Digital infrastructure investing, like alternative asset investing generally, now has moved to embrace core plus concepts. The nomenclature comes from the traditional real estate investment concepts used by buyers of alternative assets.

Some might say “core” assets are akin to Class A office buildings, which are the most prestigious in a city. Class B buildings might be those which offer fewer prestige value than class A, and might be located outside a downtown core area. Class C buildings will tend to be aimed at more industrial or service oriented businesses and smaller businesses.

source: Bullpen

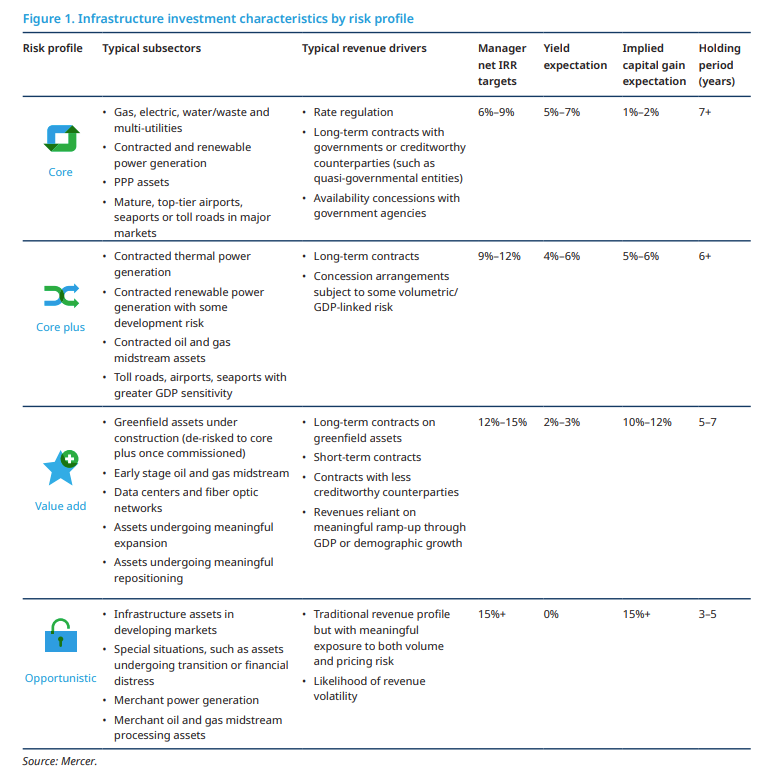

It might be more accurate to characterize the different classes of assets by risk and return profiles, as there is less the notion of “prestige” as in office space, and more the fact that digital infra is a newer class of alternative or real estate assets, albeit with generally higher exposure to economic cycles and less business moat protection.

As the range of infrastructure assets has grown, some now see more gradations of risk, adding “supercore” as a category of regulated assets, to distinguish between other assets that are not formally rate or price regulated.

By definition, digital infra assets would not be considered supercore, as data center, cell tower, fiber network and other “telecom” network assets are unregulated in terms of pricing and do not offer guaranteed rates of return.

In a private equity or other institutional investment context, “core” infrastructure has meant gas or electricity utilities that have business moats, offer predictive cash flow and are relatively resistant to economic fluctuations. These businesses also tend to be rate regulated, with low capital appreciation, longer asset holding cycles and lower yield.

That profile fits requirements of large pension funds and other institutional investors including sovereign wealth funds, for example.

“Core plus” adds new classes of assets such as airports, seaports, roads that have more exposure to economic cycles but higher capital gain potential, balanced by potentially less predictable cash flow.

Data centers, specialized fiber networks, edge computing facilities, fiber-to-home networks, towers and hosting facilities are considered “value add” assets. Capital gain potential is higher, assets holding periods might be shorter and yield is expected to be lower.

“Opportunistic” assets might be digital infra in developing markets or distressed assets.

source: Mercer

Yet others will use a related taxonomy using “super core” (core); core (what others might call core plus) and core plus (what others might call value add).

As always, people will disagree about the boundaries between asset classes or the placement of specific assets within a class. Some argue that “core” infrastructure includes assets which are primarily income-producing. That view groups toll roads, bridges and hospitals in the same grouping with gas and electrical utilities.

Also, some now view “core infrastructure” as including mobile towers, cloud storage and data centers. In that typology, some would say core plus/value add is a different category.

The classification scheme matters to the extent that it guides investment thinking about what is core and what is “core plus'' or “value add.”

The obvious areas of disagreement are that some assets viewed as “core plus” by some will be considered “core” by others. In a digital infra context, that means deciding whether data centers, tower networks and fiber access networks are “core” or “core plus.”

The same definitional issue is whether those sorts of assets are “core plus” or “value add.” Perhaps nobody is going to confuse those categories with “opportunistic” investments which involve some level of asset distress or uncertainty.

Digital infra, as viewed by many, has become an “essential” sort of infrastructure akin to roads, airports, seaports, electricity and natural gas supply. If so, then cell towers, fiber networks and data centers are “core” assets. So “core plus” and “value add” are the adjacencies to be explored, aside from the occasional “opportunistic” play.

As a practical matter, digital infra investors tend to view those assets as core. Historically, infrastructure investors have looked for investments that:

are real, capex-intensive assets

are essential services

offer steady and stable returns

Are economic cycle protected

provide cash yields

have barriers to entry

are typically within energy, telecom or transport.

Most observers would likely agree that “core plus” means any additional new asset classes or assets with less utility-like characteristics. That might mean assets with shorter-term contracts, no rate regulation and some exposure to economic cycles, though generally regarded as “essential” facilities and functions.

With the emergence of “supercore” asset baskets that consist exclusively of assets with regulated pricing, it seems logical to include data centers, tower networks, edge computing facilities or fiber networks as “core.”