Speculation now is growing that Sprint and T-Mobile US will launch a risky merger effort in 2014, a move that has been debated and rumored about for a decade and a half.

It might be argued the bid is driven fundamentally by weakness, not strength, sometimes an unpromising portent of future success.

A bid would signal in part that favorable bidding rules in the upcoming 2015 auction of 600-MHz spectrum will not, in fact, help either company enough to survive over the long term.

Nor, Sprint seems to believe, can T-Mobile US sustain its blistering and so-far successful attack on industry packaging and pricing, with clear gains in subscribers, over the longer term. In fact, some already are predicting a slowdown in T-Mobile US subscriber gains.

Opponents of any such merger will undoubtedly point to the significant subscriber gains T-Mobile US has made since early 2013, a period where T-Mobile US reversed its customer losses and gained more than two million coveted postpaid customers in 2013.

But neither Sprint nor T-Mobile US executives seem presently to believe they can survive--and that is probably an accurate term--over the longer term unless they combine.

That is going to run head on into antitrust resistance, as Department of Justice officials already have signaled a preference for four leading mobile service providers. But that might ultimately be unsustainble, as French regulators now believe.

More importantly, there is some reason to believe a majority fof Federal Communications Commission commissioners might agree.

So Sprint and T-Mobile US think their gamble is worth an effort, now. The firms think the large mergers proposed by Comcast (to buy Time Warner Cable) and AT&T (to buy DirectTV) give a Sprint bid to buy T-Mobile US a bit of regulatory cover.

With other parts of the industry consolidating, Sprint will position its own deal as an effort to keep up. Without the merger of Sprint and T-Mobile US, the U.S. mobile market effectively will become a duopoly, advocates will argue.

But market structure issues are complicated. Dish Network still is planning its own entry into the market, as is Comcast, and both will do so using their own facilities and assets.

Even with any Sprint merger with T-Mobile US, there still could be four to five leading providers, eventually.

The bid is a clear gamble, as both antitrust authorities and members of the Federal Communications Commission have signaled discomfort with any such deal.

To be sure, large transformative acquisitions and mergers in the U.S. market always involve some elements of “gambling,” as antitrust authorities and the Federal Communications Commission, though generally supportive of past mergers in a prior couple of decades, have recently concluded that markets are about to become too concentrated, or already are too concentrated.

Despite an almost unbroken record of approval of transactions in the mobile, cable TV and telecom business for a couple of decades, just two major refusals can be noted: the rejection of AT&T’s effort to buy T-Mobile US in 2011, and the refusal to allow a merger between DirecTV and Dish Network in 2002.

Those two deals are notable because both would have reduced the number of suppliers in the mobile or satellite TV markets, as the Sprint deal would also accomplish.

And all three big deals--Comcast buying Time Warner Cable; AT&T buying DirecTV and Sprint buying T-Mobile US--would remove a supplier from the market.

To be sure, Comcast argues that there are no competitive complications, since Comcast does not presently compete with Time Warner Cable.

And there are strategic reasons why all the mergers might in some sense be viewed as defensive in nature. Virtually nobody disagrees with the premise that linear video subscription services, sooner or later, are going to be displaced by over the top alternatives.

Virtually nobody disagrees with the notion that voice and text messaging revenues are declining.

The number of fixed network voice lines purchased by customers will continue shrinking, while mobile operator text messaging and voice revenues likewise will be limited in the future.

Also, the number of potential leading providers in the mobile market is going to increase, no matter what happens with Sprint’s bid for T-Mobile US.

Dish Network is preparing to enter the U.S. mobile market, and Comcast is sure to follow.

Almost parenthetically, both Sprint and T-Mobile US seem to discount the strategic importance of bidding rules for the upcoming auction of 600-MHz spectrum that are designed to favor both Sprint and T-Mobile US.

Launching an acquisition in 2014 would effectively remove both Sprint and T-Mobile US from such favored bidding in the upcoming auction of 600-MHz spectrum.

That, in turn, is a signal, and not the only sign, that both firms think their future prospects--and even survival--hinge on gaining scale, soon, and not on additional low-frequency spectrum they might win in the 600-MHz auctions.

One might accurately characterize the motivations behind AT&T’s effort to buy T-Mobile USA, and Sprint’s effort to buy T-Mobile US, as fundamentally different.

AT&T, already a market leader, was making a bid to reinforce its leadership, at the same time closing off any effort by Sprint to gain scale by making its own bid for T-Mobile US.

Sprint and T-Mobile US are making a defensive move, hoping to gain enough scale to compete, and essentially acknowledging that neither firm, alone, is going to catch up to AT&T and Verizon, no matter how many brave words are uttered to that effect.

In fact, some believe the T-Mobile US assault, which has netted important subscriber gains, is unsustainable in the long run. Not only does T-Mobile US need to keep adding new customers at a very high rate, it eventually will have to turn from sacrificing profits, in order to gain customer share, to earning profits.

In other words, the problem with the “compete your way to growth” strategy--for either Sprint or T-Mobile US--is that it already might be doomed. Neither firm has the financial resources to sustain a long campaign to grab share by undermining the industry structure of prices and packaging.

Hence, the necessity of a gamble on a big merger. In fact, it is hard to say which firm loses more if an acquisition fails. Sprint probably would have to pay a breakup fee to T-Mobile US, so T-Mobile US gains, at the margin.

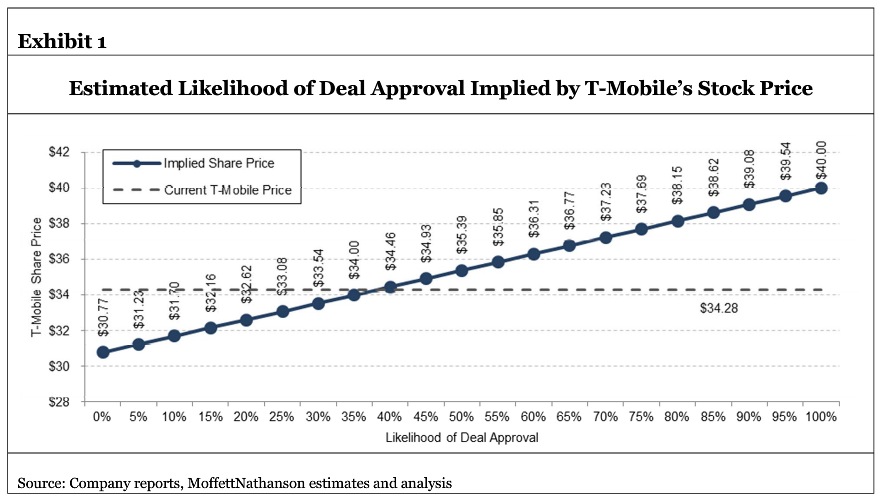

A vote at the FCC would be close. But Sprint and T-Mobile US both believe they have a shot at convincing a majority of commissioners to approve a deal, in part because as many as three of five commissioners might be receptive to the argument that robust competition is sustainable, long term, if there are three strong firms, nearly evenly matched, rather than two leaders and two smaller firms.

Also, the Comcast deal to buy Time Warner Cable and the AT&T bid for DirecTV might help Sprint make the case that on-going major market consolidation now forces Sprint and T-Mobile US to combine.

And even success is no panacea. Ask yourself: would you switch from AT&T or Verizon to Sprint, after a merger with T-Mobile US, if all offers from the combined company were about as they are now at T-Mobile US?

And do you think either AT&T or Verizon, or both, would not move to match those offers, to keep your account?

More significantly, would either AT&T or Verizon stand by while important postpaid multi-line accounts were taken?