Digital markets often are characterized by a winner take all market share, led by oligopolies. One might argue that always is the case, which is why antitrust law exists. Power laws and Pareto outcomes seem quite prevalent in nature and economics.

“Winner take all” outcomes arguably also happens for incomes of sports stars or other celebrities as well. The issue is why. Many cite the shift to intellectual capital as a reason for the rise of winner-take-all outcomes.

Other drivers are said to include economies of scale, scope and learning. Digital products and services have high fixed costs and low-to-zero marginal costs. That is scale. Scope is different. Such economies result when the production of one good makes production of another easier.

There also are economies of learning. You might call that the experience curve, or Henderson's Law. There is an inverse correlation between a product’s value added and the manufacturer’s experience in its production and marketing.

In other words, as a company’s understanding and knowledge increases, the cost per unit tends to decrease. That is going to apply for artificial intelligence as it gains knowledge of particular tasks.

Network effects can exist, where each additional node on a network increases the value of the whole network. One can consider fads and fashion an example of network effect.

Platform business models also seem to encourage oligopolies. Platform businesses create value and earn revenue by matching complementary sets of people. Platforms make their money by extracting a transaction fee of some sort for connecting buyers and sellers, once they reach critical mass.

Platform business models also are“multi-sided” and facilitate transactions between many types of users. That is why the notion of “ecosystems” is so prevalent. Also, a multi-sided market allows users to switch roles. A renter can become a housing supplier. A rider can become a ridesharing driver. A message sender is normally also a message recipient. Content producers are content consumers.

Some might credit sophisticated analytics, allowing mining of huge data sets, as also contributing to winner-take-all outcomes. As some colloquially note, “he wins who has the most data.”

Brand value also will tend to reinforce winner-take-all outcomes. Sometimes that happens because brands create ecosystems of goods, services and suppliers that “lock customers into a platform” by creating higher switching costs.

Ironically, lower barriers to scale and competition might be among the reasons the “rule of three” (for example) seems so prevalent in digital markets. But some would note that most markets are oligopolies, digital or not.

Others might mention the prevalence of leverage, luck or feedback loops as causes of the outcomes. Whatever the reason, relative performance, rather than absolute performance, is key.

“Top performers might be only slightly more skilled than the people one level below them, yet they receive an exponential payoff,” says Farnam Street. “A small difference in relative performance—an athlete who can run 100 meters a few microseconds faster, a leader who can make better decisions, an opera singer who can go a little higher—can mean the difference between a lucrative career and relative obscurity.”

Were value deemed absolute, then a product or service with 90 percent of the performance of the “best” option would sell for 90 percent of the price of the “best” option.

But what we often see in digital markets is that the “best” product gets 50 percent to 80 percent market share. The 10th-best product, with 90 percent of the best product’s utility, gets almost no share.

That “winner take all” pattern arguably is true of digital goods in part because marginal costs are close to zero and because network effects often are generated. The former means the cost of supplying very-high demand is not onerous. The latter means utility grows exponentially with scale.

Connectivity services tend not to exhibit that pattern as well, sometimes because high capital investment requirements discourage competitors.

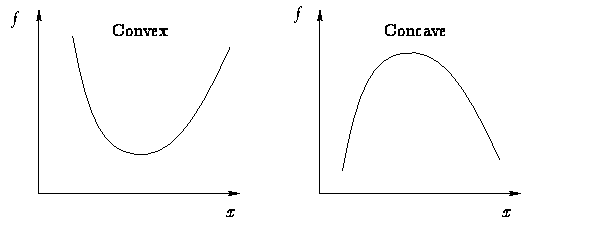

Back in 1981 economist Sherwin Rosen wrote about the phenomenon. Convexity is the principle that small differences in talent become magnified in larger earnings differences.

source: Medium

source: Medium

Imperfect substitution is another concept that explains why “winner take all” markets develop. That can be driven by the value of an ecosystem of goods and services, brand preferences, switching costs or any other combination of values that create product differentiation.

“Winner take all” might always have been an issue, but it is magnified in an era where digital economics operate.