Many telcos--or those who advise and sell to them--say telcos need to become techcos. So what does that mean?

At least as outlined by Mark Newman, Technotree chief analyst and Dean Ramsay, principal analyst, there are two key implications: a culture shift and a business model.

The former is more subjective: telco organizations need to operate “digitally.” The latter is harder: can telcos really change their business models; the ways they earn revenue; their customers and value propositions?

source: TM Forum

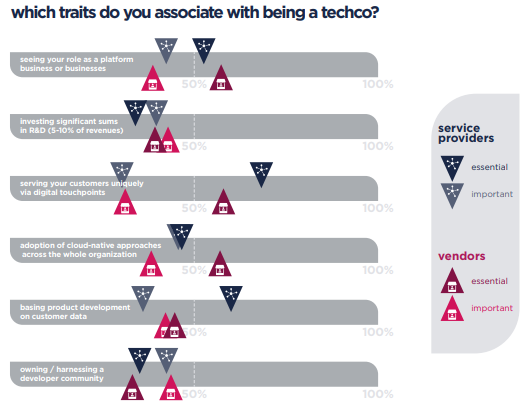

It might be easier to describe the desired cultural or technology changes, even without a change in business model. Digital touchpoints; higher research and development spending; use of native cloud computing; a developer mindset and data-driven product development.

Most of us might agree that doing such things is good, but does not necessarily mean telcos become something else.

The key to possible business model changes comes specifically with the notion that telcos can become “platforms.” And even that overused term is subject to huge differences of meaning. Some use the classic “computing” definition that a platform is “hardware or software that other software can run on.”

Think “operating system” or even containers, program application interfaces, languages or X as a service as examples. In that sense, telcos might hope to become “techcos” by advancing their capabilities as application enablers.

There is a tougher definition, though. A platform business model essentially involves becoming an exchange or marketplace, more than remaining a direct supplier of some essential input in the value chain. It is, in short, to function as a matchmaker. That is a different business model entirely.

For most of history, most businesses have used a pipe model, creating and then selling products to buyers.

The platform facilitates selling and buying. A pipe business focuses more on efficiency in its value chain, where a platform focuses more on orchestrating interactions between members.

The platform allows participants in the exchange to find each other.

Platforms are built on resource orchestration; pipes are built on resource control. Value quite often comes from the contributions made by community members rather than ownership or control of scarce inputs vertically integrated by a supplier.

In other words, using a “computer function” definition of “platform” implies one set of changes; using the “business model” definition is something else entirely.

The point is that as useful as the phrase “we are not a telco; we are a techco” might be, it is marketing jargon. “Being digital” or “moving fast” or “being cloud native” or “boosting research and development” arguably are cultural changes many businesses can benefit from.

It is not so clear that such changes (equivalent perhaps to the change from analog to digital) necessarily change a business model, though they might often improve the existing model.

As helpful as it should be to adapt to native cloud, developer-friendly applications and networks, use data effectively or boost research or development, none of those attributes or activities necessarily changes the business model.

If “becoming a techco” means lower operating costs; lower capital investment; faster product development or happier customers, that is a good thing, to be sure. Such changes can help ensure that a business or industry is sustainable.

The change to “techco” does not necessarily boost the equity valuation of a “telco,” however. To accomplish that, a “telco” would have to structurally boost its revenue growth rates to gain a higher valuation; become a supplier of products with a higher price-to-earnings profile, higher profit margins or business moats.

What would be more relevant, then, is the ability of the “change from telco to techco” to serve new types of customers; create new and different revenue models; develop higher-value roles and products or add new roles “telcos” can perform in the value chain or ecosystem.

That is the profound meaning some of us would say “techco” represents, if it can be achieved. To what extent can “telcos” earn lots of money--perhaps most of their money--from acting as a marketplace, rather than as creators and sellers of products built around connectivity?

To be sure, if “becoming a techco” has other intermediate value, such as boosting revenues and profits while reducing costs and speeding new product creation, the process would still have value.

It would perhaps be the business model equivalent of the transition from analog to digital processes overall. That is important, but does not transform a telco into something else, which is what all the verbiage about “techco” implies.

It is too early to assess whether “techco” is simply a change in marketing hype or something more profound.