It is not yet clear whether video entertainment facing internet disruption will follow the path of the music and print media industries, or somehow can evolve in a way similar to retailing. In other words, will the future video entertainment business be bigger or smaller than the linear business it displaces?

It is conventional wisdom these days that video streaming has failed to replace losses from linear TV subscription declines. In some ways, the comparison is a bit unfair. Streaming is a new business, which means development costs and investments are high, compared to customers and revenue, as generally is true for most new lines of business being created for the first time.

Linear video subscriptions are a declining line of business, but can be harvested for revenue without undue investments. So we are comparing a declining business with a growing and new line of business. One can harvest revenues from a legacy business. One has to invest to grow a new one.

Also, in a linear video model, content providers can spend less on delivery infrastructure, as the distributor takes care of that. In a streaming model, the delivery infrastructure has to be built.

In the linear model, content provider marketing costs are lower, as the distributor takes primary charge of that function and absorbs the cost. In a direct-to-customer streaming model, the content provider has to spend more on marketing and sales.

There are other differences as well. Customer churn--which increases operating costs--for streaming services is higher than for linear TV services. One big reason is that customers can binge watch a hot new series and then churn off once they are finished.

Also, a linear video package is itself a bundle, with economy of scope advantages. Most buyers are aware that buying in bulk correlates with lower cost per unit. Unbundling content eliminates much of that advantage. To be sure, any single streaming service remains a bundle of content.

If you think about one of the main complaints about linear TV, which is that customers pay for products they do not use, you get the idea. The linear bundle increases profits for the whole ecosystem because customers are forced to buy products they do not want, do not use, do not value.

The economic argument is quite similar to that the industry debated a couple of decades ago: whether unbundled, a la carte network access would at least be revenue neutral compared to the existing cable TV bundle. A la carte sales models imply lower ad revenues, lower subscriber counts and therefore lower subscription revenues.

In principle, ability to buy content “by the piece or by the episode” allows customers to buy only what they want. And consumers resonate with that idea. The issue is whether content suppliers can afford to grant access at sustainable prices. Consumers almost always value a bit of content less highly than the content owners selling it.

Most consumers already have discovered they need more than one streaming service to satisfy their needs. Ironically, that defeats the purported value of “lower prices” for any single streaming service.

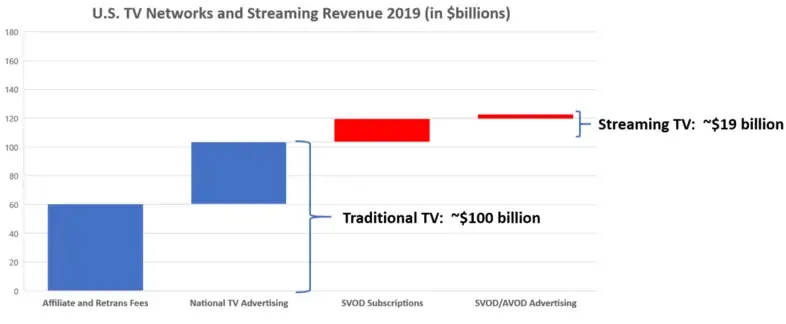

But content scope never is as great as with a linear package, which delivers many networks. Each streaming service is, in essence, a single network. Today, most content providers make most of their money selling content rights to cable TV providers. As that revenue stream shrinks, it is poised to shrink faster than streaming revenues can replace the losses.

source: MoffettNathanson

Of course, the linear video model has gotten more precarious for lots of reasons beyond the existence of video streaming alternatives. As content prices have kept climbing, it was inevitable that the cable TV bundle would reach a level where the value-cost relationship would be seen as unfavorable by a growing number of consumers.

Unbundling video content access almost inevitably leads to higher costs per unit, for suppliers and consumers. It is possible a smaller industry therefore results, as less-popular networks get squeezed out.

Of course, under some circumstances, unbundling also might allow some niche content to thrive. As has become the case in the music industry, where consumers now buy “songs” a la carte rather than “albums” (a bundle), some niche formats might find a way to survive.

But that survival also likely will hinge on creation of new revenue and monetization mechanisms, as most bands now make their money from concerts, not selling pre-recorded music.

For programming “networks” (streaming services as well as broadcast TV or cable networks), survival might require expanded business models where the networks themselves are not required to generate high profits, but enable some other revenue model to to flourish. One thinks of Amazon Prime, where the revenue comes from memberships and higher e-commerce transaction volumes.

Streaming has not, so far, proven able to replace lost linear video losses. Whether that always will be the case is the issue.

E-commerce arguably has not led to a smaller retail industry, as much as it has reshaped the fortunes of legacy suppliers. But most would likely agree that newspaper/magazine (print) industry revenues are lower than before the online disruption.

The music industry might arguably also be smaller than before online music distribution. Whether video content follows the path of print media and music, or the pattern of retailing, is not yet clear.