Aside from the business advantages opponents in the network neutrality debates may perceive, there also are historic reasons why telecom interests want the ability to provide quality of service features.

Aside from industry culture, founded and built on the notion of “five nines” availability (uptime of 99.999 percent), QoS is, by definition, part of the global industry’s vision of the “next generation network.”

According to the International Telecommunications Union, “a Next Generation Network (NGN) is a packet-based network able to provide services including Telecommunication Services and able to make use of multiple broadband, QoS-enabled transport technologies and in which service-related functions are independent from underlying transport-related technologies.”

Note the key phrase “QoS-enabled.” The ability to provide guaranteed performance is, and has been, a key requirement for telco networks, including the present generation of networks.

You might say that telcos still have the ability to apply QoS to their own managed service (voice, messaging, video entertainment). That was true in an analog environment. It is not so clear that remains true in an IP environment, however. \

Service provider branded voice might feature QoS (Voice over LTE and non-IP digital voice, for example). But any use of voice over IP or voice over Wi-Fi is not going to have such quality protections.

And as telcos move to supply entertainment video on an on-demand, internet-delivered basis, no QoS is allowable when strong versions of network neutrality prevail. That primarily refers to rules that bar any consumer service provider from applying QoS mechanisms, forcing all packets to be delivered “best effort.”

Again, the point is simply that the global vision for an NGN has been a network that is packet based, QoS enabled and which separates transport from apps.

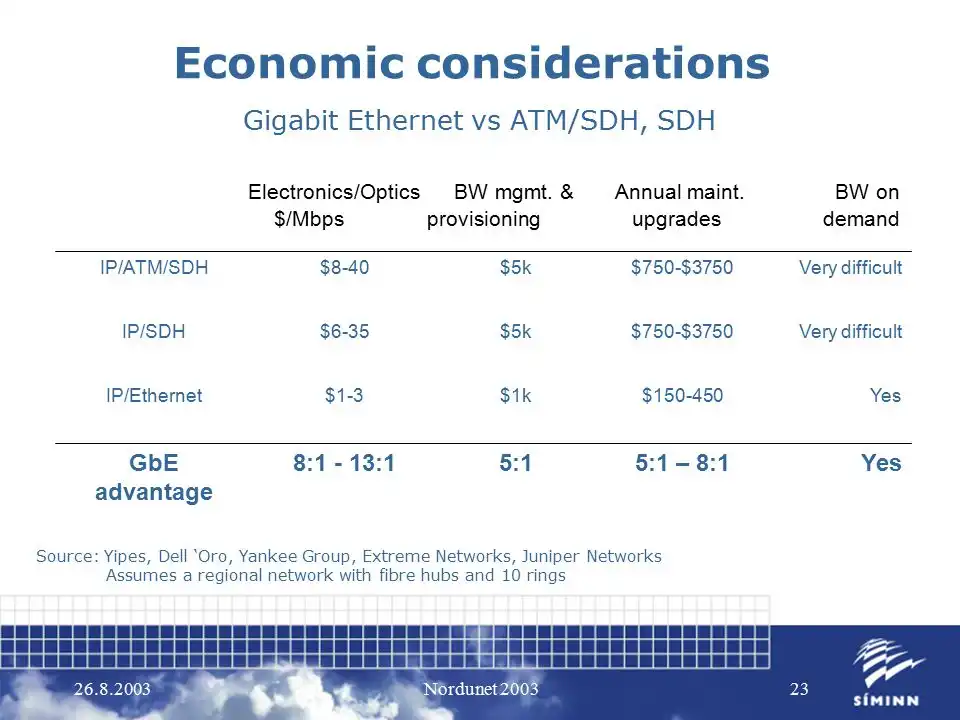

Without QoS, telecom interests are always going to believe the vision is incomplete. Of course, for the better part of a decade, strategists debated the merits of ATM and IP as the foundation of the coming future network. ATM, by definition, it was argued, supported QoS, while IP was, also by definition, “best effort.”

Eventually, business model issues won the day: ATM interfaces were simply too expensive, and too complex, compared to the cost and simplicity of an IP interface. But proponents tried everything, including encapsulating IP over an ATM infrastructure, to try and keep ATM alive.