Fixed wireless based on 5G might have very different economics than older fixed wireless networks, if firms such as Verizon and T-Mobile actually can supply fixed access using the same radio network as they are building to support mobility services.

That is the same logic behind “multi-purpose” rather than “single-purpose” networks: sell multiple products using one network. Some early modeling suggested skepticism about the business model, but there was similar skepticism about the cost of 5G networks in general, which has proven incorrect, as 5G network capex is far lower than many feared.

Basically, if the capital investment to support mobile 5G also can be used to support fixed access, using customer premises gear only, and with no modifications to the mobile infrastructure, then the incremental cost of fixed access is “success-based.”

We have seen this before. The economics are similar to those of optical fiber business networks in business areas, where each additional customer is served by construction of a short lateral. Most of the capex is invested in the core access network, with only modest additional costs to connect new customers.

source: Verizon

In past years, that would have seemed quite impossible. Mobile networks could not support fixed network bandwidths at comparable retail prices. In principle, that is possible when 5G uses millimeter wave, shared or unlicensed spectrum.

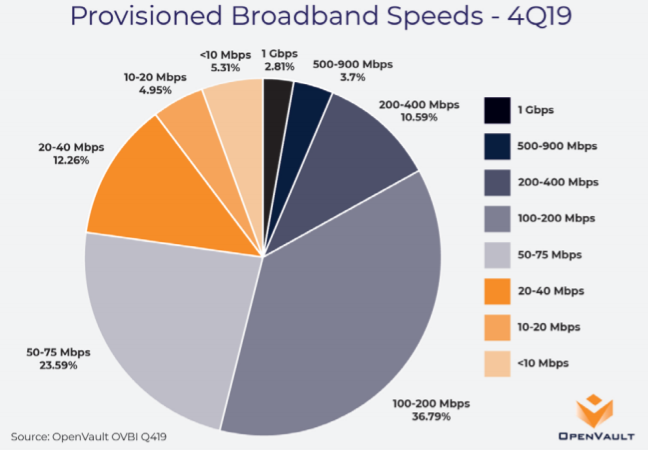

Nor must 5G fixed wireless necessarily fully replicate fixed network speeds, as most customers do not buy the “fastest” tier of service.

By the end of 2019, for example, just three percent of customers tracked by OpenVault purchased gigabit per second internet access. Nearly four percent bought service at between 500 Mbps and 900 Mbps. Some 11 percent purchased service running between 200 Mbps and 400 Mbps.

About 37 percent bought service operating between 100 Mbps and 200 Mbps, while 24 percent had services running between 50 Mbps and 75 Mbps.

“Most” consumers buy plans with features, compared to price, broadly “in the middle” of available plans. “Most” buy neither the most-expensive nor the most-affordable plans; neither the “highest usage” nor the “sharply limited” usage plans.

source: OpenVault

source: OpenVault

The point is that a 5G fixed wireless service can be pitched to “most” customers without having to supply the fastest expected fixed network speed.

Looking at slightly-older data by OpenVault, in the United States and Western Europe, about 1.85 percent of subscribers tracked by OpenVault buy gigabit-speed service.

Some 3.5 percent buy services running between 300 Mbps and 500 Mbps, while seven percent buy service at speeds between 200 Mbps to 300 Mbps.

About 65 percent buy services running between 50 Mbps and 150 Mbps, Openvault data shows.

Most people are not power users, either. Perhaps 60 percent of internet users consume less than 250 gigabytes a month. Perhaps 34 percent consumer more than 250 GB but less than 1,000 GB per month. Perhaps four percent of users consume more than 1,000 GB per month.

source: OpenVault

The market for 5G fixed wireless might be more attractive than many suppose, even if it does not routinely offer gigabit speeds.