As telcos have tried to "add value" to their services rather than "cut prices," so too video entertainment subscription providers will try to emphasize "more value" as an alternative to "cutting prices."

What remains to be seen is the success of such tactics, over time. At the moment, there doesn't seem to be much danger, though.

Since people buy "content," and since most of the popular content is not easily available online or over the top on the Internet, video subscriptions still have drawing power.

Monday Night Football is but one example of video content that remains exclusive to subscription services, The Hollywood Reporter reports.

Adding online and mobile content access as a form of added value for video subscribers likely will remain a major tactic, even as some operators mull launching lower cost services in some way, and possibly will do, at some point.

In the past, telcos have had mixed success trying to "add value" rather than "cut prices." In fact, you might argue, even over the top messaging and voice services that do provide added value mostly are valued because they represent lower-cost alternatives to traditional voice and messaging services.

But video is a different sort of product than "communications." The clearest example is the steady upward prices for video subscriptions every year, compared to declining nominal rates for communication services, or at least declining costs per unit.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Like Telcos, Cable Will Try to "Enhance Value" Rather than "Cut Price"

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Ofcom allows Everything Everywhere to use existing spectrum for 4G

Ofcom has today approved an application by the mobile phone operator Everything Everywhere to use its existing 1800 MHz spectrum to deliver 4G services, a move similar to what Ofcom in 2011 allowed in the transition from 2G to 3G.

Observers will note that the decision gives the largest U.K. mobile service provider a short window where it will be the only service provider to offer Long Term Evolution services in the United Kingdom, for a time.

The United Kingdom is required to make the 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum available for 4G use in light of a Decision of the European Commission, so the authorization is in line with the future 4G spectrum allocations.

The move gives Everything Everywhere a bit of a headstart in 4G services, of course, compared to other competitors that will have to wait until 4G spectrum auctions are completed.

Ofcom's decision means Everything Everywhere could, in principle, start offering Long Term Evolution services as early as Sept. 11, 2012, giving Everything Everywhere a market lead of perhaps a year or two over all the other providers of Long Term Evolution in the United Kingdom.

Observers will note that the decision gives the largest U.K. mobile service provider a short window where it will be the only service provider to offer Long Term Evolution services in the United Kingdom, for a time.

The United Kingdom is required to make the 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum available for 4G use in light of a Decision of the European Commission, so the authorization is in line with the future 4G spectrum allocations.

The move gives Everything Everywhere a bit of a headstart in 4G services, of course, compared to other competitors that will have to wait until 4G spectrum auctions are completed.

Ofcom's decision means Everything Everywhere could, in principle, start offering Long Term Evolution services as early as Sept. 11, 2012, giving Everything Everywhere a market lead of perhaps a year or two over all the other providers of Long Term Evolution in the United Kingdom.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

It's an "Untethered" World

A new study conducted by Cisco of more than a thousand U.S. mobile users suggests that the amount of Wi-Fi usage each day is so prevalent that smart phone, tablet and e-reader device usage now is more “nomadic” than mobile; more untethered than mobile; less “on the move” than just “unplugged.”

What’s more, the Cisco survey also suggests 25 percent of users “see no difference” between the mobile and Wi-Fi networks. The implied 75 percent of users who do see differences perhaps is the measure of the importance of voice communications and quick Internet operations or use of social networks and other communications apps.

At some point, such trends could lead to some specialized revenue models within the broader mobile and untethered access business, focusing purely on “data connections,” not mobile voice, much as the Wi-Fi hotspot business has been a specialized “data access” service.

That could ultimately be more important in developing regions where full mobile access is relatively expensive and bandwidth constrained, and might well rely on use of unlicensed spectrum and well as “self organizing” network nodes of some sort.

A separate study conducted by Ipsos suggests the typical employed person, in a wide range of countries, is connected to the Internet nearly 10 hours a day, often by Wi-Fi, with mobile devices used inside the home about 2.5 hours a day, as well.

All consumers use their mobile devices at home, the Cisco study found, averaging more than 2.5 hours of usage in a typical day, more than double the time that “mobile” devices are used “on the go,” which is about half an hour a day, the study also found.

A quarter of consumers surveyed by Cisco “see no difference” between the mobile and Wi-Fi networks. Consumers consider Wi-Fi easier to use and more reliable than mobile.

“We may be on the verge of a “New Mobile” paradigm, one in which Wi-Fi and mobile networks are seamlessly integrated and indistinguishable in the mobile user’s mind,” the Cisco study says.

Almost 60 percent of consumers were “somewhat” or “very” interested in a proposed offer that provides unlimited data across combined access networks for a flat monthly fee.

Separately, an Ipsos survey suggests people who work are connected to the Internet 9.8 hours a day, on average. That multi-country study surveyed users in in Argentina, Australia ,Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa ,South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the United States and Hong Kong. The detailed tables are here.

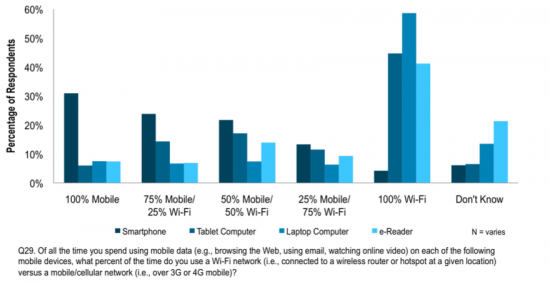

The survey conducted by Cisco’s Internet Business Solutions Group (IBSG) suggests

mobile users are connecting their devices predominantly using Wi-Fi. In fact, most mobile users are connecting their devices using Wi-Fi at some point, including 70 percent of smart phone owners.

About 50 percent of tablets, laptops, and e-readers are connecting exclusively through Wi-Fi. Although 30 percent of smartphone owners are connected only using the mobile network, the remaining 70 percent are supplementing mobile connectivity with Wi-Fi, the Cisco study suggests.

In fact, on average, smartphone users use Wi-Fi a third of the time to connect their devices to the Internet.

With the exception of smart phones, users would prefer to connect all of their devices usingWi-Fi. More than 80 percent of tablet, laptop, and e-reader owners either prefer Wi-Fi to mobile access or have no preference.

Just over half of smartphone owners would prefer to use Wi-Fi, or are ambivalent about the two access networks.

If given a choice between access networks, mobile users choose Wi-Fi over mobile across all network attributes, with the obvious exception of coverage. That leads Cisco researchers to conclude that “we may be on the verge of a ‘New Mobile’ paradigm, one in which Wi-Fi and mobile networks are seamlessly integrated and indistinguishable in the mobile user’s mind.”

Network Connectivity Type (by Time)

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2012

The Cisco research shows that 75 percent of Americans now have laptop computers, while 52 percent of respondents own smartphones, versus 48 percent who use traditional mobile phones.

Also, some 20 percent of Americans now own some kind of tablet, and 20 percent own an eReader.

With the exception of smart phones, Wi-Fi now is the predominant access technology for mobile devices. More “nomadic” devices like laptops, tablets, and e-readers almost exclusively connect to the Internet through Wi-Fi, with only approximately 20 percent of these devices having any mobile connectivity capability.

Device Network Connectivity (owned device)

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2012

Almost half of all mobile users regularly consume all forms of video, music, books, and games on their devices.

One of the insights is that while they may be called “mobile devices,” devices typically are used at home. All consumers use their mobile devices at home, averaging more than 2.5 hours of usage in a typical day, more than double the time that they spend using them at work.

While two thirds of people still use their devices on the go, the world of mobile devices is changing from a “mobile,” on-the-go world (average usage of 0.5 hours per typical day) to a “nomadic” world dominated by the home. And, people expect to increase their home use of mobile devices even more.

Cisco IBSG conducted its online study of 1,079 U.S mobile users in March 2012. The study was also undertaken in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, and the United Kingdom.

What’s more, the Cisco survey also suggests 25 percent of users “see no difference” between the mobile and Wi-Fi networks. The implied 75 percent of users who do see differences perhaps is the measure of the importance of voice communications and quick Internet operations or use of social networks and other communications apps.

At some point, such trends could lead to some specialized revenue models within the broader mobile and untethered access business, focusing purely on “data connections,” not mobile voice, much as the Wi-Fi hotspot business has been a specialized “data access” service.

That could ultimately be more important in developing regions where full mobile access is relatively expensive and bandwidth constrained, and might well rely on use of unlicensed spectrum and well as “self organizing” network nodes of some sort.

A separate study conducted by Ipsos suggests the typical employed person, in a wide range of countries, is connected to the Internet nearly 10 hours a day, often by Wi-Fi, with mobile devices used inside the home about 2.5 hours a day, as well.

All consumers use their mobile devices at home, the Cisco study found, averaging more than 2.5 hours of usage in a typical day, more than double the time that “mobile” devices are used “on the go,” which is about half an hour a day, the study also found.

A quarter of consumers surveyed by Cisco “see no difference” between the mobile and Wi-Fi networks. Consumers consider Wi-Fi easier to use and more reliable than mobile.

“We may be on the verge of a “New Mobile” paradigm, one in which Wi-Fi and mobile networks are seamlessly integrated and indistinguishable in the mobile user’s mind,” the Cisco study says.

Almost 60 percent of consumers were “somewhat” or “very” interested in a proposed offer that provides unlimited data across combined access networks for a flat monthly fee.

Separately, an Ipsos survey suggests people who work are connected to the Internet 9.8 hours a day, on average. That multi-country study surveyed users in in Argentina, Australia ,Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa ,South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the United States and Hong Kong. The detailed tables are here.

The survey conducted by Cisco’s Internet Business Solutions Group (IBSG) suggests

mobile users are connecting their devices predominantly using Wi-Fi. In fact, most mobile users are connecting their devices using Wi-Fi at some point, including 70 percent of smart phone owners.

About 50 percent of tablets, laptops, and e-readers are connecting exclusively through Wi-Fi. Although 30 percent of smartphone owners are connected only using the mobile network, the remaining 70 percent are supplementing mobile connectivity with Wi-Fi, the Cisco study suggests.

In fact, on average, smartphone users use Wi-Fi a third of the time to connect their devices to the Internet.

With the exception of smart phones, users would prefer to connect all of their devices usingWi-Fi. More than 80 percent of tablet, laptop, and e-reader owners either prefer Wi-Fi to mobile access or have no preference.

Just over half of smartphone owners would prefer to use Wi-Fi, or are ambivalent about the two access networks.

If given a choice between access networks, mobile users choose Wi-Fi over mobile across all network attributes, with the obvious exception of coverage. That leads Cisco researchers to conclude that “we may be on the verge of a ‘New Mobile’ paradigm, one in which Wi-Fi and mobile networks are seamlessly integrated and indistinguishable in the mobile user’s mind.”

Network Connectivity Type (by Time)

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2012

The Cisco research shows that 75 percent of Americans now have laptop computers, while 52 percent of respondents own smartphones, versus 48 percent who use traditional mobile phones.

Also, some 20 percent of Americans now own some kind of tablet, and 20 percent own an eReader.

With the exception of smart phones, Wi-Fi now is the predominant access technology for mobile devices. More “nomadic” devices like laptops, tablets, and e-readers almost exclusively connect to the Internet through Wi-Fi, with only approximately 20 percent of these devices having any mobile connectivity capability.

Device Network Connectivity (owned device)

Source: Cisco IBSG, 2012

Almost half of all mobile users regularly consume all forms of video, music, books, and games on their devices.

One of the insights is that while they may be called “mobile devices,” devices typically are used at home. All consumers use their mobile devices at home, averaging more than 2.5 hours of usage in a typical day, more than double the time that they spend using them at work.

While two thirds of people still use their devices on the go, the world of mobile devices is changing from a “mobile,” on-the-go world (average usage of 0.5 hours per typical day) to a “nomadic” world dominated by the home. And, people expect to increase their home use of mobile devices even more.

Cisco IBSG conducted its online study of 1,079 U.S mobile users in March 2012. The study was also undertaken in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, and the United Kingdom.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Monday, August 20, 2012

Will Fixed Network Voice Connections Drop to Zero?

The latest report on U.S. fixed network voice connections by the Federal Communications Commission suggests that voice connections declined three percent between June 2010 and June 2011. That raises an obvious question: will number of fixed voice connections continue to drop, without end, to zero?

That seems highly improbable. There would seem to be some good reasons for predicting a perpetual demand for fixed voice connections, not the least of which is that voice quality likely always will be higher, and more consistent, on fixed connections, compared to mobile or forms of VoIP that do not use managed connections.

But that isn’t the only reason. Much might hinge on how voice services are packaged and priced.

In principle, service providers can package fixed network voice service in ways that impose little incremental cost over not buying the service, or in fact tie the purchase of another network service to the voice service. That is not to discount the “add value” approaches, but simply to note that the easiest path forward is simply to make fixed voice service so affordable there is no reason to drop it.

Service providers will not like the gross revenue implications, but the simple matter is that if the value of fixed voice keeps dropping, compared to mobile voice, erosion will continue. On the other hand, if voice and perhaps other features are bundled with the “lead” broadband access service in ways that users find reasonable, massive erosion might be avoided.

Under the new Verizon Wireless pricing scheme, for example, though users can still use over the top messaging and voice, there is no financial incentive to do so, at least for domestic calling.

At some point, fixed network providers will probably reach the same conclusion, and package “broadband access” with voice features in ways that make paying for fixed network voice a reasonable and preferable option. You might argue that Charter Communications and Verizon’s landline business already have moved in that direction.

A new policy by Charter, and the Verizon “Share Everything” plans simply make voice a feature of a broadband service.

Charter is going to stop selling voice subscriptions as a discrete product, and will in the future only sell voice in conjunction with at least one other service, either entertainment video or broadband access.

Verizon, for its part, also requires bundling of a voice line with DSL. Charter is adopting similar policies.

"Going forward, we will not offer Charter Phone as a standalone product," a Charter spokesman apparently has confirmed.

source: Allied Telesis

In principle, the bundling is akin to the ways consumers buy many other products. When you buy a PC, a tablet, a smart phone, an iPod or an automobile, you get a battery as part of the device. Both Charter and Verizon Wireless now are making “voice” part of a product bundle, a feature, essentially.

If, as some of us suspect, voice and messaging eventually will be features of a network access service, then the number of voice “lines” in service will stop falling, in line either with the number of broadband access or video entertainment accounts in service.

The point is that landline voice accounts will not decline, without end, even if consumer prefer to use mobile voice, so long as retail policies tie the use of other valued network services to a bundle that includes a voice service.

That seems highly improbable. There would seem to be some good reasons for predicting a perpetual demand for fixed voice connections, not the least of which is that voice quality likely always will be higher, and more consistent, on fixed connections, compared to mobile or forms of VoIP that do not use managed connections.

But that isn’t the only reason. Much might hinge on how voice services are packaged and priced.

In principle, service providers can package fixed network voice service in ways that impose little incremental cost over not buying the service, or in fact tie the purchase of another network service to the voice service. That is not to discount the “add value” approaches, but simply to note that the easiest path forward is simply to make fixed voice service so affordable there is no reason to drop it.

Service providers will not like the gross revenue implications, but the simple matter is that if the value of fixed voice keeps dropping, compared to mobile voice, erosion will continue. On the other hand, if voice and perhaps other features are bundled with the “lead” broadband access service in ways that users find reasonable, massive erosion might be avoided.

Under the new Verizon Wireless pricing scheme, for example, though users can still use over the top messaging and voice, there is no financial incentive to do so, at least for domestic calling.

At some point, fixed network providers will probably reach the same conclusion, and package “broadband access” with voice features in ways that make paying for fixed network voice a reasonable and preferable option. You might argue that Charter Communications and Verizon’s landline business already have moved in that direction.

A new policy by Charter, and the Verizon “Share Everything” plans simply make voice a feature of a broadband service.

Charter is going to stop selling voice subscriptions as a discrete product, and will in the future only sell voice in conjunction with at least one other service, either entertainment video or broadband access.

Verizon, for its part, also requires bundling of a voice line with DSL. Charter is adopting similar policies.

"Going forward, we will not offer Charter Phone as a standalone product," a Charter spokesman apparently has confirmed.

source: Allied Telesis

In principle, the bundling is akin to the ways consumers buy many other products. When you buy a PC, a tablet, a smart phone, an iPod or an automobile, you get a battery as part of the device. Both Charter and Verizon Wireless now are making “voice” part of a product bundle, a feature, essentially.

If, as some of us suspect, voice and messaging eventually will be features of a network access service, then the number of voice “lines” in service will stop falling, in line either with the number of broadband access or video entertainment accounts in service.

The point is that landline voice accounts will not decline, without end, even if consumer prefer to use mobile voice, so long as retail policies tie the use of other valued network services to a bundle that includes a voice service.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

No Digital Divide?

One doesn’t hear quite so much about “digital divides” as was common a decade ago. One suspects that is because the supply of communications, both voice and data, is a problem the world seems capable of solving.

Some of us can remember great "handwringing" an concern in international policy circles about how to bring telephone service to two billion people who never had made a phone call. You don't hear such concern anymore, since we rapidly are solving that problem with mobile communications, a solution not envisioned in the 1970s and 1980s.

Two decades ago the question largely had shifted to the problem of how to get computing into the hands of the next three billion people. There was some work around the notion of special devices optimized for rural villagers that would be low cost, perhaps $150 or so.

For many at the time, likely most knowledgeable observers, the prevailing thinking was that it couldn't really be done. And that remained true even as recently as the middle of the 2000 decade.

But as we stumbled upon a solution to the problem of getting communications to people at prices they could afford, we are about to solve the problem of getting computers to people, also at prices they can afford.

The notion, for some time, has been that in many parts of the world, the smart phone would be "the computer" most people used. That might turn out to be largely correct, for at least a time.

But it also now is possible that we know how to create and sell computers to people that cost no more than $150. Consider that the prototype "One Laptop Per Child" device had a screen of 7.5 inches diagonal and flash memory, with no keyboard.and used Wi-Fi for Internet connectivity.

Oh, that's right, we now call that a tablet, and it is made and sold commercially by the likes of Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and soon Google and likely Apple.

One might note a similar process at work even in the area of rural broadband access. Does it make sense to spend up to $50,000 per home to provide broadband access service to less than 200,000 U.S. rural locations, when at least two other approaches are already available?

The Federal Communications Commission, for example, conducted a gap analysis that suggested $13.4 billion in subsidies would be required to expand availability to only 250,000 of the highest cost homes (0.19 percent of all U.S. homes).

According to the FCC, those homes would require subsidies of about $53,600 – on top of what service providers would expect to spend to connect a typical home.

Excluding the cost of serving these 250,000 homes, the cost of connecting the remaining 6.75 million homes would entail a subsidy of about $1,500 per home passed.

Keep in mind that the “broadband gap” affects less than five percent of U.S. homes. The Federal Communications Commission itself estimates that seven million U.S. households do not have access to terrestrial broadband service, representing about 5.4 percent of the 129 million U.S. homes.

Additionally, analysis assumes those households actually are occupied, but they are not. Some percentage is unoccupied, and some are used only partly as vacation homes.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 18 million of the 130 million units are not occupied (about 14 percent).

On average, the gap estimated by the Commission is $3,357 per home passed, note Dr. George Ford, Phoenix Center chief economist, and Lawrence J. Spiwak, Phoenix Center president.

Even the then director of the National Broadband Plan, Blair Levin, said it will be too expensive to provide service to the last two percent of home using terrestrial facilities. Therefore, those homes should be served by satellite broadband.

A more reasonable approach to satellite broadband at the time might have been that if it costs $50,000 to provide a 4:1 Mbps terrestrial broadband service to a household, then is it reasonable to accept a “lower” service level by a network that already reaches those locations?

The situation has also changed since that analysis. ViaSat’s “Exede” satellite broadband service already has been offering speeds up to 12 Mbps downstream and up to 3 Mbps upstream, for $50 per month, since early 2012.

The HughesNet service, which has launched a new satellite of its own, will begin offering faster service beginning this month. Since both the ViaSat and HughesNet services use exactly the same satellites, it would be reasonable to assume that HughesNet will offer speeds comparable to that of Exede.

In fact, the National Broadband Plan explicitly recognized that the cost of ubiquitous coverage of terrestrial broadband could not be justified and furthermore recommended the use of “satellite broadband” as an alternative, as it is ubiquitously available, Phoenix Center argues.

The cost picture has changed dramatically since the FCC conducted its gap analysis. Though the original plan called for a 4 Mbps capability, Exede already sells a 12-Mbps service for $50 a month. As of Aug. 13, 2012, Hughesnet has not announced firm pricing and speeds.

But there is no reason to believe HughesNet will offer speeds any less than offered by Exede. The point is that by spending an abundance of money, the government simply does not make sense at the margin.

The point is that one has to be careful about interpreting Internet or broadband usage trends. In past years, some observers have argued there is a significant “digital divide,” using statistics about Internet or broadband usage (people who buy and use that product or capability) rather than broadband or Internet “availability” (the service actually is available to purchase).

A decade ago, access mostly was measured by activity occurring only on the fixed networks, as well.

The point is that the difference between whether a product is available, and whether a consumer chooses to buy it, is highly significant. A “digital divide” argument assumes that a product such as broadband access is statistically “unavailable,” meaning there is an “access to the product” problem. Lower availability in rural or sparsely-populated areas is one form of the argument.

The latest study of mobile broadband behavior shows the relevance of the distinction between “available to buy” and “I want to buy it.”

About 17 percent of mobile phone owners do most of their online browsing on their phone, rather than a computer or other device, the Pew Center Internet & American Life Project reports.

Young adults and non-whites are especially likely to use their mobile phones for the majority of their online activity, the researchers say.

Nearly half of all 18 to 29 year olds (45 percent) who use the Internet on their mobile phones do most of their online browsing on their mobile device, the study found.

Half (51 percent) of African-American mobile Internet users do most of their online browsing on their phone, double the proportion for whites (24 percent). Two in five Latino cell internet users (42 percent) also fall into the “cell-mostly” category.

Digital marketing specialist Troy Brown, president of one50one thinks Hispanics generate 50 percent of their Internet traffic from mobile phones.

The important implications here are that people might prefer to use mobile Internet and mobile broadband, rather than fixed access, in numbers that are significant.

Additionally, those with an annual household income of less than $50,000 per year and those who have not graduated college are more likely than those with higher levels of income and education to use their phones for most of their online browsing, Pew researchers say.

In that sense, the adoption of mobile broadband might be a rational choice, similar to adoption of mobile “as voice,” when people choose to use a mobile exclusively for their voice service. In fact, we might already have reached the point where further growth of fixed network broadband connections is limited or slowed because users have better mobile alternatives.

The Pew data also suggests that mobile broadband has been particularly important to populations that in the past have “under-indexed” for use of fixed network broadband. The point is that, aside from buyer preferences being at play, fixed network broadband purchases increasingly are not suitable measures of “broadband adoption.”

When 17 percent of mobile users report “mostly” using their mobiles for Internet access, any metrics of adoption that ignore mobile access will be misleading.

On a larger level, one might make the argument that the digital divide, and the communications divide, simply are problems we are solving.

Some of us can remember great "handwringing" an concern in international policy circles about how to bring telephone service to two billion people who never had made a phone call. You don't hear such concern anymore, since we rapidly are solving that problem with mobile communications, a solution not envisioned in the 1970s and 1980s.

Two decades ago the question largely had shifted to the problem of how to get computing into the hands of the next three billion people. There was some work around the notion of special devices optimized for rural villagers that would be low cost, perhaps $150 or so.

For many at the time, likely most knowledgeable observers, the prevailing thinking was that it couldn't really be done. And that remained true even as recently as the middle of the 2000 decade.

But as we stumbled upon a solution to the problem of getting communications to people at prices they could afford, we are about to solve the problem of getting computers to people, also at prices they can afford.

The notion, for some time, has been that in many parts of the world, the smart phone would be "the computer" most people used. That might turn out to be largely correct, for at least a time.

But it also now is possible that we know how to create and sell computers to people that cost no more than $150. Consider that the prototype "One Laptop Per Child" device had a screen of 7.5 inches diagonal and flash memory, with no keyboard.and used Wi-Fi for Internet connectivity.

Oh, that's right, we now call that a tablet, and it is made and sold commercially by the likes of Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and soon Google and likely Apple.

One might note a similar process at work even in the area of rural broadband access. Does it make sense to spend up to $50,000 per home to provide broadband access service to less than 200,000 U.S. rural locations, when at least two other approaches are already available?

The Federal Communications Commission, for example, conducted a gap analysis that suggested $13.4 billion in subsidies would be required to expand availability to only 250,000 of the highest cost homes (0.19 percent of all U.S. homes).

According to the FCC, those homes would require subsidies of about $53,600 – on top of what service providers would expect to spend to connect a typical home.

Excluding the cost of serving these 250,000 homes, the cost of connecting the remaining 6.75 million homes would entail a subsidy of about $1,500 per home passed.

Keep in mind that the “broadband gap” affects less than five percent of U.S. homes. The Federal Communications Commission itself estimates that seven million U.S. households do not have access to terrestrial broadband service, representing about 5.4 percent of the 129 million U.S. homes.

Additionally, analysis assumes those households actually are occupied, but they are not. Some percentage is unoccupied, and some are used only partly as vacation homes.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 18 million of the 130 million units are not occupied (about 14 percent).

On average, the gap estimated by the Commission is $3,357 per home passed, note Dr. George Ford, Phoenix Center chief economist, and Lawrence J. Spiwak, Phoenix Center president.

Even the then director of the National Broadband Plan, Blair Levin, said it will be too expensive to provide service to the last two percent of home using terrestrial facilities. Therefore, those homes should be served by satellite broadband.

A more reasonable approach to satellite broadband at the time might have been that if it costs $50,000 to provide a 4:1 Mbps terrestrial broadband service to a household, then is it reasonable to accept a “lower” service level by a network that already reaches those locations?

The situation has also changed since that analysis. ViaSat’s “Exede” satellite broadband service already has been offering speeds up to 12 Mbps downstream and up to 3 Mbps upstream, for $50 per month, since early 2012.

The HughesNet service, which has launched a new satellite of its own, will begin offering faster service beginning this month. Since both the ViaSat and HughesNet services use exactly the same satellites, it would be reasonable to assume that HughesNet will offer speeds comparable to that of Exede.

In fact, the National Broadband Plan explicitly recognized that the cost of ubiquitous coverage of terrestrial broadband could not be justified and furthermore recommended the use of “satellite broadband” as an alternative, as it is ubiquitously available, Phoenix Center argues.

The cost picture has changed dramatically since the FCC conducted its gap analysis. Though the original plan called for a 4 Mbps capability, Exede already sells a 12-Mbps service for $50 a month. As of Aug. 13, 2012, Hughesnet has not announced firm pricing and speeds.

But there is no reason to believe HughesNet will offer speeds any less than offered by Exede. The point is that by spending an abundance of money, the government simply does not make sense at the margin.

The point is that one has to be careful about interpreting Internet or broadband usage trends. In past years, some observers have argued there is a significant “digital divide,” using statistics about Internet or broadband usage (people who buy and use that product or capability) rather than broadband or Internet “availability” (the service actually is available to purchase).

A decade ago, access mostly was measured by activity occurring only on the fixed networks, as well.

The point is that the difference between whether a product is available, and whether a consumer chooses to buy it, is highly significant. A “digital divide” argument assumes that a product such as broadband access is statistically “unavailable,” meaning there is an “access to the product” problem. Lower availability in rural or sparsely-populated areas is one form of the argument.

The latest study of mobile broadband behavior shows the relevance of the distinction between “available to buy” and “I want to buy it.”

About 17 percent of mobile phone owners do most of their online browsing on their phone, rather than a computer or other device, the Pew Center Internet & American Life Project reports.

Young adults and non-whites are especially likely to use their mobile phones for the majority of their online activity, the researchers say.

Nearly half of all 18 to 29 year olds (45 percent) who use the Internet on their mobile phones do most of their online browsing on their mobile device, the study found.

Half (51 percent) of African-American mobile Internet users do most of their online browsing on their phone, double the proportion for whites (24 percent). Two in five Latino cell internet users (42 percent) also fall into the “cell-mostly” category.

Digital marketing specialist Troy Brown, president of one50one thinks Hispanics generate 50 percent of their Internet traffic from mobile phones.

The important implications here are that people might prefer to use mobile Internet and mobile broadband, rather than fixed access, in numbers that are significant.

Additionally, those with an annual household income of less than $50,000 per year and those who have not graduated college are more likely than those with higher levels of income and education to use their phones for most of their online browsing, Pew researchers say.

In that sense, the adoption of mobile broadband might be a rational choice, similar to adoption of mobile “as voice,” when people choose to use a mobile exclusively for their voice service. In fact, we might already have reached the point where further growth of fixed network broadband connections is limited or slowed because users have better mobile alternatives.

The Pew data also suggests that mobile broadband has been particularly important to populations that in the past have “under-indexed” for use of fixed network broadband. The point is that, aside from buyer preferences being at play, fixed network broadband purchases increasingly are not suitable measures of “broadband adoption.”

When 17 percent of mobile users report “mostly” using their mobiles for Internet access, any metrics of adoption that ignore mobile access will be misleading.

On a larger level, one might make the argument that the digital divide, and the communications divide, simply are problems we are solving.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

O2 Customers Talk 12 Minutes a Day

On average, U.K. mobile service provider O2 has found, smart phone owners now spend over two hours a day using their devices, but talk only 12 minutes, and text only 10 minutes.

Smart phone users spend more time browsing the internet (25 minutes a day), social networking (17 minutes a day), playing games (13 minutes a day) and listening to music (16 minutes a day) than they do making calls (12 minutes), O2 says.

That illustrates the multi-function nature of smart phones, as well as the key role smart phones now play in a full range of "Internet access" activities.

Checking or writing emails represents 11 minutes of activity a day. Watching video consumes 9.4 minutes a day, while reading books represents about 9.3 minutes a day.

People spend about 3.4 minutes a day tacking pictures, as well.

For many people, the smartphone is replacing other possessions including alarm clocks, watches, cameras, diaries and even laptops and TVs as they become more intuitive and easier to use for things “beyond calls”.

Smart phone users spend more time browsing the internet (25 minutes a day), social networking (17 minutes a day), playing games (13 minutes a day) and listening to music (16 minutes a day) than they do making calls (12 minutes), O2 says.

That illustrates the multi-function nature of smart phones, as well as the key role smart phones now play in a full range of "Internet access" activities.

Checking or writing emails represents 11 minutes of activity a day. Watching video consumes 9.4 minutes a day, while reading books represents about 9.3 minutes a day.

People spend about 3.4 minutes a day tacking pictures, as well.

For many people, the smartphone is replacing other possessions including alarm clocks, watches, cameras, diaries and even laptops and TVs as they become more intuitive and easier to use for things “beyond calls”.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

"How to Compete" with Over the Top is a Key Mobile Service Provider Issue

Some would argue that a war over “interpersonal communications,” separate from the earlier messaging formats of email, instant messaging, chat and text messaging, is about to break out among three of the over the top application platforms, namely Google, Facebook and Apple.

For mobile service providers, that poses an issue, namely the future of their text messaging revenue streams, since historically mobile service providers have not make money directly from email or chat.

Facebook’s unified Chat / Messages / Email; Apple’s cross-device iMessage system and Google’s Gmail / GChat / Hangouts are something different,some would argue, as those platforms blend email, messaging chat and even video conferencing.

For mobile service providers, “how to compete” is the issue. A reasonable person might argue that no mobile service provider is fully equipped to compete in the “interpersonal communications” space dominated by those three application providers.

But every mobile service provider has an indirect interest in all those applications. Email was the killer app that drove adoption of dial-up Internet services. BlackBerry made mobile access to email a revenue driver for mobile data plans.

Messaging remains a pillar of the emerging “interpersonal communications” business, and incorporates the value of text messaging, which is the direct revenue stream mobile service providers have dominated.

Chat traditionally has been a feature users have valued as part of social networking platforms, and many would argue that mobile use of social networks is a key part of the value proposition for buying a mobile data plan.

At some level, then, sales of mobile data plans will be a direct benefit mobile service providers can expect, no matter which messaging platform “wins.”

On the other hand, SMS revenues could suffer if users start to migrate their short message activities to one or more of the application platforms.

Some of us would argue that among the advantages of the new Verizon Wireless “Share Everything” service plans is the ability to preserve much of the value and revenue once provided by discrete voice and text messaging plans, even as users migrate to the newer “interpersonal communications” platforms.

Others will argue that mobile service providers have to jump into the over the top voice and messaging business on a branded basis.

Over the top mobile voice and texting apps now affect traffic for almost 75 percent of mobile service providers operating in 68 countries surveyed by mobileSquared as part of a project sponsored by Tyntec.

But the potential danger will vary from country to country. Service providers in smaller countries, where lots of cross-border calling or messaging occurs, with high tariffs for cross-border traffic, will experience more danger than large countries with larger internal populations that can call quite some distance without crossing a border.

OTT apps and services also will cannibalize international calling revenues in any country with a large migrant population outside the home country. Think Filipinos working in the Middle East, or Indians living in the United States.

Likewise, mobile service providers might be able to create a mediating role that bridges a closed OTT community by enabling third party access to some other third party community using the mobile phone number.

For mobile service providers, that poses an issue, namely the future of their text messaging revenue streams, since historically mobile service providers have not make money directly from email or chat.

Facebook’s unified Chat / Messages / Email; Apple’s cross-device iMessage system and Google’s Gmail / GChat / Hangouts are something different,some would argue, as those platforms blend email, messaging chat and even video conferencing.

For mobile service providers, “how to compete” is the issue. A reasonable person might argue that no mobile service provider is fully equipped to compete in the “interpersonal communications” space dominated by those three application providers.

But every mobile service provider has an indirect interest in all those applications. Email was the killer app that drove adoption of dial-up Internet services. BlackBerry made mobile access to email a revenue driver for mobile data plans.

Messaging remains a pillar of the emerging “interpersonal communications” business, and incorporates the value of text messaging, which is the direct revenue stream mobile service providers have dominated.

Chat traditionally has been a feature users have valued as part of social networking platforms, and many would argue that mobile use of social networks is a key part of the value proposition for buying a mobile data plan.

At some level, then, sales of mobile data plans will be a direct benefit mobile service providers can expect, no matter which messaging platform “wins.”

On the other hand, SMS revenues could suffer if users start to migrate their short message activities to one or more of the application platforms.

Some of us would argue that among the advantages of the new Verizon Wireless “Share Everything” service plans is the ability to preserve much of the value and revenue once provided by discrete voice and text messaging plans, even as users migrate to the newer “interpersonal communications” platforms.

Others will argue that mobile service providers have to jump into the over the top voice and messaging business on a branded basis.

Over the top mobile voice and texting apps now affect traffic for almost 75 percent of mobile service providers operating in 68 countries surveyed by mobileSquared as part of a project sponsored by Tyntec.

But the potential danger will vary from country to country. Service providers in smaller countries, where lots of cross-border calling or messaging occurs, with high tariffs for cross-border traffic, will experience more danger than large countries with larger internal populations that can call quite some distance without crossing a border.

OTT apps and services also will cannibalize international calling revenues in any country with a large migrant population outside the home country. Think Filipinos working in the Middle East, or Indians living in the United States.

On the other hand, retail packaging can alleviate some of the potential risk, as Verizon Wireless is doing with its "Share Everything" plans.

About 52.1 percent of respondents estimate over the top mobile apps have displaced about one percent to 20 percent of traffic in 2012. That’s a clear issue since traffic lost means lost revenue as well.

Almost 33 percent of respondents expect one percent to 10 percent of their customers will

be using OTT services by the end of 2012, with 57 percent of respondents believe 11 percent to 40 percent of their customers will be using OTT services in 2012.

But 10.5 percent of service providers anticipate more than 40 percent of the user base will be using OTT services by the end of 2012.

In 2016, 100 percent of respondents believe at least 11 percent of their customers will be using OTT services. In fact, 42 percent of operators believe that over 40 percent of their customer base will be using OTT services in 2016.

The issue is what to do about the threat. In some countries, it might be legal for mobile operators to block use of OTT apps, as some carriers blocked use of VoIP. You can make your own judgment about whether that is a long-term possibility.

There are direct and indirect ways to respond, though. It is at least conceivable that some mobile service providers can legally create separate fees for consumer use of over the top voice and messaging apps. In other cases service providers will have to recapture some of the lost revenue by increasing mobile data charges in some way.

Verizon Wireless protects its voice and texting revenue streams by essentially changing voice and texting services into the equivalent of a connection fee to use the network. Verizon charges a flat monthly fee for unlimited domestic voice and texting.

The harder questions revolve around whether any service provider should create its own OTT voice and messaging apps, even if those apps compete with carrier services. Aside from potentially cannibalizing carrier voice and data services, this approach arguably does take some share from rival OTT providers.

On the other hand, it is a defensive approach that essentially concedes declining revenue, with some amount of ability to capture revenue in the “OTT voice and messaging” space.

Some larger service providers might find they are able to consider a partnering strategy with leading OTT players. To some extent, this also is a defensive move aimed at recouping some lost voice and messaging revenues. In other words, if a customer is determined to switch to OTT voice and data, the revenue from such usage ought to flow to the mobile service provider, if possible.

But there is a notable difference to the branded carrier OTT app approach. In principle, such OTT apps can be a way of extending a brand’s service footprint outside its historic licensed areas, into countries where it is not currently licensed.

Instead of functioning as a defensive tactic that recoups some share of OTT revenue in territory, OTT voice and messaging can be viewed as an offensive way of providing voice and messaging services out of region, says Thorsten Trapp, Tyntec CTO.

Over the longer term, it might also be possible for mobile service providers to replicate the network effect that makes today’s voice and messaging so appealing, namely the ability to contact anybody with a phone, anywhere, without having to worry about whether the contacted party is “on the network” or “in the community” or not. The RCS-e/Joyn effort is an example of that approach.

Likewise, mobile service providers might be able to create a mediating role that bridges a closed OTT community by enabling third party access to some other third party community using the mobile phone number.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

On the Use and Misuse of Principles, Theorems and Concepts

When financial commentators compile lists of "potential black swans," they misunderstand the concept. As explained by Taleb Nasim ...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...