Orange CEO Stephane Richard says Google now pays an unspecified fee to Orange for essentially terminating Google traffic on Orange end points. That might be true, but might not mean much of anything.

The agreement appears to be a voluntary business-to-business agreement between Google and Orange that should be not be properly characterized as a case of Google "paying Orange for access."

It appears to be more like a standard IP transit arrangement between two networks with unequal traffic volume.

Separately, European content firms have been arguing for mandatory payment of fees of some sort for use of their content in Google's search results displays.

Both of those issues--new Internet forms of intercarrier compensation and participation in Google's advertising revenues--illustrate the difficulties regulators will face in crafting appropriate regulatory frameworks for IP-delivered content and usage of IP network resources.

Traditional regulatory models do not work so well in an IP context. Application or media providers do not have traditional intercarrier compensation obligations. But there is little question today's new IP network traffic generators--video, media and content apps--impose "use of network" cost issues very similar to traditional intercarrier termination issues.

Nor does the traditional media model work so well. Traditionally, media have used their owned networks to deliver their content. TV broadcasters, radio broadcasters, newspapers and magazines provide the key examples in a classic sense.

Cable networks long ago became a new model, though. To be sure, local TV and radio broadcasters have commercial relationships with their content suppliers. But cable operators have taken the model much further, essentially signing up whole programming networks and then packaging those networks for delivery to cable customers.

There is no intercarrier compensation analogy there, since cable operators own their own networks. The problem with IP content is precisely that the ownership of the networks and ownership of content are separated, by design.

Current regulatory frameworks were not designed for such business arrangements. For media and cable TV style business models, there is a well-understood framework for sharing revenue created by the services, but those arrangements do not require intercarrier compensation mechanisms.

The problem is that all networks are becoming IP networks, which, by design, separate the network access from the content people use on those networks. And there is, by design, no reason for actual bilateral business relationships between the providers of network access and the providers of content.

It's a growing and important issue, and app providers will have to make business decisions the way communications carriers sometimes must: make voluntary business arrangements that solve a problem or wait for regulators and legislators to "do it for them."

The reported deal between Orange and Google is something more akin to a cable TV network carriage agreement than anything else. Some won't like that.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Orange Says Google Pays Orange for Carriage

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

AT&T Warns of Lower Long-Term Rates of Return on Investments

AT&T has lowered its expected long-term rate of return for pension obligations due to the continued uncertainty in the securities markets and the U.S. economy in 2013. AT&T will book at $10 billion charge in the fourth quarter to compensate.

Verizon is taking a $7 billion charge in the fourth quarter, to cover pension obligations of its own.

AT&T said the changes will not affect It said the pension loss will not affect its operating results or margins.

Still, the shortfall in pension obligations, which largely reflect assumptions about interest rates, will strike some as unsettling.

Verizon is taking a $7 billion charge in the fourth quarter, to cover pension obligations of its own.

AT&T said the changes will not affect It said the pension loss will not affect its operating results or margins.

Still, the shortfall in pension obligations, which largely reflect assumptions about interest rates, will strike some as unsettling.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

What Makes Messaging Different?

Line, the Asia-based instant messaging app, says it has reached 100 million downloads in 18 months. That sort of raises the issue of how over the top instant messaging apps are different from text messaging.

In many cases, instant messaging is a relatively straight forward substitute for text messaging, the value being that users do not incur incremental costs. WhatsApp and Kik might be examples of that use case.

But Line seems more akin to chat (broadcast messaging), than text messaging (person to person communications). In other ways, Line seems like a gaming portal, and less like a simple substitute for text messaging.

But Line also is a bit like a social network as well.

Line also has become an over-the-top voice calling app. The point is that it isn't so easy these days to describe how "instant messaging" is different from "text messaging."

Text messaging and IM are in many ways substitute products. But sometimes even that distinction is inadequate. Messaging seems to be evolving.

In many cases, instant messaging is a relatively straight forward substitute for text messaging, the value being that users do not incur incremental costs. WhatsApp and Kik might be examples of that use case.

But Line seems more akin to chat (broadcast messaging), than text messaging (person to person communications). In other ways, Line seems like a gaming portal, and less like a simple substitute for text messaging.

But Line also is a bit like a social network as well.

Line also has become an over-the-top voice calling app. The point is that it isn't so easy these days to describe how "instant messaging" is different from "text messaging."

Text messaging and IM are in many ways substitute products. But sometimes even that distinction is inadequate. Messaging seems to be evolving.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Subscriber Growth Dwindles in U.S. Market: What Will Carriers Do?

There are basically two major ways mobile service providers or fixed network service providers can grow revenues: they can add more units (subscribers) or grow revenue per unit (average revenue per user).

And it is starting to look as though even mobile services, which have been the growth driver for the U.S. telecommunications industry, is facing a new era, when subscriber growth in the internal market can be propped up, near term, mostly by acquiring other firms. In other words, the internal U.S. market is approaching a zero-sum game, where one carrier can gain only by taking share from another supplier.

That is one primary reason why U.S. suppliers are so interested in machine-to-machine services, as that could add unit growth from telemetry services sold to other enterprises, rather than “humans.”

Average revenue per unit is a contest at the moment. Service providers face potential erosion of voice and text messaging revenues, though that has for the most part been a muted trend in the U.S. market, as real as it has become in some other markets, particularly in Europe.

But average revenue per unit is now driven by mobile broadband, which can grow for some time, though not indefinitely. Right now, it is unit growth that is the biggest issue.

Retail net additions (postpay and prepaid net additions) for the three largest U.S. wireless service providers declined 23 percent on a year-over-year basis during third quarter 2012 to approximately 1.6 million, according to Fitch Ratings.

The decline is largely attributable to a 62 percent year-over-year drop in prepaid net additions. In other words, not even a consumer shift of demand from postpaid to prepaid now is sufficient to propel revenues for some suppliers who specialize in prepaid services.

Wireless revenue growth will be driven more by usage based data pricing plans and increasing capabilities of smartphones as opposed to expanding the wireless subscriber base, Fitch Ratings says.

The leading U.S. mobile providers added 1.1 million revenue generating units during the thrid quarter of 2012, compared with approximately 3.3 million RGUs during the same period of 2011.

Smart phone penetration has reached 59.3 percent, an important figure because smart phone accounts drive mobile data revenue.

High speed data growth remains flat. Fitch estimates that approximately 542,000 new HSD subscribers were added by all large broadband service providers during third-quarter 2012, 3.1 percent lower than the same quarter of 2011.

Perhaps surprisingly, video now seems to be driving growth for AT&T and Verizon in the fixed network segment of their businesses.

Fitch researchers also note that the largest incumbent local-exchange carriers are successfully transforming their consumer businesses into broadband- and video-focused models, largely compensating for saturation or decline of the legacy revenue streams.

“The increasing scale of AT&T’s U-verse and Verizon’s FiOS service platforms is sufficiently

mitigating the ongoing secular and competitive pressures of their respective consumer landline

businesses and has strengthened their relative competitive position,” says Fitch.

AT&T U-verse revenues increased 38.3 percent during third-quarter 2012 when compared with the same period last year. The revenue growth is driven by higher service penetration rates along with higher levels of customers taking triple or quad play service plans.

AT&T estimates that three fourths of its U-verse TV subscribers have triple or quad play service with the company. U-verse triple play subscribers generate $170 of ARPU.

Verizon’s FiOS service accounts for 66 percent of wireline consumer revenues. Verizon’s consumer ARPU accelerated to 10.3 percent over the same quarter of 2011. Triple play customer ARPU is $150 a month.

Still, even Verizon and AT&T have to now be looking at how to sustain revenue growth when the underlying fundamentals are shifting. Subscriber growth has become a zero-sum game, though revenue growth can continue for some time, lead by mobile broadband growth.

What to do after that revenue segment slows is the current issue. As a practical matter, none of the developing new lines of business are going to contribute sizable immediate revenue. That suggests a wave of acquisitions is going to happen, as that is the most tangible way of growing subscribers.

ARPU, in that sense, will be a secondary growth driver, once mobile broadband becomes ubiquitous.

And it is starting to look as though even mobile services, which have been the growth driver for the U.S. telecommunications industry, is facing a new era, when subscriber growth in the internal market can be propped up, near term, mostly by acquiring other firms. In other words, the internal U.S. market is approaching a zero-sum game, where one carrier can gain only by taking share from another supplier.

That is one primary reason why U.S. suppliers are so interested in machine-to-machine services, as that could add unit growth from telemetry services sold to other enterprises, rather than “humans.”

Average revenue per unit is a contest at the moment. Service providers face potential erosion of voice and text messaging revenues, though that has for the most part been a muted trend in the U.S. market, as real as it has become in some other markets, particularly in Europe.

But average revenue per unit is now driven by mobile broadband, which can grow for some time, though not indefinitely. Right now, it is unit growth that is the biggest issue.

Retail net additions (postpay and prepaid net additions) for the three largest U.S. wireless service providers declined 23 percent on a year-over-year basis during third quarter 2012 to approximately 1.6 million, according to Fitch Ratings.

The decline is largely attributable to a 62 percent year-over-year drop in prepaid net additions. In other words, not even a consumer shift of demand from postpaid to prepaid now is sufficient to propel revenues for some suppliers who specialize in prepaid services.

Wireless revenue growth will be driven more by usage based data pricing plans and increasing capabilities of smartphones as opposed to expanding the wireless subscriber base, Fitch Ratings says.

The leading U.S. mobile providers added 1.1 million revenue generating units during the thrid quarter of 2012, compared with approximately 3.3 million RGUs during the same period of 2011.

Smart phone penetration has reached 59.3 percent, an important figure because smart phone accounts drive mobile data revenue.

High speed data growth remains flat. Fitch estimates that approximately 542,000 new HSD subscribers were added by all large broadband service providers during third-quarter 2012, 3.1 percent lower than the same quarter of 2011.

Perhaps surprisingly, video now seems to be driving growth for AT&T and Verizon in the fixed network segment of their businesses.

Fitch researchers also note that the largest incumbent local-exchange carriers are successfully transforming their consumer businesses into broadband- and video-focused models, largely compensating for saturation or decline of the legacy revenue streams.

“The increasing scale of AT&T’s U-verse and Verizon’s FiOS service platforms is sufficiently

mitigating the ongoing secular and competitive pressures of their respective consumer landline

businesses and has strengthened their relative competitive position,” says Fitch.

AT&T U-verse revenues increased 38.3 percent during third-quarter 2012 when compared with the same period last year. The revenue growth is driven by higher service penetration rates along with higher levels of customers taking triple or quad play service plans.

AT&T estimates that three fourths of its U-verse TV subscribers have triple or quad play service with the company. U-verse triple play subscribers generate $170 of ARPU.

Verizon’s FiOS service accounts for 66 percent of wireline consumer revenues. Verizon’s consumer ARPU accelerated to 10.3 percent over the same quarter of 2011. Triple play customer ARPU is $150 a month.

Still, even Verizon and AT&T have to now be looking at how to sustain revenue growth when the underlying fundamentals are shifting. Subscriber growth has become a zero-sum game, though revenue growth can continue for some time, lead by mobile broadband growth.

What to do after that revenue segment slows is the current issue. As a practical matter, none of the developing new lines of business are going to contribute sizable immediate revenue. That suggests a wave of acquisitions is going to happen, as that is the most tangible way of growing subscribers.

ARPU, in that sense, will be a secondary growth driver, once mobile broadband becomes ubiquitous.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

AT&T Considering Europe Market in a New Way?

Verizon Wireless, AT&T, China Mobile and mobile providers in India have advantages over suppliers in many other markets, namely a huge internal market. Some would argue that is why AT&T and Verizon have done relatively better than many European providers over the past several years, in terms of internal revenue growth.

But even a large internal market might not be sufficient to keep a very-large telecom provider growing, indefinitely. So it is that the Wall Street Journal reports AT&T is considering acquiring a European operator. The United Kingdom, Germany or the Netherlands reportedly are seen as the most-viable markets.

Whether the move is simply opportunistic, or evidence that AT&T sees some clear limits to U.S. growth, is not so clear. Some might argue European telco assets currently are undervalued, so an acquisition would be a relatively attractive way to deploy capital and gain revenue.

To be sure, the move would be a bit of a change of strategy. Obviously, AT&T and SBC had been looking at international growth opportunities for at least a decade. But up to this point, no particular deal seemed to make so much sense.

On the other hand, one might argue that AT&T has taken a hard look at its growth prospects, and does not see sufficient revenue mass from any of the new sources it is working on, compared to the advantages of "growing by acquisition."

However much AT&T might be hopeful about the new bets it is placing in applications and services, it does not currently appear that any could represent incremental revenue large enough to move the needle for AT&T, in the near term.

Have we reached a point where even a firm the size of AT&T cannot grow fast enough in the U.S. market? Possibly. The other issue is simply regulator objection. The Federal Communications Commission essentially has told AT&T, by opposing AT&T's acquisition of T-Mobile USA, that it cannot grow larger in the U.S. market.

So, like it or not, the obvious corollary is that AT&T will deploy its capital, and try to grow, elsewhere.

But even a large internal market might not be sufficient to keep a very-large telecom provider growing, indefinitely. So it is that the Wall Street Journal reports AT&T is considering acquiring a European operator. The United Kingdom, Germany or the Netherlands reportedly are seen as the most-viable markets.

Whether the move is simply opportunistic, or evidence that AT&T sees some clear limits to U.S. growth, is not so clear. Some might argue European telco assets currently are undervalued, so an acquisition would be a relatively attractive way to deploy capital and gain revenue.

To be sure, the move would be a bit of a change of strategy. Obviously, AT&T and SBC had been looking at international growth opportunities for at least a decade. But up to this point, no particular deal seemed to make so much sense.

On the other hand, one might argue that AT&T has taken a hard look at its growth prospects, and does not see sufficient revenue mass from any of the new sources it is working on, compared to the advantages of "growing by acquisition."

However much AT&T might be hopeful about the new bets it is placing in applications and services, it does not currently appear that any could represent incremental revenue large enough to move the needle for AT&T, in the near term.

Have we reached a point where even a firm the size of AT&T cannot grow fast enough in the U.S. market? Possibly. The other issue is simply regulator objection. The Federal Communications Commission essentially has told AT&T, by opposing AT&T's acquisition of T-Mobile USA, that it cannot grow larger in the U.S. market.

So, like it or not, the obvious corollary is that AT&T will deploy its capital, and try to grow, elsewhere.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Tablets ARE PCs

With talk of a "post-PC" era, the role and understanding of tablets has become a key requirement not only for device manufacturers, which face significant potential disruption of their markets, but for application providers, access providers and others in the ecosystem.

In some ways, the tablet represents a clear new appliance category. In other ways, it also displaces the use of PCs. But there remains some uncertaintly about whether the tablet is a "mobile" device or is primarily an "untethered" device.

In truth, the tablet is a mix of both. Sometimes it will be used as a "mobile" device, carried by a user outside the home, used outside the home and on a mobile network connection. Most of the time, though, it is used inside the home or office in "untethered" mode.

That leads some to note, not without justification, that a tablet is simply the latest form factor for a PC. Some might say the tablet is why "netbook" demand has collapsed, for example.

In some ways, the tablet represents a clear new appliance category. In other ways, it also displaces the use of PCs. But there remains some uncertaintly about whether the tablet is a "mobile" device or is primarily an "untethered" device.

In truth, the tablet is a mix of both. Sometimes it will be used as a "mobile" device, carried by a user outside the home, used outside the home and on a mobile network connection. Most of the time, though, it is used inside the home or office in "untethered" mode.

That leads some to note, not without justification, that a tablet is simply the latest form factor for a PC. Some might say the tablet is why "netbook" demand has collapsed, for example.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Pan-EU Telco Infrastructure Talks Are Unlikely to Succeed

Will European telcos be able to create a unified fixed nework infrastructure across borders? Fitch Ratings doesn't think so.

The proposal, which presumably would have to be ratified and approved by the European Commission, would allow all the contestants to essentially create a continent-wide infrastructure company that would sell capacity and services to any retail operator in any of the participating countries.

If you think about it, this is a bigger version of the infrastructure sharing mobile operators have been doing: sharing towers and sometimes radio infrastructure in ways that lower costs for each of the retail providers.

Doubtless there are pragmatic difficulties, such as technology incompatibilities in some cases. But Fitch thinks the bigger problem simply will be EC regulator opposition to a move very likely seen as the precursor to more consolidation in the EC telecom markets.

Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Telecom Italia, Telefonica, Belgacom and KPN are among the carriers interested in such a cross-country infrastructure sharing plan. The sharing might not be seen as "consolidation" in the market by some. But regulators might not agree.

The proposal, which presumably would have to be ratified and approved by the European Commission, would allow all the contestants to essentially create a continent-wide infrastructure company that would sell capacity and services to any retail operator in any of the participating countries.

If you think about it, this is a bigger version of the infrastructure sharing mobile operators have been doing: sharing towers and sometimes radio infrastructure in ways that lower costs for each of the retail providers.

Doubtless there are pragmatic difficulties, such as technology incompatibilities in some cases. But Fitch thinks the bigger problem simply will be EC regulator opposition to a move very likely seen as the precursor to more consolidation in the EC telecom markets.

Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Telecom Italia, Telefonica, Belgacom and KPN are among the carriers interested in such a cross-country infrastructure sharing plan. The sharing might not be seen as "consolidation" in the market by some. But regulators might not agree.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Do Smart Phones and Tablet Change Demand for "Remote Management of Home" Services

Though consumers often indicate they will do something, and then do not, or say they will not do something, and then do, it is possible that widespread adoption of smart phones and tablets, plus more sophisticated and Web-accessible management tools, could change the perception of home security and remote monitoring services, a study by Strategy Analytics suggests. .

The survey of broadband households in France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and United States found that more than 50 percent of broadband households without security are willing to pay for professionally monitored services, if combined with monitoring and control capabilities.

The key change there probably are the remote control features, not the security as such.

The study also revealed significant willingness to pay for remote healthcare and energy management services if the services are priced right. Potential adoption of smart home services is highest in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Italy and less so in France.

Remote healthcare services have the greatest potential in Italy if recurring fees are kept under $10 per month.

"The percentage of broadband households with both the interest in and willingness to pay for selected connected home solutions is higher than expected," said Bill Ablondi, Strategy Analytics director.

The study might suggest a combination of smart phone and tablet usage, plus easier to use Web tools, could be changing customer appetite for new home management services, such as controlling heating and cooling systems or other appliances within the home, for example.

Percentage of Broadband Households Willing to Pay for Selected Smart Home Capabilities in the US and Major Western European Countries

Source: Strategy Analytics, Inc.

The survey of broadband households in France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and United States found that more than 50 percent of broadband households without security are willing to pay for professionally monitored services, if combined with monitoring and control capabilities.

The key change there probably are the remote control features, not the security as such.

The study also revealed significant willingness to pay for remote healthcare and energy management services if the services are priced right. Potential adoption of smart home services is highest in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Italy and less so in France.

Remote healthcare services have the greatest potential in Italy if recurring fees are kept under $10 per month.

"The percentage of broadband households with both the interest in and willingness to pay for selected connected home solutions is higher than expected," said Bill Ablondi, Strategy Analytics director.

The study might suggest a combination of smart phone and tablet usage, plus easier to use Web tools, could be changing customer appetite for new home management services, such as controlling heating and cooling systems or other appliances within the home, for example.

Percentage of Broadband Households Willing to Pay for Selected Smart Home Capabilities in the US and Major Western European Countries

| Percentage Willing to Pay | |

| Self-monitored Security | 55 percent |

| Professionally Monitored Security | 54 percent |

| Remote Monitoring and Control | 47 percent |

| Remote Healthcare Services | 32 percent |

| Remote Energy Management | 30 percent |

Source: Strategy Analytics, Inc.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Small Cell "As a Service?"

European service provider Colt is among service providers who believe a wholesale approach to small cell infrastructure makes sense. Virgin Business Media also is among service providers who believe creating a network of small cells and then selling use of that network to other mobile service providers, is a business opportunity.

There are any number of reasons why some mobile service providers might find the “buy rather than build” approach attractive. The cost of backhaul for a small cell will be a challenging exercise.

Whichever technology is used to backhaul small cells, it has to be cheap, "it has to be massively cheap," said Andy Sutton, Everything Everywhere principal architect, access transport. "We have a financial envelope for small cells and it's challenging."

Cost is so important because small cells will have relatively low usage compared to a macrocell and there will be lots of sites to support. Compared with macrocells, small cells quite frequently will cover distances of about 50 square meters or 538 square feet. That's an area about 23 feet by 23 feet.

One way to look at matters is that this is an area smaller than the range of a consumer's home Wi-Fi router. In other cases service providers might need to support coverage of 2 kilometers down to 200 meters. Traditional backhaul might well make sense where a small cell covers an area of 2 kilometers radius.

It will be substantially more challenging for cells covering 200 meters or less. Cells covering areas smaller than that will be much more challenged, in terms of how much a service provider can afford to invest, in terms of radio and associated facilities, or the recurring cost of leased bandwidth.

Backhaul cost therefore becomes a key operating cost issue. A network services provider that owns lots of metro fiber, a cable operator or a telco might well be able to supply the affordable connections such small cells will require.

Entities that do not own such assets will find the cost of leasing backhaul, not to mention the costs of radios and site infrastructure, to be quite challenging as well.

For all those reasons, a well-developed wholesale small cell network could well make sense, especially for mobile service providers without extensive fixed network assets in an area.

Some will be unable to resist calling such services "small cell infrastructure as a service." Of course, historically, virtually all telecommunications offerings have been "services." So the term means almost nothing. The classic case of "communications as a product" are business phone systems.

Some speak of "communications as a service," which, when you think about it, is nonsensical. Communications always has been a service (with the exception of business phone systems). It is "communications as an app," or "communications as a feature," that is new.

In that sense, there is clear logic for small cell wholesale, in many cases. We just shouldn't get caught up in nonsensical nomenclature games.

There are any number of reasons why some mobile service providers might find the “buy rather than build” approach attractive. The cost of backhaul for a small cell will be a challenging exercise.

Whichever technology is used to backhaul small cells, it has to be cheap, "it has to be massively cheap," said Andy Sutton, Everything Everywhere principal architect, access transport. "We have a financial envelope for small cells and it's challenging."

Cost is so important because small cells will have relatively low usage compared to a macrocell and there will be lots of sites to support. Compared with macrocells, small cells quite frequently will cover distances of about 50 square meters or 538 square feet. That's an area about 23 feet by 23 feet.

One way to look at matters is that this is an area smaller than the range of a consumer's home Wi-Fi router. In other cases service providers might need to support coverage of 2 kilometers down to 200 meters. Traditional backhaul might well make sense where a small cell covers an area of 2 kilometers radius.

It will be substantially more challenging for cells covering 200 meters or less. Cells covering areas smaller than that will be much more challenged, in terms of how much a service provider can afford to invest, in terms of radio and associated facilities, or the recurring cost of leased bandwidth.

Backhaul cost therefore becomes a key operating cost issue. A network services provider that owns lots of metro fiber, a cable operator or a telco might well be able to supply the affordable connections such small cells will require.

Entities that do not own such assets will find the cost of leasing backhaul, not to mention the costs of radios and site infrastructure, to be quite challenging as well.

For all those reasons, a well-developed wholesale small cell network could well make sense, especially for mobile service providers without extensive fixed network assets in an area.

Some will be unable to resist calling such services "small cell infrastructure as a service." Of course, historically, virtually all telecommunications offerings have been "services." So the term means almost nothing. The classic case of "communications as a product" are business phone systems.

Some speak of "communications as a service," which, when you think about it, is nonsensical. Communications always has been a service (with the exception of business phone systems). It is "communications as an app," or "communications as a feature," that is new.

In that sense, there is clear logic for small cell wholesale, in many cases. We just shouldn't get caught up in nonsensical nomenclature games.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

U.S. Mobile Payments in 2017 Equally Split Between Retail an Remote Payments

The volume of U.S. mobile payments will reach $90 billion in 2017, a 48 percent compound annual growth rate rom the $12.8 billion worth of mobile purchases in 2012, according to Forrester Research analyst Denée Carrington.

Mobile proximity payments (retail transactions) are currently the smallest category within mobile payments, but Carrington expects it to be the fastest growing category. Proximity payments will reach $41 billion by 2017, making up nearly half of all mobile payments in 2017.

Cross-border remittances using peer-to-peer networks either for bill payment or sending money to other people, will exceed $4 billion in remittance value over the next five years but will fail to achieve the scale of mobile proximity payments or mobile commerce, Carrington forecasts.

Mobile remote payments, which Forrester Research calls “mobile commerce,” represent 90 percent of the mobile payments category and will continue to be the most-dominant category, representing about $45 billion in transaction volume.

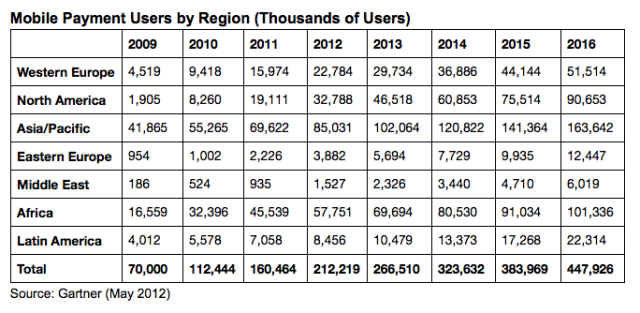

Analysts at Gartner in 2012 had a similar range of forecasts.

Mobile proximity payments (retail transactions) are currently the smallest category within mobile payments, but Carrington expects it to be the fastest growing category. Proximity payments will reach $41 billion by 2017, making up nearly half of all mobile payments in 2017.

Cross-border remittances using peer-to-peer networks either for bill payment or sending money to other people, will exceed $4 billion in remittance value over the next five years but will fail to achieve the scale of mobile proximity payments or mobile commerce, Carrington forecasts.

Mobile remote payments, which Forrester Research calls “mobile commerce,” represent 90 percent of the mobile payments category and will continue to be the most-dominant category, representing about $45 billion in transaction volume.

Analysts at Gartner in 2012 had a similar range of forecasts.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

If E-Commerce is So Disruptive, How Come More Retailers Have Not Failed?

Apparently, attendance is up smartly at the National Retail Federation meeting this year, with about a 60 percent increase in attendance by retailers looking for technology to improve competitiveness in the face of online and mobile challenges.

But there is a lesson here. Firms such Amazon have been in business since 1994. Everybody seems aware of e-commerce. A growing amount of retail sales volume passes through Internet retailer channels. And yet, it is hard to point to major retailer disruption, in the form of firms going out of business.

“If e-business is so disruptive, how come nobody died?” Gartner analyst Mark Raskino recalls thinking, back in 2000. The answer might be, as it often seems to be, that big trends in complex ecosystems take some time to take root, and then hit an inflection point.

It is quite possible that U.S. retailers sense an inflection point coming, where mobile commerce or e-commerce will cease to be an irritant, and start to be extremely disruptive, dramatically reshaping revenue patterns.

If and when that happens, the feared wave of bankruptcies will happen. The fact that nothing quite unusual seems to have happened, on that score, is simply the period of ecosystem change that precedes the disruption, one might argue.

But there is a lesson here. Firms such Amazon have been in business since 1994. Everybody seems aware of e-commerce. A growing amount of retail sales volume passes through Internet retailer channels. And yet, it is hard to point to major retailer disruption, in the form of firms going out of business.

“If e-business is so disruptive, how come nobody died?” Gartner analyst Mark Raskino recalls thinking, back in 2000. The answer might be, as it often seems to be, that big trends in complex ecosystems take some time to take root, and then hit an inflection point.

It is quite possible that U.S. retailers sense an inflection point coming, where mobile commerce or e-commerce will cease to be an irritant, and start to be extremely disruptive, dramatically reshaping revenue patterns.

If and when that happens, the feared wave of bankruptcies will happen. The fact that nothing quite unusual seems to have happened, on that score, is simply the period of ecosystem change that precedes the disruption, one might argue.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Mobile Internet Users in China are 75% of Total

At the end of December 2012, there were about 564 million Internet users in China. There were about 420 million mobile Internet users, representing about 74.5 percent of all Internet users, according to the China Internet Development report.

If you want to know why, sooner or later, Apple will have to create a lower-cost iPhone, that's the reason. Right now, three quarters of Internet users in China use mobile. And, right, now, most of those users own an Android device.

It isn't any more complicated than that. Apple has done quite well, globally, in dominating the high end portion of the smart phone market.

But to put it colloquially, Apple now is running out of high end customers. Most of the rest of the market will be more mainstream. So unless Apple wants to settle for low growth, it has to extend its product line, as it has with MP3 players and tablets, to reach a more mainstream user who does not want to buy, or cannot afford to buy, Apple's top of the line device.

If you want to know why, sooner or later, Apple will have to create a lower-cost iPhone, that's the reason. Right now, three quarters of Internet users in China use mobile. And, right, now, most of those users own an Android device.

It isn't any more complicated than that. Apple has done quite well, globally, in dominating the high end portion of the smart phone market.

But to put it colloquially, Apple now is running out of high end customers. Most of the rest of the market will be more mainstream. So unless Apple wants to settle for low growth, it has to extend its product line, as it has with MP3 players and tablets, to reach a more mainstream user who does not want to buy, or cannot afford to buy, Apple's top of the line device.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Google, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo Sliding into "Personal Assistant" Function, Business

For years, it has been difficult to "classify" Google. Google says it is a technology company, and with its expanding role in smart phones, tablets, operating systems, its core search business, mobile commerce, navigation and browsers, that certainly is true.

On the other hand, Google is the paramount example of a big, influential technology company whose revenue stream is based on advertising services. That always throws a monkey wrench into the taxonomy, since historically, "media" firms had that revenue model.

For other firms, such as Facebook or Twitter, the taxonomy is not quite so difficult. The content those firms "create" might be contributed by users, but there is a reason firms such as Facebook and Twitter are known as "social media."

They are more recognizably "media."

These days, it also is noted that Apple's Siri, use of mobile devices overall, Twitter and Facebook are "threats" to Google because they are alternate ways for people to "discover or find things."

In other words, Twitter, Facebook and other apps are challengers to Google as rival ways for people to discover, find or locate content and information that is highly relevant to them.

“When there is too much information, there high value in search, navigation and discovery,” said venture capitalitst Bill Tai.

Mobile highlights the changing context of "search," though. As it turns out, what people "search for," in a mobile context, already shows a bias towards commerce: places to go, things to do, places to shop or buy products. That drives local search and mobile commerce.

But maybe something else is happening to search as well. Voice search might be more than just "another input option." Maybe it is something more like a "digital personal assistant," allowing people to quickly find answers to questions.

Yes, that means people use the feature to find things, which is a search or discovery process. But one might argue it is more: a move by a variety of apps, tools and approaches towards a personalized "digital assistant for your life" approach that some have called the "remote control for your life."

In that sense, it would be easier to categorize firms with ad-based revenue models. They all are in the evolving "personal digital assistant" business.

On the other hand, Google is the paramount example of a big, influential technology company whose revenue stream is based on advertising services. That always throws a monkey wrench into the taxonomy, since historically, "media" firms had that revenue model.

For other firms, such as Facebook or Twitter, the taxonomy is not quite so difficult. The content those firms "create" might be contributed by users, but there is a reason firms such as Facebook and Twitter are known as "social media."

They are more recognizably "media."

These days, it also is noted that Apple's Siri, use of mobile devices overall, Twitter and Facebook are "threats" to Google because they are alternate ways for people to "discover or find things."

In other words, Twitter, Facebook and other apps are challengers to Google as rival ways for people to discover, find or locate content and information that is highly relevant to them.

“When there is too much information, there high value in search, navigation and discovery,” said venture capitalitst Bill Tai.

Mobile highlights the changing context of "search," though. As it turns out, what people "search for," in a mobile context, already shows a bias towards commerce: places to go, things to do, places to shop or buy products. That drives local search and mobile commerce.

But maybe something else is happening to search as well. Voice search might be more than just "another input option." Maybe it is something more like a "digital personal assistant," allowing people to quickly find answers to questions.

Yes, that means people use the feature to find things, which is a search or discovery process. But one might argue it is more: a move by a variety of apps, tools and approaches towards a personalized "digital assistant for your life" approach that some have called the "remote control for your life."

In that sense, it would be easier to categorize firms with ad-based revenue models. They all are in the evolving "personal digital assistant" business.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Monday, January 14, 2013

"Year of the Phablet?"

One informal rule of thumb that works pretty well is to assume that whenever an analyst dubs the coming year the "year of," it will not be. That doesn't mean the trend is wrong. Typically, there is a fair chance a trend, or potential trend, is at work.

The issue is just that a big trend takes a while to get established, and analysts typically are, for professional reasons, too eager to declare that a new trend not only will begin, but will be consequential, in the next 12-month period.

"Phablets" now have been pronounced the subject of such a "year of" prediction for 2013. By contrarian thinking, that might suggest 2013, in fact, will not be as consequential as predicted.

The Asia-Pacific is, and will remain, the world's biggest market for phablets, says Joshua Flood, ABI Research senior analyst.

The Asia-Pacific is, and will remain, the world's biggest market for phablets, says Joshua Flood, ABI Research senior analyst.

Last year, the Asia-Pacific region absorbed 42 percent of global shipments, a proportion that will expand steadily over the next few years to account for over 50 percent of shipments by 2017, according to ABI Research.

But some analysts continue to think the problem is that phablets are "too big for a smart phone, and too small for a tablet." The key is ergonomics, some would argue. At some point, a smart phone has to be held in one hand.

But is it a phone? The point is not whether the device can make and receive calls, or send and receive text messages. In fact, most communicating appliances can do such things. The issue is whether the lead app for a smart phone will always be "making calls."

These days, most users probably spend more time using a smart phone as an Internet device, for browsing, playing games, sending text messages or consuming media.

It is a reasonable objection that most people would find a phablet a less convenient operation than using a smaller smart phone. But for many users, "making a call" might be only the fourth or fifth most frequent use of the device.

We will find out, eventually. We probably won't find out in 2013, though.

The issue is just that a big trend takes a while to get established, and analysts typically are, for professional reasons, too eager to declare that a new trend not only will begin, but will be consequential, in the next 12-month period.

"Phablets" now have been pronounced the subject of such a "year of" prediction for 2013. By contrarian thinking, that might suggest 2013, in fact, will not be as consequential as predicted.

Last year, the Asia-Pacific region absorbed 42 percent of global shipments, a proportion that will expand steadily over the next few years to account for over 50 percent of shipments by 2017, according to ABI Research.

But some analysts continue to think the problem is that phablets are "too big for a smart phone, and too small for a tablet." The key is ergonomics, some would argue. At some point, a smart phone has to be held in one hand.

But is it a phone? The point is not whether the device can make and receive calls, or send and receive text messages. In fact, most communicating appliances can do such things. The issue is whether the lead app for a smart phone will always be "making calls."

These days, most users probably spend more time using a smart phone as an Internet device, for browsing, playing games, sending text messages or consuming media.

It is a reasonable objection that most people would find a phablet a less convenient operation than using a smaller smart phone. But for many users, "making a call" might be only the fourth or fifth most frequent use of the device.

We will find out, eventually. We probably won't find out in 2013, though.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

New Roles for Retail Wi-Fi

Getting the mobile strategy right can make a big difference for retailers, said Alison Paul, leader of Deloitte's retail and distribution practice.

When consumers use mobile devices in physical stores, there is a 72 percent chance they will turn their browsing into actual purchases, a 14 percent increase above those who don't use mobile devices, Paul said. Wi-Fi therefore plays a new role in converting interest into purchases.

Up to this point,Wi-Fi has been an amenity for retailers in verticals such as food and beverage, the perhaps-classic case being Starbucks. Now Wi-Fi is being viewed by a wider range of retailers who have to balance a legitimate fear of encouraging "showrooming" with the possible upside of tailoring their in-store Wi-Fi networks to encourage purchases while users are inside the stores.

That might include any number of ways to try and influence consumers while they are shopping, from showing past buying history, delivering coupons or information about specials, for example.

The business model also is different. Rather than an indirect amenity designed to increase customer dwell time, and therefore sales, the new approach attempts to directly influence shopping behavior.

According to an analysis by researchers at Deloitte, mobile (defined as smart phones

for this analysis) influences 5.1 percent of all retail store sales in the United States. That implies

about $159 billion in sales for 2012.

Mobile influence is anticipated to grow exponentially to 17 to 21 percent of total retail sales, amounting to $628 to $752 billion in mobile-influenced store sales by 2016.

When consumers use mobile devices in physical stores, there is a 72 percent chance they will turn their browsing into actual purchases, a 14 percent increase above those who don't use mobile devices, Paul said. Wi-Fi therefore plays a new role in converting interest into purchases.

Up to this point,Wi-Fi has been an amenity for retailers in verticals such as food and beverage, the perhaps-classic case being Starbucks. Now Wi-Fi is being viewed by a wider range of retailers who have to balance a legitimate fear of encouraging "showrooming" with the possible upside of tailoring their in-store Wi-Fi networks to encourage purchases while users are inside the stores.

That might include any number of ways to try and influence consumers while they are shopping, from showing past buying history, delivering coupons or information about specials, for example.

The business model also is different. Rather than an indirect amenity designed to increase customer dwell time, and therefore sales, the new approach attempts to directly influence shopping behavior.

According to an analysis by researchers at Deloitte, mobile (defined as smart phones

for this analysis) influences 5.1 percent of all retail store sales in the United States. That implies

about $159 billion in sales for 2012.

Mobile influence is anticipated to grow exponentially to 17 to 21 percent of total retail sales, amounting to $628 to $752 billion in mobile-influenced store sales by 2016.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Fixed Version of LTE Coming from AT&T

Both Verizon and AT&T have signaled willingness to use Long Term Evolution networks to deliver higher-speed broadband access to customers in rural areas. Verizon already does so, selling its "Home Fusion" product.

Now AT&T executives are sending clearer signals that AT&T plans to do the same.

"We anticipate that LTE will be a broadband coverage solution for a portion of the country; we just haven't yet gotten to the point where we have enough experience under our belt to know exactly what that footprint is going to be," said John Donovan, senior executive vice president of AT&T Technology and Network Operations.

Tariffs will be an issue. It is almost unthinkable that the tariffs for Long Term Evolution, used as a substitute for a fixed broadband connection, will be closely equivalent. Consider that mobile broadband services feature single-digit usage plans, where fixed network broadband services have triple-digit caps.

Verizon's Home Fusion service, which also uses the LTE network to deliver fixed location broadband, features a few monthly service plans, starting at $60 a month (10 gigabyte cap).

The 20 gigabyte plan sells for $90 per month, while the 30 gigabyte plan sells for $120 per month. Under any circumstances, the usage caps for Home Fusion and FiOS fixed network broadband vary by an order of magnitude.

Many observers will suggest the future AT&T product, as well as Home Fusion, are aimed primarily at rural and other customers who do not have access to faster fixed network access alternatives.

The direct competitors, in other words, are satellite broadband services, dial-up access or slower digital subscriber line networks. Some might argue that were cable modem services are available, most consumers will choose that service.

According to a Federal Communications Commission study, about five percent of U.S. homes cannot buy fixed network service from any provider.

Now AT&T executives are sending clearer signals that AT&T plans to do the same.

"We anticipate that LTE will be a broadband coverage solution for a portion of the country; we just haven't yet gotten to the point where we have enough experience under our belt to know exactly what that footprint is going to be," said John Donovan, senior executive vice president of AT&T Technology and Network Operations.

Tariffs will be an issue. It is almost unthinkable that the tariffs for Long Term Evolution, used as a substitute for a fixed broadband connection, will be closely equivalent. Consider that mobile broadband services feature single-digit usage plans, where fixed network broadband services have triple-digit caps.

Verizon's Home Fusion service, which also uses the LTE network to deliver fixed location broadband, features a few monthly service plans, starting at $60 a month (10 gigabyte cap).

The 20 gigabyte plan sells for $90 per month, while the 30 gigabyte plan sells for $120 per month. Under any circumstances, the usage caps for Home Fusion and FiOS fixed network broadband vary by an order of magnitude.

Many observers will suggest the future AT&T product, as well as Home Fusion, are aimed primarily at rural and other customers who do not have access to faster fixed network access alternatives.

The direct competitors, in other words, are satellite broadband services, dial-up access or slower digital subscriber line networks. Some might argue that were cable modem services are available, most consumers will choose that service.

According to a Federal Communications Commission study, about five percent of U.S. homes cannot buy fixed network service from any provider.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Sunday, January 13, 2013

Developed World Broadband, Voice Prices are Rising

Given the trend of falling prices for high-speed access and voice that have occurred in most markets over the last decade or two, some might wonder whether there is any end to the trend. The answer, surprisingly, might be "yes," at least for broadband access, and in part for some voice services.

U.S. broadband access retail prices have been relatively stable since about 2010, including both triple play packages and stand-alone retail prices for broadband access, though speeds for same-price services tend to grow.

But there now are signs that broadband and even voice prices in the U.S. market, and elsewhere in developed markets, are growing, not shrinking.

Cablevision, for example, is boosting prices about $4 a month. Time Warner Cable added about a $5 a month modem rental fee late in 2012. In the United Kingdom, Virgin Media also is raising prices, both for high-speed access and voice services.

In Australia, Optus likewise has hiked prices. In the United Kingdom, BT also is raising prices for broadband access and voice services.

That is a significant difference from what is happening in most other areas of the developing world, where prices for broadband and voice traditionally have been quite high, compared to developed nations.

One might argue that prices in developed markets are growing because upgrades of networks to support hundreds of megabits up to 1-Gbps speeds now are happening, with the resultant need to boost prices for those features.

By some studies, developed nation prices already were quite low, measured in local terms as a percentage of income.

U.S. broadband access retail prices have been relatively stable since about 2010, including both triple play packages and stand-alone retail prices for broadband access, though speeds for same-price services tend to grow.

But there now are signs that broadband and even voice prices in the U.S. market, and elsewhere in developed markets, are growing, not shrinking.

Cablevision, for example, is boosting prices about $4 a month. Time Warner Cable added about a $5 a month modem rental fee late in 2012. In the United Kingdom, Virgin Media also is raising prices, both for high-speed access and voice services.

In Australia, Optus likewise has hiked prices. In the United Kingdom, BT also is raising prices for broadband access and voice services.

That is a significant difference from what is happening in most other areas of the developing world, where prices for broadband and voice traditionally have been quite high, compared to developed nations.

One might argue that prices in developed markets are growing because upgrades of networks to support hundreds of megabits up to 1-Gbps speeds now are happening, with the resultant need to boost prices for those features.

By some studies, developed nation prices already were quite low, measured in local terms as a percentage of income.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Despite Changing Device Preferences, Cloud App Trend is Key

With all the attention now paid to changing device preferences, it sometimes is hard to remember that “client” device preferences only emphasize the growing shift to cloud-based apps and behavior.

Apps related to use of maps provide one example, but only one. Though sales of dedicated global positioning satellite units are growing slowly, use of web-based maps and “directions” are up about 20 percentage points since 2010 according to an Accenture study.

Almost half (47 percent) of consumers Accenture surveyed use global positioning in a typical week.

Some 69 percent use a PC, 48 percent use a mobile device or smart phone and 13 percent use a tablet;

Some 35 percent have a factory-installed GPS device in their car and 43 percent would like to have a GPS device installed in their next car, the study suggests.

The point is that, while the GPS device is highly popular, its preferred form is now in a software app on amulti-function device.

But similar shifts are occurring around use of other apps as well. A significant increase in use of online services has occurred in just one year, the study suggests.

In fact, usage of cloud apps increased for all eight of the online services Accenture researchers asked about, including online email services, games, photo storage, movie streaming, data backup, music streaming,calendaring and document creation.

Apps related to use of maps provide one example, but only one. Though sales of dedicated global positioning satellite units are growing slowly, use of web-based maps and “directions” are up about 20 percentage points since 2010 according to an Accenture study.

Almost half (47 percent) of consumers Accenture surveyed use global positioning in a typical week.

Some 69 percent use a PC, 48 percent use a mobile device or smart phone and 13 percent use a tablet;

Some 35 percent have a factory-installed GPS device in their car and 43 percent would like to have a GPS device installed in their next car, the study suggests.

The point is that, while the GPS device is highly popular, its preferred form is now in a software app on amulti-function device.

But similar shifts are occurring around use of other apps as well. A significant increase in use of online services has occurred in just one year, the study suggests.

In fact, usage of cloud apps increased for all eight of the online services Accenture researchers asked about, including online email services, games, photo storage, movie streaming, data backup, music streaming,calendaring and document creation.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Saturday, January 12, 2013

What Follows Momentous First Decade of 21st Century?

Without question, the first decade of the 21st century has been momentous, in terms of the broader telecommunications industry, and especially in terms of use of mobile services. Usage in the U.S. market, for example, grew from about 38 percent of the population to 93 percent.

And though consumers had started using text messaging at the beginning of that decade, use of mobile Internet access services was nil. So, on three scores, use of mobility changed drastically.

For starters, mobile usage became virtually ubiquitous. That had obvious impact on demand for alternative ways of making phone calls.

But text messaging, which almost nobody did in 2000, became a normal method of communications, again displacing a significant amount of voice activity.

And only quite recently have users begun to use their mobiles as an Internet access method.

That stunning change in consumer behavior also happened elsewhere around the world. From about 15 percent global penetration, adoption of wireless had surpassed 86 percent by 2011, worldwide.

But such growth rates come at a "price," namely that once markets become saturate, service providers have to look elsewhere for a second act. And that largely is the main story in telecommunications in the second decade of the 21st century.

Consider growth rates for fixed network broadband, which had a global growth rate of about 75 percent from 2001 to 2002. Growth began to slow in each succeeding year, dropping to about 10 percent annual growth rates between 2010 and 2011.

Fixed network voice lines, which had been growing at very low, single digit rates, went negative, globally, between 2006 and 2007.

Use of mobile broadband, which had been negligible through 2006, suddenly exploded in 2007, and currently represent the growth driver for the entire global communications business, with rates of change in the 40 percent range, for 2010 to 2011.

But you know what comes next. Mobile broadband, in turn, will reach saturation, probably settling into an intermediate growth rate of perhaps 10 percent a year.

Nobody knows what will come next, which is one reason why service providers are placing lots of bets in a lots of areas. The next big thing after mobile broadband is not yet "discovered."

Oddly enough, because of such huge success in the first decade of the 21st century, the second decade will likely to be a time when global communications revenue growth could slow, dramatically, unless huge new replacement revenue streams are discovered.

In fact, on a global basis, mobile subscription growth rates seem to have peaked between 2005 and 2007.

And though consumers had started using text messaging at the beginning of that decade, use of mobile Internet access services was nil. So, on three scores, use of mobility changed drastically.

For starters, mobile usage became virtually ubiquitous. That had obvious impact on demand for alternative ways of making phone calls.

But text messaging, which almost nobody did in 2000, became a normal method of communications, again displacing a significant amount of voice activity.

And only quite recently have users begun to use their mobiles as an Internet access method.

That stunning change in consumer behavior also happened elsewhere around the world. From about 15 percent global penetration, adoption of wireless had surpassed 86 percent by 2011, worldwide.

But such growth rates come at a "price," namely that once markets become saturate, service providers have to look elsewhere for a second act. And that largely is the main story in telecommunications in the second decade of the 21st century.

Consider growth rates for fixed network broadband, which had a global growth rate of about 75 percent from 2001 to 2002. Growth began to slow in each succeeding year, dropping to about 10 percent annual growth rates between 2010 and 2011.

Fixed network voice lines, which had been growing at very low, single digit rates, went negative, globally, between 2006 and 2007.

Use of mobile broadband, which had been negligible through 2006, suddenly exploded in 2007, and currently represent the growth driver for the entire global communications business, with rates of change in the 40 percent range, for 2010 to 2011.

But you know what comes next. Mobile broadband, in turn, will reach saturation, probably settling into an intermediate growth rate of perhaps 10 percent a year.

Nobody knows what will come next, which is one reason why service providers are placing lots of bets in a lots of areas. The next big thing after mobile broadband is not yet "discovered."

Oddly enough, because of such huge success in the first decade of the 21st century, the second decade will likely to be a time when global communications revenue growth could slow, dramatically, unless huge new replacement revenue streams are discovered.

In fact, on a global basis, mobile subscription growth rates seem to have peaked between 2005 and 2007.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Friday, January 11, 2013

Netflix "Open Connect" CDN is Getting Traction

Netflix Open Connect, the single purpose video content delivery network launched last year, is now delivering the majority of Netflix international traffic and is growing at a rapid pace in the domestic market, Netflix says.

That might come as a surprise for some who had predicted failure for Netflix as a provider of its own direct content delivery network services. Perhaps Open Connect has had only a marginal financial impact on other retail CDNs, but that probably was not the Netflix objective, in any case.

The objective was, and is, better end user experience, not revenue or Netflix operating costs.

In early 2012 Netflix began enabling Internet service providers to receive, at no cost to them, Netflix video directly at the interconnection point of the ISP’s choice.

By connecting directly through Open Connect, ISPs would be able to improve quality of experience.

Netflix now says Open Connect is "widely deployed around the world, serving the vast majority of Netflix video in Europe, Canada and Latin America, and a growing proportion in the U.S., where Netflix has over 25 million streaming members."

Cablevision, Virgin Media, British Telecom, Telmex, Telus, TDC and GVT are among ISPs using Open Connect.

Preference for private CDNs, rather than buying service from a retail CDN services provider, is becoming a more popular option for large application providers, such as Comcast, Google, Apple or Facebook. Amazon of course can use its own CDN service, which is available as a retail offering for third parties.

That might come as a surprise for some who had predicted failure for Netflix as a provider of its own direct content delivery network services. Perhaps Open Connect has had only a marginal financial impact on other retail CDNs, but that probably was not the Netflix objective, in any case.

The objective was, and is, better end user experience, not revenue or Netflix operating costs.

In early 2012 Netflix began enabling Internet service providers to receive, at no cost to them, Netflix video directly at the interconnection point of the ISP’s choice.

By connecting directly through Open Connect, ISPs would be able to improve quality of experience.

Netflix now says Open Connect is "widely deployed around the world, serving the vast majority of Netflix video in Europe, Canada and Latin America, and a growing proportion in the U.S., where Netflix has over 25 million streaming members."

Cablevision, Virgin Media, British Telecom, Telmex, Telus, TDC and GVT are among ISPs using Open Connect.

Preference for private CDNs, rather than buying service from a retail CDN services provider, is becoming a more popular option for large application providers, such as Comcast, Google, Apple or Facebook. Amazon of course can use its own CDN service, which is available as a retail offering for third parties.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Amazon "Mobile First" Efforts

Amazon's mobile efforts span a range of initiatives, as illustrated by Business Insider, including e-readers, tablets, the Amazon Appstore, Kindle content and possibly mobile advertising or smart phones.

Some would note that Amazon already has been successful in moving into the mobile commerce realm.

Amazon and Apple arguably will compete more directly, in the mobile realm, based on their commerce efforts, while Google and Facebook will compete more directly in advertising and promotion elements of the mobile business, one might argue.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.