Facing important decisions about potential consolidation in both video entertainment and mobile industry segments, Federal Communications Commission decisions, along with Department of Justice antitrust reviews, could trigger other cross-industry consolidation as well.

The immediate issues include the Comcast acquisition of Time Warner Cable, the possible, though unlikely Sprint acquisition of T-Mobile US and a potential merger between DirecTV and Dish Network.

Also in the background are upcoming auctions of former TV broadcast spectrum that likely will limit potential gains by AT&T and Verizon, while favoring Sprint and T-Mobile US.

All those intramodal changes could also trigger intermodal activity, though. Dish Network has been amassing spectrum suitable for building a mobile business based on fourth generation Long Term Evolution.

Dish faces an FCC deadline for beginning and finishing construction of that network, in order to keep its licenses. So there has been logical speculation about a deal with Sprint, for example, to expedite the actual network activation process.

But there are other possibilities as well. Both AT&T and Verizon face some limits on how big their existing linear video services business can grow. And some would question the long term value as well.

Dish Network CEO Charlie Ergen sees a dwindling future for satellite-based video service, and also for fixed network delivered linear video entertainment, as demand shifts to over the top and on-demand delivery.

“In my opinion, the video business for a monthly subscription of $80 to $100 a month is a mature business,” Ergen has said. “We’re losing a whole generation of individuals who aren’t going to buy into that model because they only want one particular show or they want to watch the show wherever they can or they want to watch it on their schedule and so that generation is not signing up to satellite or cable or phone video today.”

“At some point in time, the video business, as we know it today, will change dramatically enough that the current business will go from a mature business to a declining business,” Ergen has candidly said. “Hopefully, we’ll make up for that and in an over-the-top business or a wireless business or other businesses that make sense.”

That, many would argue, explains Dish Network’s effort to buy Clearwire and Sprint, purchases of satellite spectrum that can be repurposed to support terrestrial LTE and H block spectrum purchases.

Though initially some speculated that Ergen was buying all that spectrum, and talking about mobile networks, only to entice a buyer for all of Dish Network, Ergen now arguably is quite serious about shifting his business model.

Though initially some speculated that Ergen was buying all that spectrum, and talking about mobile networks, only to entice a buyer for all of Dish Network, Ergen now arguably is quite serious about shifting his business model.

For AT&T or Verizon, a shrinking fixed network linear video business could make a mobile-centric, over the top and on-demand video service much more attractive, positioning either carrier in a growing revenue segment that would become the successor to the linear video business.

Such a business also would be national in scope, where each carrier now has a limited geographic footprint. Also, should Google Fiber continue to scale its business, AT&T or Verizon would gain some revenue to offset possible losses in the fixed network and video services business.

The Federal Communications Commission seems to be interested in crafting auction rules that would ensure that T-Mobile US and Sprint get a reasonable share of the new spectrum.

This is important and valuable to both carriers as the new frequencies will propagate farther than the higher-frequency holdings that anchor both carriers’ present services. Greater propagation means less capital cost for the transmitting network.

But those bidding restrictions also would limit the additional spectrum AT&T or Verizon could acquire.

To be sure, Verizon has said it has no need for more spectrum for additional spectrum. But Verizon already has invested in assets that would allow it to launch a nationwide, mobile-delivered over the top video service. And that would take lots more bandwidth than Verizon presently controls.

Verizon’s public statements notwithstanding, it almost certainly will be needing more spectrum, not so much for its “mobile communications” services, but for potentially key new mobile video entertainment services.

And that is where Dish Network could come into play. Dish owns enough spectrum to be attractive if Verizon or AT&T are serious about a mobile-delivered, over the top and on-demand video entertainment service.

Keep in mind that Verizon’s FiOS footprint is relatively small, compared that of Comcast and the satellite networks, for example.

Keep in mind that Verizon’s FiOS footprint is relatively small, compared that of Comcast and the satellite networks, for example.

One might argue that will happen. The traditional argument--for at least a decade--is that neither AT&T nor Verizon can grow the video portion of their triple-play services much more than incrementally, without acquiring more video share now held by the satellite providers.

No matter how effective the telcos are at marketing video services, they are hampered for a couple of reasons.

The cost of upgrading their fixed networks to handle video is a task now made tougher because the financial return from investing in mobile assets now competes for investment funds, is one limitation.

AT&T and Verizon have very good reasons for caution about capital investment in their fixed networks, even if high speed access and video entertainment services have emerged as strategic applications for fixed networks.

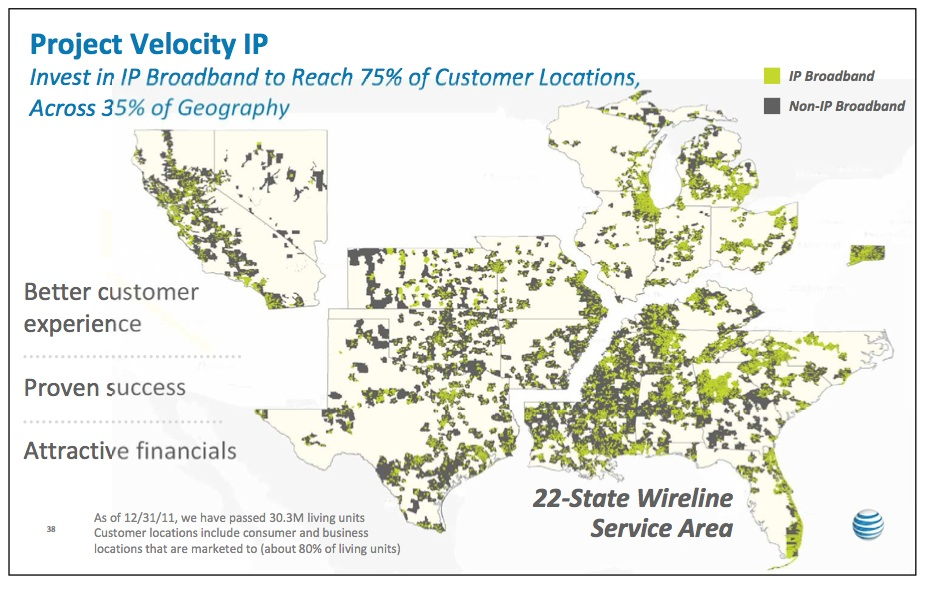

The other problem is that both firms are barred from significant growth by acquisition, simply because of their large share of the telco fixed network business. AT&T’s fixed network might pass about 30 million of 115 million or so U.S. homes, and not all those locations are video-capable.

Verizon passes about 27 million homes. And despite new AT&T plans to vastly accelerate upgrading its networks, perhaps half of all lines operated by AT&T and Verizon fixed networks are not yet upgraded to enable video services.

The point is that AT&T and Verizon will be limited in the number of video subscribers they can attract, simply because their footprints are relatively limited, both geographically and in terms of the cost of upgrading rapidly.

Verizon’s video entertainment customer base, for example, is about five million households. DirecTV has about 20 million customers while Comcast, with Time Warner Cable, would have more than 30 million customers. Dish Network has about 14 million customers.

No matter how effective Verizon is at winning video market share where it has fixed network FiOS assets, the fact is that Verizon’s network footprint is too small, relative to the satellite networks, Comcast or AT&T, to grow its business too much further.

AT&T has about 5.5 million video customers as well. One might argue that the only way either AT&T or Verizon gets significantly more video share is by buying one of the satellite providers.

To the extent that national footprint is helpful, as it has become in the mobile business, national scale arguably would be beneficial in the video business, as both DirecTV and Dish Network are able to take advantage of, in terms of marketing and to some extent in terms of appeal to advertisers.

Not only does Ergen expect demand for linear video to decline, geostationary satellite networks are ill-suited for interactive services.

But to the extent that linear video remains a key revenue driver, acquisition of Dish Network and DirecTV subscriber bases are one of the most-logical ways for AT&T and Verizon to gain scale and revenue volume in the linear video business.

Dish also offers Verizon a service organization outside of FiOS areas that could help Verizon deploy additional mobile broadband capacity and support an over the top mobile video service.

And either AT&T or Verizon would have more headroom to acquire additional spectrum from such a secondary transaction if the FCC revises the “spectrum screen” it uses to ensure diversity of spectrum ownership.

Essentially, the FCC limits ownership by any provider to no more than about 33 percent of available spectrum. In recent days, the Commission has not included 2.5-GHz Sprint holdings in the base, for such purposes.

Many believe that will change, automatically giving AT&T and Verizon more leeway to acquire spectrum in secondary markets (by buying firms with rights to spectrum). Dish Network is the firm with the greatest amount of spectrum to be acquired in that manner.

So watch for big intermodal changes in the U.S. mobile and video services business.