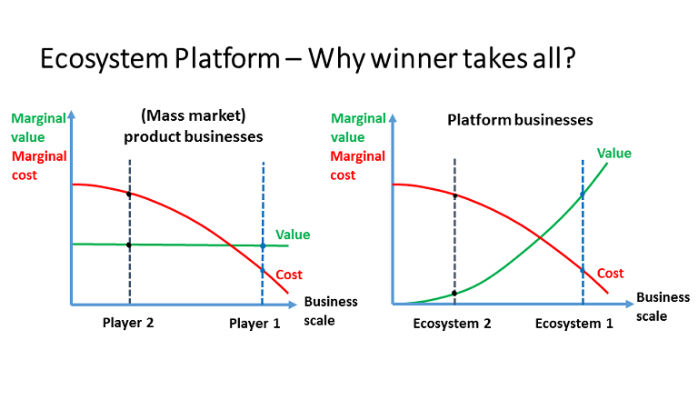

Network effects are key, in either case. A network effect essentially means that value grows as the number of users grows. It is different from mere scaling. More scale leads to lower unit costs, but no increase in value.

source: Linkedstarsblog

A network effect increases value as the number of users increases.

One might generalize and argue that ecosystems are about increased end user value, while platforms are more directly about firm value and revenue. The total value of the Apple iPhone ecosystem for end users exceeds the value reaped by any single supplier participant.

That noted, even when most of the ecosystem revenue is earned by third party participants, the orchestrator of the platform still gains value, if not always huge amounts of direct revenue, as when the orchestrator profits by transaction fees, commissions, licenses, support services, advertising, referrals or some other revenue model.

An ecosystem is unitary; a platform can exist as one of many. Amazon or Alibaba can create platforms for some retail products, but arguably not all, while existing within the broad “retail” ecosystem.

An ecosystem is a community of interacting entities, some say. The members of the ecosystem can be organizations, businesses and individuals, all creating value for one another in some way; mostly by producing or consuming goods and services.

A platform is the way a particular community or ecosystem is organized to interact with one another and to create value. A platform typically is focused on bringing part of the “ecosystem” together and reducing friction for interactions to take place.

source: Kilian Veer

Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Google, Apple, Amazon and Facebook might be considered platforms that organize some of the value created by the internet. But the internet ecosystem is too big to be anything but a collection of value created by various platforms.

What is more certain is that a business model based on building an ecosystem or platform is not the same as building a traditional pipe business model where a firm creates and sells a product or products that have a specific role in a value chain.

By “pipe” is meant not just “communications services” but any product created and sold to customers. Most products and most firms historically use a “pipe” business model, in that sense.

Indeed, there is a key difference between selling in an ecosystem and organizing the ecosystem. Amazon and Alibaba create and organize their platforms and ecosystems, if you believe both are ecosystems. We can say with certainty that both are platforms.

It might be debatable in some quarters whether those firms--or others such as eBay--actually have created ecosystems.

Every other firm buying or selling on the or to the platform is part of the ecosystem.

Every successful platform or ecosystem produces value in excess of what is contributed by any single firm. That is generally not true for a pipeline product, where value is fixed: it works, or does not; the specific problem is fixed; a specific capability is gained.

The value of the entire internet exceeds the specific value contributed by each point solution.

The role of any business or entity within a value chain is determined when it asks who are our customers? A chip foundry has chip suppliers as customers; chip suppliers have device manufacturers as customers; device suppliers have consumer or business users as customers; applications have users (subscription models) or advertisers as customers.

Platforms can take aggregator or orchestration roles within an ecosystem. Platforms can create the marketplace or transaction venue (aggregating suppliers and buyers) or orchestrate the creation and operation of platforms.

Platform business models and ecosystems, broadly speaking, seem destined to play a greater role in digitally-enabled industries. But most firms will never become platforms.