Today, the average user carries three mobile devices, and by 2016, they will carry closer to seven, according to ZK Research. Wi-Fi networks will have to get faster, it is reasonable to assume. And most studies show a clear preference by users for Wi-Fi access when using their e-readers, notebook PCs, tablets and smart phones.

Monday, December 3, 2012

Wi-Fi Will Have to Get Faster

Today, the average user carries three mobile devices, and by 2016, they will carry closer to seven, according to ZK Research. Wi-Fi networks will have to get faster, it is reasonable to assume. And most studies show a clear preference by users for Wi-Fi access when using their e-readers, notebook PCs, tablets and smart phones.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

What Will Apple Do "After" iPhone?

Gene Munster of Piper Jaffray says Apple's history of cannibalizing its own businesses will lead Apple even to cannibalize the iPhone and iPad, its current and apparently next big revenue drivers.

Munster predicts consumer robotics, wearable computers, 3D printing, consumable computers, and automated technology might someday be the products Apple is known for creating.

Munster predicts consumer robotics, wearable computers, 3D printing, consumable computers, and automated technology might someday be the products Apple is known for creating.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Text messaging turns 20

The first SMS was sent as a Christmas greeting in December 1992, the Guardian notes. Adoption took a while, and was not terribly widely used in all markets. In fact, text messaging began to get serous traction around the year 2000. So it was eight years before lots of people started to use the new too..

That's worth keeping in mind: even the most-useful consumer innovations can take some time to become widespread.

As a rule of thumb, an innovation that becomes widely used starts to grow much faster once it reaches about 10 percent penetration. But how long it takes to reach 10 percent can vary widely.

Looking only at AT&T, you can see that text messaging volumes did not actually begin to build until after 2007, for example, despite having been available for more than a decade prior.

And even in the United Kingdom, where consumers adopted the text messaging habit earlier, you can see that dramatic growth happened sometime around 2000.

Roughly the same trend can be noted for global usage. Growth accelerated only around 2000.

That's worth keeping in mind: even the most-useful consumer innovations can take some time to become widespread.

As a rule of thumb, an innovation that becomes widely used starts to grow much faster once it reaches about 10 percent penetration. But how long it takes to reach 10 percent can vary widely.

Looking only at AT&T, you can see that text messaging volumes did not actually begin to build until after 2007, for example, despite having been available for more than a decade prior.

And even in the United Kingdom, where consumers adopted the text messaging habit earlier, you can see that dramatic growth happened sometime around 2000.

Roughly the same trend can be noted for global usage. Growth accelerated only around 2000.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Will Service Providers Integrate Public Hotspot Access in a More Active Way?

Up to this point, Wi-Fi has been important for high-speed access providers mostly in an indirect way. Generally speaking, public hotspots have been an amenity offered to paying customers (either fixed or mobile broadband). The business value then is “stickiness,” as the perceived value of a particular offer is higher.

But that might change, with public Wi-Fi possibly becoming a “for fee” service, according to Monica Paolini, owner of Senza Fili Consulting. The extent of end user demand for such changes is unclear. Much would depend on new additional value.

But a number of developments might propel the change. Increased use of VoIP applications over Wi-Fi means low latency and jitter performance is more important, and “best effort” public hotspots might not work well enough to suit all users. A quality-assured approach would help. That might create a new level of value that service providers might be able to charge for.

Business customers might be logical customers, as has generally been the case for other third-party public Wi-Fi networks. Among other advantages, shifting traffic to Wi-Fi hotspots would help enterprise information technology managers avoid expensive data overage charges.

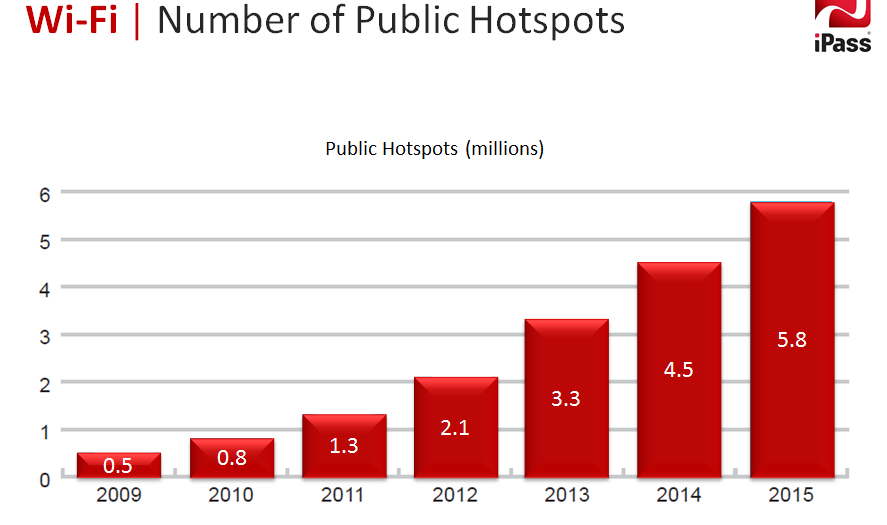

Business Wi-Fi provider iPass, for example, projects it will offer a vastly-bigger network by 2015.

The advent of fourth generation Long Term Evolution networks might have other unintended consequences. Up to this point, people generally have understood that a public hotspot will offer access speeds greater than 3G.

That might not generally be true for 4G networks. That might limit the amount of traffic offloading, which, in turn, might increase congestion on the LTE networks.

Also, some lighter users, and that is likely a clear majority of smart phone users, don’t necessarily have any incentives to switch to Wi-Fi hotspot access.

Heavier users will have incentives, as use of Wi-Fi preserves data allowances. So some think a quality-assured access, even for a fee, might be feasible and perhaps necessary. By 2015, Cisco projects that as much as 46 percent of all Internet traffic will use a Wi-Fi connection.

The value could be that the service provider mixes and matches acces to provide the best performance. Part of the value might also include applying such mechanisms only when the subscriber is not in danger of exceeding a mobile data allowance. Alternately, such access decisions could be set by the consumer to apply only when the user is on a business trip or requires absolute best performance.

Users might also see value if they are allowed to apply their own policies, such as watching video only on Wi-Fi, but IP voice always over the best available connection.

Price-sensitive subscribers might also want an automatic switch to Wi-Fi access at all times.

The point is that there are growing reasons to integrate and manage public Wi-Fi, private Wi-Fi and mobile network access in a more deliberate way.

But that might change, with public Wi-Fi possibly becoming a “for fee” service, according to Monica Paolini, owner of Senza Fili Consulting. The extent of end user demand for such changes is unclear. Much would depend on new additional value.

But a number of developments might propel the change. Increased use of VoIP applications over Wi-Fi means low latency and jitter performance is more important, and “best effort” public hotspots might not work well enough to suit all users. A quality-assured approach would help. That might create a new level of value that service providers might be able to charge for.

Business customers might be logical customers, as has generally been the case for other third-party public Wi-Fi networks. Among other advantages, shifting traffic to Wi-Fi hotspots would help enterprise information technology managers avoid expensive data overage charges.

Business Wi-Fi provider iPass, for example, projects it will offer a vastly-bigger network by 2015.

The advent of fourth generation Long Term Evolution networks might have other unintended consequences. Up to this point, people generally have understood that a public hotspot will offer access speeds greater than 3G.

That might not generally be true for 4G networks. That might limit the amount of traffic offloading, which, in turn, might increase congestion on the LTE networks.

Also, some lighter users, and that is likely a clear majority of smart phone users, don’t necessarily have any incentives to switch to Wi-Fi hotspot access.

Heavier users will have incentives, as use of Wi-Fi preserves data allowances. So some think a quality-assured access, even for a fee, might be feasible and perhaps necessary. By 2015, Cisco projects that as much as 46 percent of all Internet traffic will use a Wi-Fi connection.

The value could be that the service provider mixes and matches acces to provide the best performance. Part of the value might also include applying such mechanisms only when the subscriber is not in danger of exceeding a mobile data allowance. Alternately, such access decisions could be set by the consumer to apply only when the user is on a business trip or requires absolute best performance.

Users might also see value if they are allowed to apply their own policies, such as watching video only on Wi-Fi, but IP voice always over the best available connection.

Price-sensitive subscribers might also want an automatic switch to Wi-Fi access at all times.

The point is that there are growing reasons to integrate and manage public Wi-Fi, private Wi-Fi and mobile network access in a more deliberate way.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

EC Proposes Higher Wholesale Access Prices

European Commission telecom regulators apparently are circulating a draft proposal creating a new regulatory framework intended to spur faster investment in next generation fiber to the home networks. The general outlines appear consistent with approaches taken earlier by U.S. regulators that had to balance “investment” and “competition” incentives to encourage more investment in fiber to home facilities.

Among the key proposed changes is an increase in prices network owners can charge competitors who lease access circuits, network elements and infrastructure, as well as a suspension of mandatory wholesale price rules for the new fiber to home networks.

The rules would first raise revenue for the incumbents leasing capacity to rivals, and then allow setting of commercial rates for future access to the fiber to home facilities. Both moves would aim to bolster incumbent finances while creating clearer incentives for investing in fiber to home networks.

The plan illustrates once again how telecom regulators can directly affect competitor revenue and cost assumptions and business plans.

Under the new plan,, monthly rental access prices per customer would range between eight and 10 euros by the end of 2016. That would mean higher charges paid by competitive carriers in 10 EU countries including the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Hungary and Estonia, which currently offer rates below eight euros.

On the other hand, Ireland, which currently has the highest monthly cost at 12.41 euros, Finland, Britain and Luxembourg would have to bring their prices down.

The EC has been looking at wholesale rates as part of a wider effort to create incentives for investment in faster fiber to home networks. The investment problem, up to this point, has been that incumbent carriers have seen little reason to invest heavily under circumstances where the fiber network rates are highly regulated.

Of particular concern are rules that set wholesale access rates too low, thereby reducing the revenue earned from selling competitors wholesale access to those new networks.

The very same argument occurred in the U.S.market, for precisely the same reasons, with essentially the same format adopted.

In the U.S. market, after a period of mandatory and significant wholesale discounts, wholesale access to copper and all fiber facilities was deregulated, allowing market rates to be set by contracts, rather than relying on mandatory price rules.

The issue in the U.S. market, as in the EC, was that incumbent carriers argued they could not upgrade to fiber facilities because the steep discounts did not allow them to earn a reasonable return on invested capital.

In North America and Europe, it increasingly seems as though regulators can have “more competition” or they can have “ more investment,” but not both, in the fixed network realm.

In order to reach the European Community’’s “Digital Agenda” goal of at least half of EC residents able to access broadband at 100Mbps or more by 2020, the EC has been looking at how the regulatory environment can support and stimulate investment in next-generation networks. The draft proposal is the result of that investigation.

Essentially, regulators have two fundamental choices: mandate aggressive wholesale rules to spur competition, or allow service providers to “keep” the potential revenue from investment in new facilities by relaxing wholesale obligations.

In the U.S. market, after an extensive experiment with mandatory wholesale access with hefty discounts, triggered by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, regulators had to make a choice.

The major facilities-based access providers essentially signaled that they were not going to make major investments in new optical infrastructure so long as mandatory access with hefty discounts remained policy, especially when a rival broadband network, already operated by a local cable operator, already was in business, without any mandatory access obligations at all.

Eventually, to the chagrin of competitors, the Federal Communications Commission reversed course, allowing incumbents to charge market-based rates, in return for heavier investment in new optical access.

Historically, European regulators, operating in markets where there had not been robust deployment of cable broadband, favored heavy use of wholesale access.

But in a significant “u turn,” European Community telecom commissioner Neelie Kroes backed off a plan to increase the discounts offered to third parties who buy wholesale access from incumbent European Union service providers.

Clearly, such a plan would have further reduced carrier incentives to invest in new fiber plant. For competitors, the new rules also would raise operating costs, making it harder to compete.

But that's the dilemma regulators face: encouraging competition by mandating lower wholesale rates also decreases incentives for facilities owners to invest in new optical plant.

Among the key proposed changes is an increase in prices network owners can charge competitors who lease access circuits, network elements and infrastructure, as well as a suspension of mandatory wholesale price rules for the new fiber to home networks.

The rules would first raise revenue for the incumbents leasing capacity to rivals, and then allow setting of commercial rates for future access to the fiber to home facilities. Both moves would aim to bolster incumbent finances while creating clearer incentives for investing in fiber to home networks.

The plan illustrates once again how telecom regulators can directly affect competitor revenue and cost assumptions and business plans.

Under the new plan,, monthly rental access prices per customer would range between eight and 10 euros by the end of 2016. That would mean higher charges paid by competitive carriers in 10 EU countries including the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Hungary and Estonia, which currently offer rates below eight euros.

On the other hand, Ireland, which currently has the highest monthly cost at 12.41 euros, Finland, Britain and Luxembourg would have to bring their prices down.

The EC has been looking at wholesale rates as part of a wider effort to create incentives for investment in faster fiber to home networks. The investment problem, up to this point, has been that incumbent carriers have seen little reason to invest heavily under circumstances where the fiber network rates are highly regulated.

Of particular concern are rules that set wholesale access rates too low, thereby reducing the revenue earned from selling competitors wholesale access to those new networks.

The very same argument occurred in the U.S.market, for precisely the same reasons, with essentially the same format adopted.

In the U.S. market, after a period of mandatory and significant wholesale discounts, wholesale access to copper and all fiber facilities was deregulated, allowing market rates to be set by contracts, rather than relying on mandatory price rules.

The issue in the U.S. market, as in the EC, was that incumbent carriers argued they could not upgrade to fiber facilities because the steep discounts did not allow them to earn a reasonable return on invested capital.

In North America and Europe, it increasingly seems as though regulators can have “more competition” or they can have “ more investment,” but not both, in the fixed network realm.

In order to reach the European Community’’s “Digital Agenda” goal of at least half of EC residents able to access broadband at 100Mbps or more by 2020, the EC has been looking at how the regulatory environment can support and stimulate investment in next-generation networks. The draft proposal is the result of that investigation.

Essentially, regulators have two fundamental choices: mandate aggressive wholesale rules to spur competition, or allow service providers to “keep” the potential revenue from investment in new facilities by relaxing wholesale obligations.

In the U.S. market, after an extensive experiment with mandatory wholesale access with hefty discounts, triggered by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, regulators had to make a choice.

The major facilities-based access providers essentially signaled that they were not going to make major investments in new optical infrastructure so long as mandatory access with hefty discounts remained policy, especially when a rival broadband network, already operated by a local cable operator, already was in business, without any mandatory access obligations at all.

Eventually, to the chagrin of competitors, the Federal Communications Commission reversed course, allowing incumbents to charge market-based rates, in return for heavier investment in new optical access.

Historically, European regulators, operating in markets where there had not been robust deployment of cable broadband, favored heavy use of wholesale access.

But in a significant “u turn,” European Community telecom commissioner Neelie Kroes backed off a plan to increase the discounts offered to third parties who buy wholesale access from incumbent European Union service providers.

Clearly, such a plan would have further reduced carrier incentives to invest in new fiber plant. For competitors, the new rules also would raise operating costs, making it harder to compete.

But that's the dilemma regulators face: encouraging competition by mandating lower wholesale rates also decreases incentives for facilities owners to invest in new optical plant.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Still Time to "Harvest" Video Revenues

The number of U.S. telco video subscribers will rise from 8.8 million in 2011 to 18.6 million in 2017, according to Parks Associates now forecasts. That gain by telcos will come from share presently held by cable TV customers and satellite providers.

Satellite's share of the subscription video market will drop to 30 percent by 2017, while cable's share will fall to 52 percent, while telco IPTV share will rise to 18 percent.

Cable video subscribers will decline from 60.7 million in 2011 to 56.1 million in 2017.

Those figures show the difference between incumbent and attacking providers in a mature market. Under those conditions, “harvesting” is a typical business strategy for leading contestants in declining markets.

When executives believer there is no real opportunity to reverse a product slide into the declining side of its product life cycle, it makes sense to harvest cash, but not to invest too much to “save” the business, or turn it around, as the judgment simply is that the business is mature and inevitably will decline.

It does make sense to invest only enough to slow the rate of decline, of course. Attackers, on the other hand, can do nicely for a while simply by taking market share.

Video is largely becoming a harvesting exercise for cable operators, just as long distance calling and legacy voice are examples of “harvesting” by telcos.

As the attacker in voice and business services, cable operators still can grow revenue in the near term, as telcos can grow revenue in video. Over the longer term, though, even attackers can only achieve so much, in a maturing market.

For cable, consumer voice revenues have ceased to be much of a growth business, which explains the shift to business customers. Telcos and satellite video providers still have room to continue taking video share, though. Sooner or later, that might run into resistance, especially if over the top video, featuring the same content now part of video subscriptions, takes off.

A new ABI Research study suggests that nearly 20 percent of online video consumers consider online video as a replacement for entertainment video subscriptions. That obviously represents “significant risk” to the traditional video entertainment business.

ABI Research suggests the magnitude of potential revenue loss could range as high as $16.8 billion in the U.S. market, for example. Telcos won’t face those issues, as they are predicted by virtually every study to continue taking market share, as cable TV operators and satellite providers continue to lose market share over time.

But at least one analysis has satellite providers overtaking cable TV providers in revenue in 2017.

So the near term trends might not be “linear,” as some forecasters still project cable TV operator and satellite provider video revenues growing for a period, Digital TV Research forecasts.

But a change that shaves as much as $17 billion from U.S. providers would seem to be a longer-term danger, as ABI Research also suggests U.S. video entertainment penetration is dropping at a rate of about 0.5 percent per year through 2017.

That arguably is an optimistic scenario for cable TV providers. Ignoring changes of market share between the contestants, a loss of perhaps half a percent a year of subscribers won’t make a large dent in a revenue stream that collectively represents more than $90 billion in annual revenue.

If the number of subscribers were directly related to the amount of revenue, then a half percent a year decline would represent perhaps $450 million in lost revenue each year. At such rates, it would take decades before service providers lost $17 billion.

Whatever share shift one expects, the game now for video service providers is to “take or protect” market share.

North America pay TV revenues ($ mil.)

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Why Google, Facebook, Apple "Mobile Service Provider" Rumors Never Cease

From time to time there are new rumors that Facebook, Apple or Google "might" become mobile service providers, using a mobile virtual network operator model. Some think it doesn't make sense.

But the rationale for being a mobile service provider is a bit more complicated than it used to be. For starters, "voice" revenue is not the only reason for doing so. These days, Internet access makes almost as much sense.

Also, for application providers with other revenue models, becoming a service provider would allow creation of packages and plans that cold be much more differentiated than currently are available from the leading mobile service providers.

But the lure of revenue might still be important. In the global telecom business, there have been complaints for years from telecom executives that third party app providers build businesses on the back of telco-provided access services, but that the access providers do not share in the revenue created.

In a potentially new development, some application providers might be taking a similar view, sensing that they create huge value for telcos, but do not participate in the access revenue stream, for example.

Strand Consult now speculates on whether Facebook, for example, is willing to look beyond advertising as a source of revenue, and whether Facebook would become a mobile virtual network operator, as a way to create a new revenue stream, as well as recapture some of the value it believes it is creating in the ecosystem.

As some have speculated about the value of Facebook creating its own branded smart phone, Strand Consult now speculates about the value of Facebook becoming a service provider.

Becoming an “MVNO is a logical step for Facebook the world’s largest communication platform,” Strand Consult analysts argue.

One billion users already consider Facebook as their de facto telephone book for friends and family and use the platform for communicating by SMS, text, image and video, the firm argues.

Aside from its huge user base, Facebook has credit card credentials on file already for millions of its users, many of whom purchase premium games, driving one sixth of Facebook’s revenue.

How much could Facebook earn as an MVNO? Facebook currently earns annual revenue per user of $4. An MNVO can earn between $10 a month and $50 a month per customer with an operating margin between 20 percent and 25 percent.

Facebook arguably is in no mood to consider such diversions. But Google or Apple, both with key application and gadget businesses, might have more motivation to do so.

But the rationale for being a mobile service provider is a bit more complicated than it used to be. For starters, "voice" revenue is not the only reason for doing so. These days, Internet access makes almost as much sense.

Also, for application providers with other revenue models, becoming a service provider would allow creation of packages and plans that cold be much more differentiated than currently are available from the leading mobile service providers.

But the lure of revenue might still be important. In the global telecom business, there have been complaints for years from telecom executives that third party app providers build businesses on the back of telco-provided access services, but that the access providers do not share in the revenue created.

In a potentially new development, some application providers might be taking a similar view, sensing that they create huge value for telcos, but do not participate in the access revenue stream, for example.

Strand Consult now speculates on whether Facebook, for example, is willing to look beyond advertising as a source of revenue, and whether Facebook would become a mobile virtual network operator, as a way to create a new revenue stream, as well as recapture some of the value it believes it is creating in the ecosystem.

As some have speculated about the value of Facebook creating its own branded smart phone, Strand Consult now speculates about the value of Facebook becoming a service provider.

Becoming an “MVNO is a logical step for Facebook the world’s largest communication platform,” Strand Consult analysts argue.

One billion users already consider Facebook as their de facto telephone book for friends and family and use the platform for communicating by SMS, text, image and video, the firm argues.

Aside from its huge user base, Facebook has credit card credentials on file already for millions of its users, many of whom purchase premium games, driving one sixth of Facebook’s revenue.

How much could Facebook earn as an MVNO? Facebook currently earns annual revenue per user of $4. An MNVO can earn between $10 a month and $50 a month per customer with an operating margin between 20 percent and 25 percent.

Facebook arguably is in no mood to consider such diversions. But Google or Apple, both with key application and gadget businesses, might have more motivation to do so.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Will AI Disrupt Non-Tangible Products and Industries as Much as the Internet Did?

Most digital and non-tangible product markets were disrupted by the internet, and might be further disrupted by artificial intelligence as w...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

Who gets to use spectrum, and concerns about interference from other users, now appears to be an issue for Google’s Project Loon in India. ...