Some have argued that mobile VoIP will grow mobile service provider revenues, an argument that makes more sense if one assumes the mobile VoIP is provided by a third party “over the top,” or by a new entrant without a significant legacy customer base.

In most other cases, a rational person would argue that mobile VoIP is more likely to harm mobile service provider revenues. Mobile VoIP might represent less than 0.5 percent of overall service provider mobile voice revenues, according to ARCchart.

ARCchart sees similar issues for mobile service provider messaging. ARCchart expects that instant messages will exceed text messaging volumes by 2014 and continue growing rapidly, accounting for 65 percent of all message traffic pushed over mobile networks by 2016.

In 2012, global mobile VoIP service revenues might be about $2.5 billion. But mobile voice revenue overall could be in the range of roughly $1 trillion.

So the problem is that mobile VoIP represents a very small percentage of the legacy mobile voice revenue stream. To be sure, mobile VoIP is in its early stages, so a direct comparison of revenue means very little. So far, mobile VoIP probably has been important mostly as it reflects the loss of high-margin and high volume legacy voice call volumes.

But that is not likely to be the case, always. There will be 1.1 billion mobile VoIP clients in use by 2017, over half of which will be over the top apps, analysts at Juniper Research now estimate. Just how much revenue those mobile VoIP users will generate is the issue.

"As with Skype on the desktop, only a very small proportion will pay for the service," Juniper Research said. “Wi-Fi mobile VoIP is potentially the most damaging of all VoIP traffic, as it bypasses the mobile networks altogether."

“We forecast that mobile VoIP over Wi-Fi will cost operators $5 billion globally by 2015,” said Anthony Cox, Juniper Research analyst.

In fact, a recent forecast by Visiongain suggests 2012 mobile VoIP revenues would reach only about $2.5 billion to $4 billion, globally.

“Many subscribers sign up to an OTT service without ever planning to pay a cent for it, and some industry players do not have a short-term revenue model at all,” said Cox.

Still, researchers at Analysys have in the past predicted that, as early as 2012, mobile VoIP services would generate revenues of $18.6 billion (EUR15.3 billion) in the United States and $7.3 billion (EUR.6.0 billion) in Western Europe, compared with fixed VoIP revenues of $11.9 (EUR9.8 billion) in the United States and $6.9 billion (EUR5.7 billion) in Western Europe.

It seems doubtful those levels of revenue have been realized, though. In fact, analysts seem to have overestimated the revenue mobile VoIP would represent, rather consistently. Though service providers are not without options, the direction is clear. As one self-proclaimed optimist said recently, “voice isn’t dead yet.” And that’s the optimistic view.

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

"Voice Isn't Dead Yet," Optimist Says

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

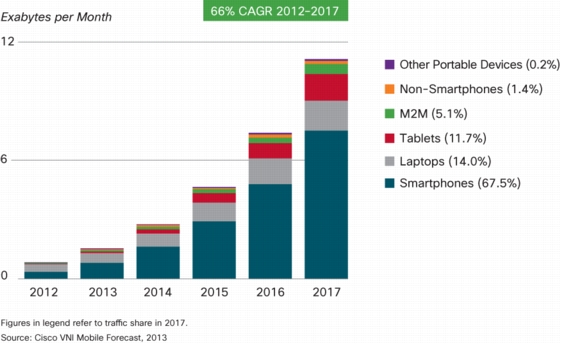

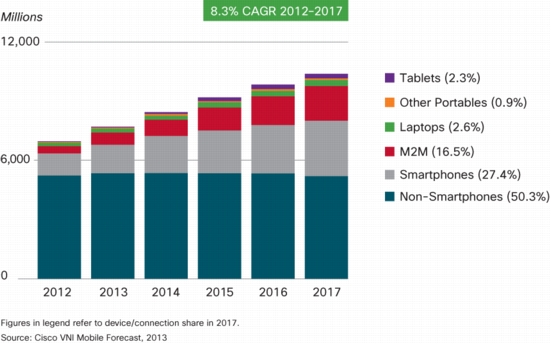

Smart Phones Drive Mobile Data Consumption, Globally

In 2012, global mobile data traffic grew more than 70 percent year over year, to 855 petabytes a month, according to Cisco.

Mobile data traffic growth varied by region, with the slowest growth experienced by Western Europe at 44 percent, and the highest growth rates experienced by Middle East and Africa (101 percent) and Asia Pacific (95 percent).

There are three key reasons for the lower mobile data traffic growth in Europe in 2012, Cisco says. Tiered mobile data packages are one reason, as most “unlimited” plans have been eliminated.

In Europe, there also has been a slowdown in the number of mobile-connected laptop net additions. The number of mobile-connected laptops in Europe declined from 33.8 million at the end of 2011 to 32.6 million at the end of 2012.

In Europe, there also has been an increase in the amount of mobile traffic offloaded to the fixed network. Operators have encouraged the offload of traffic onto Wi-Fi networks. Tablet traffic

that might have migrated to mobile networks has largely remained on fixed networks, as well.

By 2017, global mobile data traffic will reach 11.2 exabytes per month, or a run rate of 134 exabytes annually.

Smart phones will be 68 percent of total mobile data traffic in 2017, compared to 44 percent in 2012. LTE 4G connections will be 10 percent of total mobile connections in 2017, and 45 percent of mobile data traffic.

Global mobile network connection speeds doubled in 2012 and will increase seven fold by 2017, reaching 3.9 Mbps.

As much as 46 percent of global mobile data traffic will be offloaded in 2017, up from 33 percent in 2012, Cisco forecasts.

By 2017, 66 percent of the world’s mobile data traffic will be video, up from 51 percent in 2012.

The Middle East and Africa will have the strongest mobile data traffic growth of any region at 104 percent compound annual growth rates, followed by Asia Pacific at 84 percent and Central and Eastern Europe at 83 percent.

Mobile data traffic growth varied by region, with the slowest growth experienced by Western Europe at 44 percent, and the highest growth rates experienced by Middle East and Africa (101 percent) and Asia Pacific (95 percent).

There are three key reasons for the lower mobile data traffic growth in Europe in 2012, Cisco says. Tiered mobile data packages are one reason, as most “unlimited” plans have been eliminated.

In Europe, there also has been a slowdown in the number of mobile-connected laptop net additions. The number of mobile-connected laptops in Europe declined from 33.8 million at the end of 2011 to 32.6 million at the end of 2012.

Per Device Usage, MByes per Month

Device Type

|

2012

|

2017

|

Non smart phone

|

6.8

|

31

|

M2M Module

|

64

|

330

|

Smart phone

|

342

|

2,660

|

4G Smart phone

|

1,302

|

5,114

|

Tablet

|

820

|

5,387

|

Laptop

|

2,503

|

5,731

|

In Europe, there also has been an increase in the amount of mobile traffic offloaded to the fixed network. Operators have encouraged the offload of traffic onto Wi-Fi networks. Tablet traffic

that might have migrated to mobile networks has largely remained on fixed networks, as well.

By 2017, global mobile data traffic will reach 11.2 exabytes per month, or a run rate of 134 exabytes annually.

Smart phones will be 68 percent of total mobile data traffic in 2017, compared to 44 percent in 2012. LTE 4G connections will be 10 percent of total mobile connections in 2017, and 45 percent of mobile data traffic.

Global mobile network connection speeds doubled in 2012 and will increase seven fold by 2017, reaching 3.9 Mbps.

As much as 46 percent of global mobile data traffic will be offloaded in 2017, up from 33 percent in 2012, Cisco forecasts.

By 2017, 66 percent of the world’s mobile data traffic will be video, up from 51 percent in 2012.

The Middle East and Africa will have the strongest mobile data traffic growth of any region at 104 percent compound annual growth rates, followed by Asia Pacific at 84 percent and Central and Eastern Europe at 83 percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

U.K. Regulator to Allow LTE in all Mobile Frequency Bands

Ofcom, the U.K. communications regulator, now is proposing to allow use of Long Term Evolution air interfaces in the existing 900 MHz, 1800 MHz and 2100 MHz bands to permit the deployment of 4G services.

The new LTE spectrum auctions will use the 800 MHz and 2.6 GHz bands.

The new rules would mean no restrictions on which air interfaces have to be used in each frequency band. That could become an important issue if one of the expected four leading winners of new LTE spectrum should be shut out, in part, or completely, in the current LTE spectrum auctions.

As always, spectrum auctions could have market-reshaping implications, either allowing new competitors to enter, or changing the strategic relationships between leading providers. But there is an important potential element: it is not clear there is enough spectrum for all four current leading mobile service providers to win new spectrum.

In fact, it seems likely that only three of four can win the auctions for coveted 800-MHz spectrum best suited for national networks.

That failure to win spectrum could put the loser at a severe disadvantage, compared to the other three leaders who win spectrum, it goes without saying.

Ofcom also will propose allowing an increase of 100 percent (3 decibels) in transmit power of radios in the 900 MHz frequency band for UMTS (3G) technology, as requested by Telefónica and Vodafone.

Such regulation by function has been a staple of licensing in many countries, including the United States, which explains why Clearwire had to ask for Federal Communications Commission permission to use its mobile satellite spectrum to support a terrestrial LTE mobile network.

The changes would allow all the major mobile operators to make business decisions about whether to transition their current networks to LTE based solely on business considerations.

The decision also means that, should one of the four leading U.K. service providers fail to win LTE spectrum in the current auctions, that firm would still be able to offer LTE using its existing spectrum.

While not as easy as deploying a network using brand-new spectrum, the change in Ofcom rules would protect any one of the four major firms from being shut out of the LTE business.

The new LTE spectrum auctions will use the 800 MHz and 2.6 GHz bands.

The new rules would mean no restrictions on which air interfaces have to be used in each frequency band. That could become an important issue if one of the expected four leading winners of new LTE spectrum should be shut out, in part, or completely, in the current LTE spectrum auctions.

As always, spectrum auctions could have market-reshaping implications, either allowing new competitors to enter, or changing the strategic relationships between leading providers. But there is an important potential element: it is not clear there is enough spectrum for all four current leading mobile service providers to win new spectrum.

In fact, it seems likely that only three of four can win the auctions for coveted 800-MHz spectrum best suited for national networks.

That failure to win spectrum could put the loser at a severe disadvantage, compared to the other three leaders who win spectrum, it goes without saying.

Ofcom also will propose allowing an increase of 100 percent (3 decibels) in transmit power of radios in the 900 MHz frequency band for UMTS (3G) technology, as requested by Telefónica and Vodafone.

Such regulation by function has been a staple of licensing in many countries, including the United States, which explains why Clearwire had to ask for Federal Communications Commission permission to use its mobile satellite spectrum to support a terrestrial LTE mobile network.

The changes would allow all the major mobile operators to make business decisions about whether to transition their current networks to LTE based solely on business considerations.

The decision also means that, should one of the four leading U.K. service providers fail to win LTE spectrum in the current auctions, that firm would still be able to offer LTE using its existing spectrum.

While not as easy as deploying a network using brand-new spectrum, the change in Ofcom rules would protect any one of the four major firms from being shut out of the LTE business.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

$50 Smart Phones for Emerging Markets in 2013, Gartner Predicts

"Semiconductor vendors that serve the mobile handset market must have a product strategy to address the low-cost smartphone platform, with $50 as a target in 2013," said Mark Hung, research director at Gartner.

That will be one of several developments that many who have worked in the communications business might find frankly surprising.

Most surprising of all, perhaps, is the "solving" of the problem of "giving telephone service to billions of people who never have made a phone call." These days, that is mostly a problem that is solved, or soon to be solved.

The next problem is related to another problem, namely the issue of how to get computing devices and networks to people who have never used a PC or the Internet. Most believe that mobile broadband is the answer to the access problem.

Smart phones are becoming one answer to the "affordable devices" issue. In fact, the arrival of the low-cost smart phone parallels the earlier effort to develop low cost PCs for users in emerging markets.

The new element is the availability of the tablet as a form factor likely to make a big difference in the "low cost PC" market, which has been the object of some attention over the last decade, under the one laptop per child or one tablet per child.

We probably will be surprised over the next decade or so by the extent to which broadband access and use of the Internet has blossomed, globally.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Virgin Media to Sell to Liberty Global?

Virgin Media is in takeover talks with U.S.-based conglomerate Liberty Global.

In some ways, assets changing hands in the communications and media business, while interesting for the firms and people involved, do not change the strategic backdrop of the affected markets. In other cases, there are strategic implications.

This deal would not appear to be so much strategic, as tactical. Liberty Media long has invested in European cable TV assets. So Virgin Media would represent a bigger profile in the U.K. market, not out of line with what Liberty Global has invested in, in the past.

The irresistible story line, though, is that a successful deal would pit Liberty Global's chairman, John Malone, head-to-head with Rupert Murdoch in the video entertainment business, as has been the case, from time to time, in the past.

In some ways, assets changing hands in the communications and media business, while interesting for the firms and people involved, do not change the strategic backdrop of the affected markets. In other cases, there are strategic implications.

This deal would not appear to be so much strategic, as tactical. Liberty Media long has invested in European cable TV assets. So Virgin Media would represent a bigger profile in the U.K. market, not out of line with what Liberty Global has invested in, in the past.

The irresistible story line, though, is that a successful deal would pit Liberty Global's chairman, John Malone, head-to-head with Rupert Murdoch in the video entertainment business, as has been the case, from time to time, in the past.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

New "National Wi-Fi" Story Doesn't Make Sense

Every now and then, we all run into a story that doesn't make sense. That seems to be the case with the notion that the Federal Communications Commission is about to enable the building of new forms of national Wi-Fi service. It is true that the FCC proposes to set aside some spectrum formerly used by TV broadcasters for unlicensed use.

Such uses have in the past created markets for garage door openers and what we now call "Wi-Fi." But so far as anybody really can tell, the FCC has not called for, or said it would directly or indirectly fund the construction of networks that use unlicensed spectrum.

It will simply make the frequencies available, and then private interests have to do the investing. Some refer to "white spaces" spectrum as "Super Wi-Fi." It is a catchy phrase. But nobody can yet tell whether that is the right analogy. Wi-Fi, after all, has been used as a local area communications protocol, not a "network access protocol."

And while it would be helpful, in an end user or Internet application provider sense, for new unlicensed spectrum to be made available, it would be more helpful for would-be network access providers to have additional spectrum resources.

Wi-Fi, in the sense of local distribution, is in the same category of things as the use of Ethernet cables or other methods of forwarding packets inside a home, office or other area. Between the local distribution network and the "Internet" is an access network of some kind. And the bigger business issue is access, not local distribution.

If "white spaces" could create a big new access channel, that would be big news. If used only for local distribution, indeed, as "Super Wi-Fi," that would probably not be so big a deal.

Recent stories about Google and France Telecom talking about "terminating access" are other cases in point, where a story just doesn't make sense.

In fact, that whole issue of Google paying access providers or content owners, both ways of redistributing profit in the Internet ecosystem, are a muddled matter. Given enough business or political pressure (such as threatened regulations), dominant and influential firms sometimes find they must make accommodations they would rather not.

So some would say Google now is "paying France Telecom" for access to Orange customers in Africa, something that would be quite a precedent for Google and any access provider. Others would say Google likewise is paying French content firms for the right to index their content. Google would say otherwise.

But the fact remains that firms sometimes have to bend. Google can rightly say it is not paying for access, only executing peering agreements or interconnection agreements. Google can rightly say it is helping French newspapers retool for a digital age. But France Telecom and French newspapers are going to be getting some revenue, for something, from Google, in ways that allow Google to say it is not paying for termination, or for the right to index content.

As with the case of "white spaces," the actual story is more nuanced than headlines would suggest.

Such uses have in the past created markets for garage door openers and what we now call "Wi-Fi." But so far as anybody really can tell, the FCC has not called for, or said it would directly or indirectly fund the construction of networks that use unlicensed spectrum.

It will simply make the frequencies available, and then private interests have to do the investing. Some refer to "white spaces" spectrum as "Super Wi-Fi." It is a catchy phrase. But nobody can yet tell whether that is the right analogy. Wi-Fi, after all, has been used as a local area communications protocol, not a "network access protocol."

And while it would be helpful, in an end user or Internet application provider sense, for new unlicensed spectrum to be made available, it would be more helpful for would-be network access providers to have additional spectrum resources.

Wi-Fi, in the sense of local distribution, is in the same category of things as the use of Ethernet cables or other methods of forwarding packets inside a home, office or other area. Between the local distribution network and the "Internet" is an access network of some kind. And the bigger business issue is access, not local distribution.

If "white spaces" could create a big new access channel, that would be big news. If used only for local distribution, indeed, as "Super Wi-Fi," that would probably not be so big a deal.

Recent stories about Google and France Telecom talking about "terminating access" are other cases in point, where a story just doesn't make sense.

In fact, that whole issue of Google paying access providers or content owners, both ways of redistributing profit in the Internet ecosystem, are a muddled matter. Given enough business or political pressure (such as threatened regulations), dominant and influential firms sometimes find they must make accommodations they would rather not.

So some would say Google now is "paying France Telecom" for access to Orange customers in Africa, something that would be quite a precedent for Google and any access provider. Others would say Google likewise is paying French content firms for the right to index their content. Google would say otherwise.

But the fact remains that firms sometimes have to bend. Google can rightly say it is not paying for access, only executing peering agreements or interconnection agreements. Google can rightly say it is helping French newspapers retool for a digital age. But France Telecom and French newspapers are going to be getting some revenue, for something, from Google, in ways that allow Google to say it is not paying for termination, or for the right to index content.

As with the case of "white spaces," the actual story is more nuanced than headlines would suggest.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Dell Encounters a Changing Era, As Did IBM, Microsoft: Will Apple be Next?

There's a good reason for eras of computing and the scary fact that no leader in one era has lead in the next era. Firms survive the shifts--IBM is the best example so far--but they do not lead in the same way they once did.

Historically, what it has taken to succeed in each era has required different architectures, has had firms engaging with different customers, or in different ways with customers, and has had different amounts of integration with other parts of life.

Some would say we have been though four eras, and are entering the fifth of five eras of computing, including mainframes, PCs and Web, while we now are entering the "Device" era, which will be followed by something Robert Grossman calls the "Data" era.

Others might say we have been through four eras, including mainframes, minicomputers, PCs and now are in an era where cloud or mobile might better characterize the new era.

The point is that, historically, these eras correspond to business leadership. It is therefore no knock on executive skill that firms such as Dell, HP, IBM and perhaps now even Apple have run into problems when eras change.

Most technology historians would agree there was a mainframe era of computing, followed by the mini-computer and then PC or client-server era. Most would agree that each era of computing has been lead by different companies.

IBM in the mainframe era; Digital Equipment Corp. in the mini-computer era and Microsoft and Intel in the PC (or Cisco in the client-server era, as one might also refer to the PC era) are examples. Apple has been among the brightest names in the current era, however one wishes to describe it. But judging by market valuation, Apple has hit a bit of an air pocket.

But there is no doubt there has been a change over the past decade or so. Where in the late 1990s one might have said EMC, Oracle, Cisco and Sun Microsystems were the four horsemen of the Internet, leading the business, nobody would say that in 2013.

These days, it is application firms such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, plus Apple, that fit into the typology.

There has been a trend towards computing pervasiveness, as each era has succeeded the earlier era. Computing used to be in a "glass room." Then it could be done in a closet. With PCs computing moved to the desktop. Now, computing is in a purse or pocket.

The role of software obviously has become more important over time. But, to this point, computing eras have never been defined by the key applications enabled. Perhaps we will one day see matters differently, but it would be a change to shift from "how" computing is done to "what computing does" to define the eras.

We all sense that a new era is coming, and that the Internet, mobile devices and applications will be more important. But there is not any agreement on whether we have "arrived" or are still only approaching the new era.

We certainly are leaving the PC era. That's why former Apple CEO Steve Jobs always insisted the iPad was not a PC. In fact, many would insist that it is the tablet's optimization for content consumption that makes it distinctive.

We can't yet say that the next era of computing is defined by mobile devices, tablets, the Internet or cloud computing or even the fact that leadership is shifting more in the direction of applications and activities than computing appliances. But all of that hints at the shape of what might be coming.

If history holds, someday even Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon will be seen as "former leaders." Despite the success those firms have enjoyed, there is still no precedent for a firm that leads in one era to lead in the next.

Michael Dell, about to execute a deal to take Dell private said the "rise of tablets had been unexpected."

"I didn't completely see that coming," he said.

Dell would be in good company. Bill Gates did not "get" the Internet, either.

Historically, what it has taken to succeed in each era has required different architectures, has had firms engaging with different customers, or in different ways with customers, and has had different amounts of integration with other parts of life.

Some would say we have been though four eras, and are entering the fifth of five eras of computing, including mainframes, PCs and Web, while we now are entering the "Device" era, which will be followed by something Robert Grossman calls the "Data" era.

Others might say we have been through four eras, including mainframes, minicomputers, PCs and now are in an era where cloud or mobile might better characterize the new era.

The point is that, historically, these eras correspond to business leadership. It is therefore no knock on executive skill that firms such as Dell, HP, IBM and perhaps now even Apple have run into problems when eras change.

Most technology historians would agree there was a mainframe era of computing, followed by the mini-computer and then PC or client-server era. Most would agree that each era of computing has been lead by different companies.

IBM in the mainframe era; Digital Equipment Corp. in the mini-computer era and Microsoft and Intel in the PC (or Cisco in the client-server era, as one might also refer to the PC era) are examples. Apple has been among the brightest names in the current era, however one wishes to describe it. But judging by market valuation, Apple has hit a bit of an air pocket.

But there is no doubt there has been a change over the past decade or so. Where in the late 1990s one might have said EMC, Oracle, Cisco and Sun Microsystems were the four horsemen of the Internet, leading the business, nobody would say that in 2013.

These days, it is application firms such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, plus Apple, that fit into the typology.

There has been a trend towards computing pervasiveness, as each era has succeeded the earlier era. Computing used to be in a "glass room." Then it could be done in a closet. With PCs computing moved to the desktop. Now, computing is in a purse or pocket.

The role of software obviously has become more important over time. But, to this point, computing eras have never been defined by the key applications enabled. Perhaps we will one day see matters differently, but it would be a change to shift from "how" computing is done to "what computing does" to define the eras.

We all sense that a new era is coming, and that the Internet, mobile devices and applications will be more important. But there is not any agreement on whether we have "arrived" or are still only approaching the new era.

We certainly are leaving the PC era. That's why former Apple CEO Steve Jobs always insisted the iPad was not a PC. In fact, many would insist that it is the tablet's optimization for content consumption that makes it distinctive.

We can't yet say that the next era of computing is defined by mobile devices, tablets, the Internet or cloud computing or even the fact that leadership is shifting more in the direction of applications and activities than computing appliances. But all of that hints at the shape of what might be coming.

If history holds, someday even Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon will be seen as "former leaders." Despite the success those firms have enjoyed, there is still no precedent for a firm that leads in one era to lead in the next.

And IBM has shown one way of surviving in an era a former leader cannot dominate. Dell wants to go the same route. But it might be fair to say that "surprise" is one common element when eras start to change.

Michael Dell, about to execute a deal to take Dell private said the "rise of tablets had been unexpected."

"I didn't completely see that coming," he said.

Dell would be in good company. Bill Gates did not "get" the Internet, either.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Useful Life of a GPU is Not So Clear

Perhaps depreciation is not typically a key business model issue, but that seems not to be the case for hyperscalers who have extended the ...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...