Will fifth generation networks be a “network of networks” or “heterogeneous network” rather than a single air interface on the model of 3G or 4G. That would be a big shift.

Will fifth generation networks be a “network of networks” or “heterogeneous network” rather than a single air interface on the model of 3G or 4G. That would be a big shift.

Traditionally, the difference between one generation of mobile networks and the next has been the air interface protocols. Now Ericsson thinks the key differentiator will be the ability to flexibly operate a virtual network that integrates many different air interfaces, protocols, frequencies and network types.

At least in part, Ericsson takes that view because of some differences between past next generation networks and future networks, namely the differences in speed and spectrum.

In the past, new mobile generations are typically assigned new frequency bands and wider spectral bandwidth per frequency channel (1G up to 30 kHz, 2G up to 200 kHz, 3G up to 5 MHz, and 4G up to 40 MHz).

The problem is that physical availability of spectrum usable for longer-range mobile apps is growing limited. And spectrum means bandwidth.

The problem is that physical availability of spectrum usable for longer-range mobile apps is growing limited. And spectrum means bandwidth.

At least so far, with the 4G standard calling for peak rates of about 1 Gbps, 5G will have a tough time offering “faster speed” as its distinguishing feature.

That means suppliers will be looking at battery life, coverage and throughput flexibility and the ability to match apps and device requirements in an affordable way.

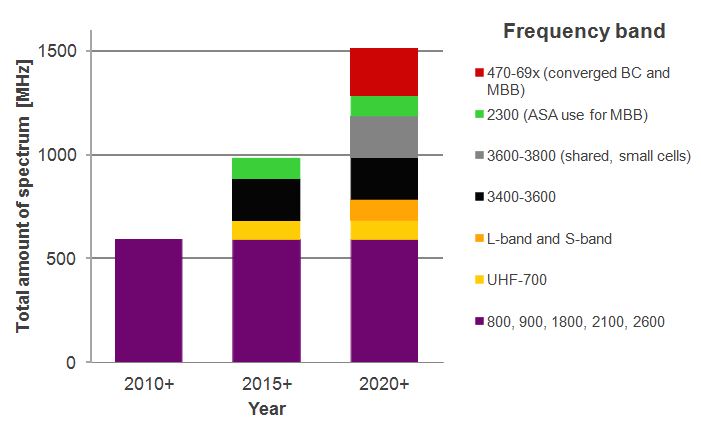

Some new spectrum will be made available. Spectrum in the 900 MHz, 1800 MHz, 2100 MHz and 2600 MHz bands will be used for new LTE networks and HSPA network capacity upgrades.

LTE deployments using 700 MHz and 800 MHz spectrum will be added as well.

Small cell deployments will play a vital role in high-capacity hotspots, and the spectrum for that could come from the 3500 MHz band, where there is as much as 400 MHz being used for fixed broadband wireless access and satellite services, Nokia Siemens Networks has said.

All of that points up the importance of spectrum sharing and other new methods of creating new bandwidth.

Unlicensed bands such as 5 GHz or 60 GHz will offer additional traffic offload options for best-effort traffic of less critical applications without quality requirements.

The result is that up to 1.5 GHz of spectrum can be made available within this decade, Nokia Siemens Networks believes. At least 1 GHz of that will be traditional exclusive spectrum, while new spectrum-sharing techniques can unlock more spectrum for mobile broadband.

So there are lots of good reasons why Ericsson thinks a 5G network will be quite different from earlier mobile network generations.

In addition to phones and PCs, game controllers, TVs and other devices people use, there will be millions of machine-to-machine devices and sensors also supported by the 5G network. And the point is that no single network is best for all apps and devices.

“The long-term outcome of this trend is what we refer to as 5G: the set of seamlessly integrated radio technologies” that collectively, integrated seamlessly, will represent a fifth generation of wireless networks, Ericsson argues in a white paper.

One huge assumption is that there will be a massive increase in the number of devices that must communicate. In the future, the roughly five billion human-centric connected devices are expected to be surpassed between 10-fold and 100-fold by communicating machines including surveillance cameras, smart-city, smart-home and smart-grid devices, and connected sensors.

So there is a massive scale issue: a transition from five billion devices to 50 billion or perhaps even 500 billion connected devices.

A thousand-fold increase in required bandwidth is the other huge assumption. Beyond 2020, wireless communication systems will have to support more than 1,000 times today’s traffic volume, Ericsson also argues.

But bandwidth requirements will vary. It is possible many M2M apps and devices will not require lots of bandwidth, while consumer apps might require hundreds of megabits and some shared-use locations will require gigabits.

Likewise, latency and reliability requirements will vary as well. So it will make sense to match requirements to network segments and capabilities to match use cases to cost and network requirement parameters.

So 5G might be radically different from earlier generations of mobile networks. First of all, should 5G develop as Ericsson foresees, it will be the first network that actually is a network of networks, not a single air interface. The complexity of such an undertaking also suggests 5G will not arrive in fully-formed fashion as soon as typically is the case for mobile networks, which tend to be replaced about every decade.