The actual impact of the 2021 infrastructure bill passed by the Congress will hinge on the rules governing disbursement of the funds. But the funds are sure to decrease the cost of adding new infrastructure and increase demand as well.

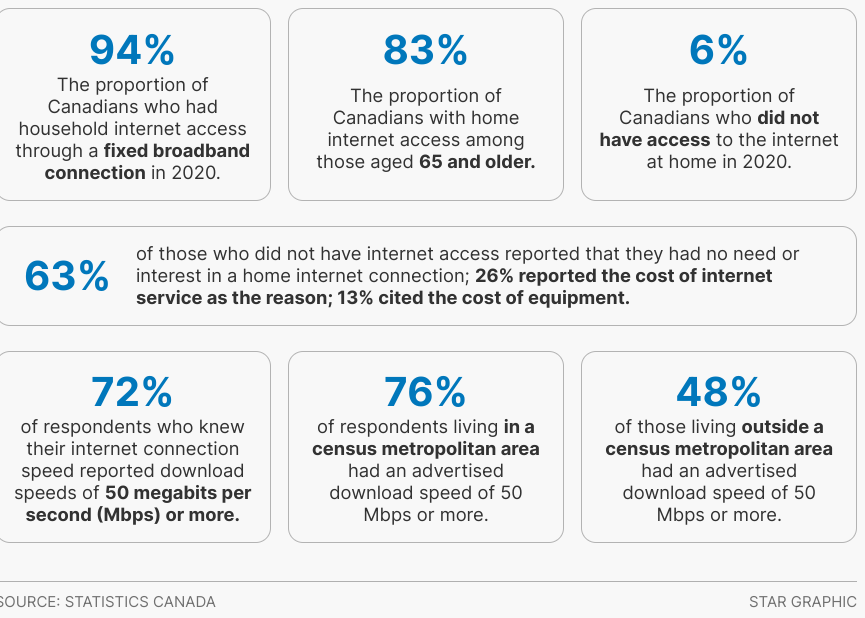

It also is worthwhile noting that not every household “does not have access” to broadband for reasons of supply. In Canada, for example, six percent of homes do not buy fixed network broadband. Some 63 percent report they do not wish to buy. Some 39 percent claimed they could buy, but that cost was the issue.

Note the non-existent percentage of “non-buyers” who say they “cannot buy” because the service is not available. In the U.S. market, it often is estimated that about 1.5 percent to two percent of homes literally do not have any fixed network service available to them.

The point is that most buyers unable to use “broadband” (defined as a minimum of 25 Mbps) actually do have internet access from one or more providers, though speeds are not what most of us prefer.

That is important as we look at the potential impact of new U.S. federal government support for broadband.

source: Statistics Canada

Though money can be spent on digital literacy, equipment support or other training, most observers are likely waiting to see what impact can be made on quality of service. Connecting the “unconnected” also is important, for the last one to two percent of homes.

But quality of service is the bigger issue for most.

So how might the money could affect a single state, such as Hawaii. Assume total spending is about $300 million. What could that do? Much depends on the mix of demand and supply incentives, and none of that is clear yet.

Assume, for the sake of argument, half is used to stimulate demand, and half is used to stimulate supply. At a subsidy rate of $30 per month, the fund means $360 in annual benefits for eligible households. That arguably means 416,667 annual subsidy accounts. Over a decade, that would mean 41,667 households per year could save $360 in access fees.

That might actually exceed actual demand.

Assume10 percent of people cannot buy internet access. Some might not buy because there are no facilities or cost is deemed too high. Those are easier problems to solve than gaining adoption by households that see no value to computers or internet access, or who see mobile broadband as a reasonable substitute product.

According to Broadband Hui, some 55,000 households in Hawai‘i (nearly 12 percent) do not buy internet access services. That does not mean they cannot, they simply do not. That might be a demand issue more than a supply issue.

Perhaps seven percent of those homes simply do not wish to buy internet access, or about 3850 households. That implies 51,150 households that either cannot currently buy internet access; have access but not at 25 Mbps or choose to use mobile access instead.

Mobile-only households might be 15 percent to 20 percent of all homes. Use the lower figure. At 15 percent, that implies 8250 households prefer to use mobile access in place of fixed access. So the potential pool of customers for the $30 subsidies might be 42,900.

It is not clear that all those households would qualify for, or use, the $30 subsidies, though. Nor is it clear that the new subsidy actually increases adoption very much.

There are other assistance programs already in place. For example,98,000 households might qualify for the $30 subsidy as recipients of support from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Medicaid recipients also are eligible. So are students receiving Pell grants.

But most internet service providers already were providing low-cost internet access for low-income customers,supplying 25 Mbps access at prices between $5 and $15 a month.

The point is that low-cost 25 Mbps access already has been available to households at prices between $5 and $15 a month from all the major suppliers. It is not clear how many low-income households that want internet access were not already buying.

source: High Speed Internet.com

The point is that the $30 subsidies are more likely to shift demand from some service plans to others than to cause non-subscribers to become subscribers, since the subsidies can be used to defray consumption of any tier of service.

In that sense, allocating half the estimated $300 million to service subsidies might have relatively slight impact. The bigger problem might be lack of any service, and inability to buy any grade of service faster than 25 Mbps.

So there is likely a public policy argument for spending most of the broadband funds on infrastructure improvements, rather than additional service subsidies.