While the decline of voice and text messaging prices is not welcome in the mobile business, and though the pace of decline matters greatly, not every executive, at least in public, is excessively worried about the maturation of traditional products.

The acquisition of WhatsApp by Facebook, for example, does not worry Olaf Swantee, EE CEO. That public calm is possible because EE does not rely on text messaging revenues to drive its growth, Swantee insists.

That is an optimistic prediction, when text messaging still drives about a third of revenue growth for a mobile service provider, and represents scores of billions of revenue.

“It is not something we need to compete with,” said Swantee about over the top messaging, pointing out that EE revenue growth is driven principally by the acquisition of additional postpaid mobile service contracts and mobile data plans.

“SMS revenues and usage will come down over time,” Swantee said.

WhatsApp recorded an all-time high of 10 billion outgoing messages in a single day in June 2013, which equated to an average of more than 30 messages per user per day, according to Stephen Sale, Analysys Mason principal analyst.

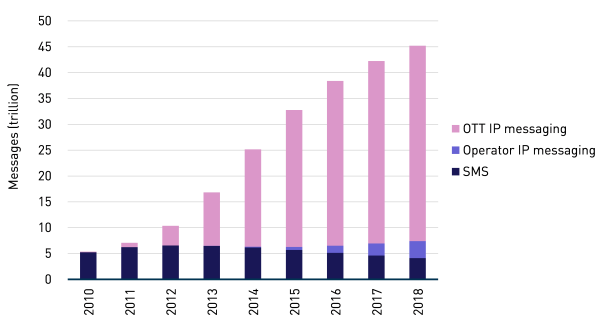

“We estimate that the total volume of messages sent from mobile devices via IP services exceeded the volume of SMS messages for the first time in 2013, at more than 10.3 trillion compared with 6.5 trillion worldwide,” said Sale. “Messaging volumes associated with OTT services are expected to almost double in 2014 and will reach 37.8 trillion messages sent in 2018.”

“It is only a matter of time before SMS services are dislodged from their current default position on smartphones,” said Sale.

Mobile Messaging Forecast

On the other hand, EE revenue growth clearly is weighted towards account gains and mobile broadband. Data and messaging revenues reached 56 percent of total EE average revenue per user in the fourth quarter of 2013, compared to 50 percent of total revenue in the fourth quarter of 2012, with data (non-text) revenue up to 44 percent of ARPU compared to 34 percent in the fourth quarter of 2012, EE says.

EE also says its 4G customer base grew 68 percent from the third quarter of 2013 to the fourth quarter of 2013.

After adding 194,000 postpaid net adds in the fourth quarter of 2013, 58 percent of the EE customer base now is postpaid, excluding machine-to-machine (M2M), delivering six times more ARPU than prepaid.

The prepaid base meanwhile dipped 543,000, EE says.