Structural separation of retail opeations from network ownership was a bigger idea several decades ago than at present, even if a handful of markets have moved that way in a formal sense in Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

The key idea is to create an independent network faciltiies supplier and allow all retail service providers to use that one platform.

Whether mandated by regulators or as a business choice, wholesale access remains contentious in both fixed and mobile segments of the business. Over the decades, one has heard much criticism of the “I build it, you get to use it” argument from facilities providers selling wholesale capacity and services to retail competitors.

Such complaints happen in a variety of settings, including mobile and fixed network wholesale; whether featuring mandated pricing set by regulators or market mechanisms; and by business strategy and market share (attacking or smaller facilities-based suppliers often see greater advantages than dominant providers).

It remains unclear how attitudes of underlying carriers could change in the future, if greater functional separation of mobile or fixed assets were to occur, especially if it is not mandated by government authorities.

In other words, if the ownership of access or core network facilities continues to evolve, with greater ownership by private equity, institutional investors and other “patient” investors, how much could attitudes shift?

If “core” network assets are only partially owned or even divested by dominant retail suppliers, do attitudes also shift? If core infrastructure no longer is considered strategic by dominant suppliers--as unlikely as that might seem--do most, if not all retail service providers wind up having similar attitudes about the value of wholesale access and their business models?

As an example, what if BT Openreach is fully separated from BT? How does BT’s valuation of core network assets (access, especially) evolve? Does BT not acquire the same positon as any existing wholesale customer of Openreach?

Beyond that, what emerges as the core competency of a dominant retailer once ownership of the scarce access facilities is no longer an issue? The perhaps obvious answers are market share itself, installed name, brand name awareness and value, influence on the regulatory process, other complementary assets and so forth.

Right now, the mobile virtual network operator business model provides some baselines.

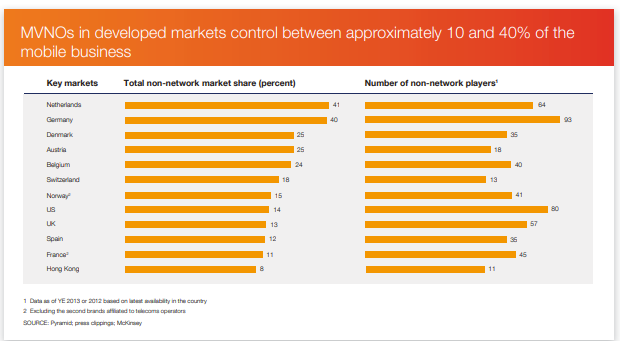

MVNOs are not legal in every market, but in some markets represent significant portions of the installed base and market share. That is especially true in Europe.

source: McKinsey

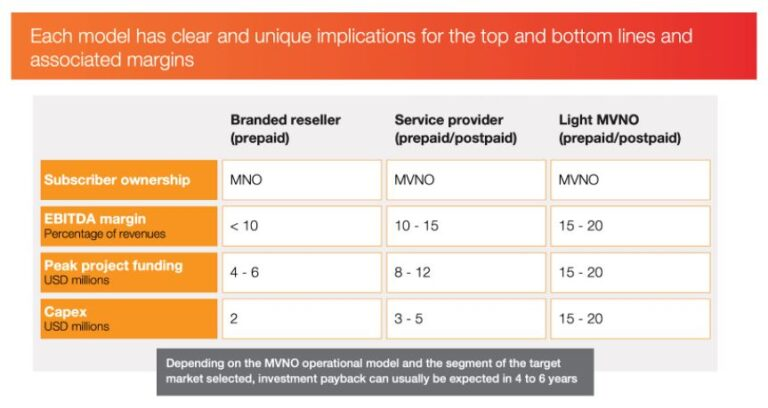

Margin potential varies. Simple branded “resellers” who add little additional value also face the least risk, at the cost of expected profit margins. Basically, this business model relies on sales and marketing skill, as the basic “product” is sourced completely from a facilities-based service provider, with no fundamental differentiation. The reseller is not able to set its own retail prices.

An MVNO operating as a “service provider” assumes more risk, for more potential reward. A service provider operates its own direct billing and customer care operations and can set its own prices. Revenue is typically earned on outbound traffic.

The “asset light” MVNO earns revenue on both outbound and inbound traffic, and is obliged to pay the underlying carrier on a pattern similar to the “service provider” MVNO. The main advantage is that this type of MVNO is free to add any sort of additional value and differentiation.

A “full MVNO” itself supplies all of the infrastructure except the radio access network, which is leased from a facilities-based mobile operator. This model offers perhaps the highest ability to differentiate the user experience, with the highest amount of risk, however.

As a rule, an MVNO has to have operating costs 30 percent or more lower than the host provider’s cost structure. Perhaps for that reason, the full MVNO model is rarely chosen. The center of gravity is arguably either the service provider or asset light approach.

Much can hinge on the anticipated gross revenue and profit margins to the wholesale services supplier. Bulk accounts have their attractions. If some customers want to defect to a lower-cost mobile virtual network operator--and that is the primary attraction for nearly all MVNOs--then supplying access to a retail competitor still makes business sense.

The underlying carrier makes revenue off a “lost” customer account. Some argue that asset-light MVNOs can earn higher profit margins than facilities-based retailers.

source: Oxio

If a dominant mobile service provider could achieve margins between 15 percent and 20 percent as do other light MVNOs, but avoid capex and opex, further boosting margins, would that not be a reasonable choice?

And if so, the historic value of owning scarce access assets decreases substantially, perhaps nearly entirely. So the business model becomes more disaggregated.

Structural separation, in past decades mostly viewed as a regulatory solution, might eventually become a preferred marketplace solution.