The Carphone Warehouse Group (U.K. market), which might formerly have been thought of as an electronics retailer, now points out how much communications service distribution channels can change.

Carphone Warehouse now has 2.6 million Digital Subscriber Line customers. It is by no means certain that mass market retailers in other markets will do as well, but both Best Buy, Office Depot and Circuit City, for example, are distribution channels in the U.S. market, with differing degrees of active involvement in the integration and broadband access businesses. In the U.S. market, Best Buy has taken the boldest steps by buying Speakeasy, a national provider of DSL connections.

Friday, January 18, 2008

Carphone Warehouse Now Major DSL Channel

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Brazil, Russia, India and China Driving Growth

In 2007, Hewlett Packard earned 67 percent of its total revenue outside the U.S. market. In the fourth quarter along, Asia-Pacific grew by 20 percent, Europe, Middle East and Africa by 19 percent and the Americas region was up by 10 percent. The Brazil, Russia, India and China group grew 37 percent year over year in the fourth quarter. Growth rates of that sort are one reason new submarine cables are being laid between North America and the Far East, and being planned or talked about between Europe and India. Add mobile phones to the growth of PC and associated electronics and it is clear Asia, the Middle East and Africa is where the growth is, at least in terms of mobile and other sorts of communications.

Of course, there are other reasons for laying additional cables across the Pacific. Earthquakes are capable of taking out multiple cables and routes in an instant, so carriers logically want more redundancy on trans-Pacific routes than has been the case up to this point.

Labels:

China Mobile,

global revenue,

global telecom,

India

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Ads: $5 Million a Day Shifts to Online

One way to look at current trends in where advertising is being bought is to note that "ad dollars are leaving the cable, broadcast TV and the newspaper business at a rate of roughly $5 million per day, says Paul Woidke, Comcast Spotlight VP.

Labels:

online advertising

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Time of Day Pricing

As exemplified by this chart showing how utilities price usage by time to day to discourage use during periods of peak load, one theoretically could price broadband access, voice or virtually any other communications good based on time of day or day of week. Long distance pricing used to do so, in fact.

As exemplified by this chart showing how utilities price usage by time to day to discourage use during periods of peak load, one theoretically could price broadband access, voice or virtually any other communications good based on time of day or day of week. Long distance pricing used to do so, in fact.Of course, what we now know is that users vastly prefer flat rates, often because it is a way to avoid steep "overage" charges, and even when the actual price for usage is much higher than one might think. Based on what one did in a single billing period, for example, average prices for wireless calling might range from two cents a minute to eight cents or more. When one is on vacation, per-minute pricing might be as high as 20 to 25 cents a minute for the actual minutes used.

Most U.S. consumers probably don't worry about "per minute" pricing for domestic calling. They pay a flat rate for a certain number of minutes in a bucket, and that's about as far as one normally thinks about the matter.

Not so long ago, though, wireless calling and wired network calling routinely used time of day pricing. In principle, broadband access could be priced the same way. It is doubtful the potential benefits are worth the effort. Customers clearly prefer buckets and flat rate pricing. Also, there are costs associated with tracking usage so closely, so in most cases it might not be worth the effort.

The other issue is that pricing by the value of an application makes more sense than tracking raw bandwidth usage. The value of a text message or voice bit is quite high on a price-per-bit basis. On the other hand, the value of high-quality video video or audio bits is not determined so much by price-per-bit as by quality of the streams.

One movie might be "worth" the $3 or $4 a user pays for the stream. But the value will be determined by the quality of the delivered images. Two hours of continuous talking might be valued just as highly, even if the perceived price is $2.40 (two cents a minute for 120 minutes).

Time of day pricing also arguably makes less sense for broadband because network load tends to balance out, if one includes business broadband and consumer broadband load. Business load is high from 8 a.m. until perhaps 4 p.m. while consumer usage peaks in the evening. Average load therefore tends to balance on any given network from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. local time, though usage obviously is lighter from midnight to 6 a.m.

Labels:

broadband,

broadband access,

cable modem,

DSL

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Usage-Based Pricing Not Unusual

At some point, as more Internet service providers begin to adopt "buckets" of use as the dominant subscription model, there will be outcries about whether this is fair, since most users in the U.S. market have come to expect flat fee pricing for "unlimited" use.

That has not been the dominant model in Europe, for example, and though there might be some incremental impact in usage patterns, I don't think anybody would argue that metered usage is terribly and inherently unfriendly.

It also is highly unlikely to the point of implausibility that ISPs in the U.S. market will move to a strict metered usage regime. The reason is simply that the objective--matching consumption to the cost of providing access--can be addressed more simply and palatably by using the "bucket" model, much as mobile calling or texting plans can be purchased based on expected usage.

In that regard, it might be helpful to recall that consumer pricing has used any number of models. Pay-as-you-go had been the dominant packaging and pricing model for all long distance plans, mobile and fixed, until at&t introduced "Digital One Rate." Local calling, on the other hand, has used a "fixed fee, all you can eat" model.

Cable TV has used a mixed model: essentially "flat fee, all you can eat" for ad-supported video and movie channels, but usage-based pricing for on-demand pricing.

The model used for Internet access started at the other end of the continuum: unlimited use (subject to some acceptable use policies) for a flat fee. Only recently have some voice providers moved to that model.

Of late, though, there has been a bigger move to "buckets" that match usage to price. There's no particular reason to believe a move in that direction will affect the vast majority of users. Most customers have usage patterns that fall within a reasonable zone, and won't, in practice, notice anything different even if usage-based pricing becomes more prevalent.

Providers obviously will want to minimize disruption, and there's no question but that lower prices have driven high demand. Nobody will want to jeopardize their market share by raising prices for most customers other than the small percentage who consume a disproportionate share of bandwidth.

Over time, more attention will have to be paid to the relationship between retail pricing and usage as video starts to change usage patterns, though.

Labels:

broadband access,

cable modem,

DSL,

FiOS

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Apple, Netflix ramp up Online Video Efforts

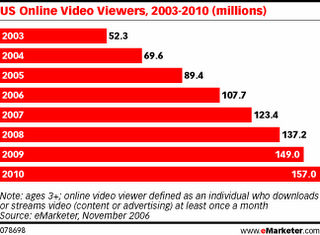

There are many reasons lots of people ought to be paying attention to streaming and downloaded video. Lots of people work for companies making a living delivering video products and everybody watches video in its various forms. Lots of companies are making expensive bets about what people want to watch, how and where they want to watch, what features are required and how much they will watch. The two mid-January developments in the area of particular note are the Netflix "unlimited online viewing" offer and Apple's launch of a video download service.

Up to this point Netflix has allowed its subscribers to watch online movies on a limited basis, corresponding to their monthly plans. Basically, hours of online viewing roughly correlated to the monthly subscription price. The big change is that Netflix now allows users on unlimited rental plans starting at $8.99 a month to stream as many movies and TV episodes as they want on their PCs, choosing from a library of over 6,000 familiar movies and TV episodes.

Now, subscribers on unlimited plans can stream as many movies and TV episodes as they want from the smaller instant watching library, unconstrained by any hourly limits. The move widely is viewed as a preemptive response to Apple's launching of its own video download service, using a rental model rather than "download to own" approach. Up to this point Apple has seen modest success with an approach based on Apple TV hardware and content from two studios, Disney and Paramount.

All major Hollywood studios have agreed to make their content available as part of the new Apple service. They include Paramount, Universal, Walt Disney, Warner Bros, Sony Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Lionsgate, New Line and News Corp's Fox.

Using Apple's iTunes online store, US consumers will be able to hire new-release movies at $3.99 for 30 days. Older titles are priced at $2.99 for the same duration.

These movies can be viewed on iPhones, iPods and television. One can debate the impact of Apple's more-aggressive move into online downloads and streaming. In fact, one can argue that the streaming business is a different segment from the "download to own" market or the "rent by downloading" segment.

One also can debate who wins and loses in the video rental business: Netflix, Blockbuster, Amazon.com, Joost, iTunes or others. Even the impact on Netflix is debatable. If consumer use of the streaming feature increases, Netflix will pay more money in licensing fees to the studios who own the content. It also will incur more bandwidth charges. On the other hand, Netflix might spend less money on postal charges, shipping and handling of physical DVDs.

Probably more important is the strategic impact: Netflix's ability to retain existing market share as new competitors enter the market.

The other issue is which market is affected. To some extent the "view on PC" segment is where Apple, Netflix and others compete head to head. There are other segments, such as the "watch on my iPod" market, where Netflix and others delivering to the PC do not play.

Also, one might debate whether a subscription service is different from a pay-per-view model. Heavier users arguably will prefer a subscription model. Lighter users might well prefer the "pay as you go" model. Also, there is little question but that mobile, iPod, PC and TV viewing segments will emerge as full-fledged markets at some point, irrespective of the payment model.

Business motivations also are different. Apple sells content at prices as low as possible so it can create a market for its devices. Its market is rNetazors (devices) not razor blades (recurring revenue). Netflix has the opposite business model: it only cares about devices as platforms to sell content on a recurring basis.

To some extent, then, Netflix and iTunes ultimately compete with telco, wireless and cable on-demand programming offerings, in addition to competing with each other to some extent. Netflix and iTunes now are in the video on demand business, not the "DVD rental" business.

Telcos and cable companies investing heavily in broadband access networks play in the linear TV space as well as the on-demand video space. They compete directly with each other and satellite providers. But over time each of the three main linear programming providers also competes in the on-demand entertainment market, especially as such viewing can be supported on TV screens at some point.

Labels:

Blockbuster,

iTunes,

Joost,

Netflix,

online movies,

VOD

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Test of Tiered Pricing for Broadband Access

Time Warner Cable is testing usage-based broadband access pricing, according to Broadbandreports.com. The move is hardly surprising. Most Internet service providers report that a fraction of all users, about five percent or so, use over half of all access bandwidth.

The Time Warner test presumably aims to discover how such usage can be monitored by end users themselves, how scalable the process might be, and possibly whether such heavy users will upgrade to higher-usage plans or flee to another provider.

Over time, it seems inevitable that heavier users will find themselves facing universal caps on their usage and the ability to buy plans that support their higher usage levels.

Broadandreports.com says the test will involve new customers in the Beaumont market, not existing customers. Those users will be placed on metered billing plans where overage charges will apply, and provided a web site where they can track their usage and upgrade, if required.

In principle, the approach is akin to how mobile pricing plans now are structured, where users can choose higher usage or lower usage plans for voice and text usage.

One way or the other, as video becomes a bigger part of overall broadband usage, it is inevitable that usage-based plans supplant current "all you can eat" plans. Video is the reason.

Video consumes vastly more bandwidth than Web surfing, email or voice, requiring across the board capacity increases in the network backbone and access networks. That obviously costs money, and those costs will have to be recovered.

Usage-based pricing is coming because it has to.

Labels:

broadband access,

broadband cost,

Time Warner Cable

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Don't Expect Measurable AI Productivity Boost in the Short Term

Many have high expectations for the impact artificial intelligence could have on productivity. Longer term, that seems likely, even if it mi...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

Who gets to use spectrum, and concerns about interference from other users, now appears to be an issue for Google’s Project Loon in India. ...