SK Telecom, KT and LG Uplus in South Korea are launching “joyn” services to combat inroads being made by over the top messaging services. At first, each carrier will operate joyn as a service available only to users of its own network, but interoperability between the three carriers is expected in 2013.

Joyn, the brand created to support Rich Communication Services (RCS), allows customers to make Internet-based voice calls and video calls and send chat messages as well. Joyn supports individual and group messages of up to 5,000 characters,, Yonhap news service reports.

In South Korea, KakaoTalk is among the rival services mobile service providers must contend with.

The service is initially available on 22 different types of Android phones, and can be downloaded from each operator’s app store for free. SKT says it will announce extended Android support and an iOS version early in 2013.

Messages to non-users will be sent as text messages, as is the case with Apple’s iMessage service, while a PC-based version is slated to launch in Korea in the first quarter of the new year.

SKT says the service will be free for users of its flat-rate 3G and LTE tariffs. For all other customers, chat and text messages will be charged at 20 won ($0.02) and video calling upwards of 0.6 won per second (that’s circa $0.03 per minute).

Some think joyn will face major obstacles. KakaoTalk has more than 70 million users worldwide and, in its native Korea, is installed on more than 90 percent of the country’s smart phones.

Smartphone messaging apps are hugely popular across Asia. Alongside KakaoTalk, China’s WeChat (near-300 million users) and Japan’s Line (85 million) have grown massively in 2012. Of course, the issue is less the installed base of apps but the volume of WhatsApp messages being sent and received by mobile users.

But not all mobile service providers seem to think joyn is the more profitable way to compete in the messaging market. The logic is simply that the OTT apps already have achieved such large installed base and scale that any new entrant will have trouble dislodging users.

Indonesian carrier Telkomsel in fact has partnered with Kakao Talk, rather than participaing in the joyn effort. But it would be fair to argue that most service providers will try joyn.

In Spain, Movistar, Orange and Vodafone, Spain's three leading mobile service providers, have launched "Rich Communication Services" using the joyn brand.

Spain has been the first country in the world to offer a fully interoperable carrier-owned over the top voice and messaging app, meaning that any customers of any of the mobile service providers can communicate with each other.

In Germany, Deutsche Telekom and Vodafone both support joyn, and the leading South Korean mobile operators appear to be following that approach as well.

The idea is that joyn will allow mobile service provides to create a very large community of users, with access to "rich" voice and messaging ("rich" generally implies support for video) features. That scale effect might ultimately be crucial for joyn success, as well as the ability of mobile service providers to blunt the over the top messaging app attack.

There are about three or four different ways mobile service providers globally can react to over the top messaging.

About half the options are hostile or unfriendly to the consumer. Carriers can block use of over the top apps, or charge extra fees for people who use the generally free apps. Neither of those approaches are especially desirable in competitive markets where another provider will avoid blocking or charging.

There are two approaches that are less surly ways of approaching the problem. Joyn is one way of competing with a carrier-owned alternative intended from the start to be a "third party" brand.

In other cases, carriers have created their own branded OTT apps. The level of competition in a given market tends to suggest whether mobile service providers should offer their own OTT apps, or avoid doing so.

In markets where voice and messaging revenue already is sharply declining, competing might be the only choice. In other markets, where there is less pressure, service providers generally will resist jumping into branded OTT voice and messaging apps, to avoid cannibalizing carrier voice and messaging.

In other cases, as with Verizon Wireless, carriers simply offer unlimited domestic calling and texting as a basic network access fee, to undercut the value proposition of the "free" OTT apps. That arguably works best where there is a very-large internal calling market.

Wednesday, December 26, 2012

South Korean Mobile Ops Launch “joyn”

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Asia-Pacific Middle Class Growth Will Drive Communications Revenue Growth

Between 2009 and 2020, the amount of consumer spending in the Asia-Pacific region will nearly have doubled, and will represent the largest single regional volume of spending, outstripping Europe, North America, Central and South America and the Middle East and Africa.

That will have important ramifications for providers of communication apps and services, creating much larger markets than ever have been seen in those regions.

That will have important ramifications for providers of communication apps and services, creating much larger markets than ever have been seen in those regions.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Saturday, December 22, 2012

36% of U.S. Households Might be "Wireless Only"

Some 35.8 percent of U.S. homes did not use or buy fixed network telephone service during the first half of 2012, an increase of 1.8 percent since the second half of 2011, according to the latest survey and report by the Centers for Disease Control.

In addition, 15.9 percent of U.S. adults received all or almost all calls on wireless phones despite also having a fixed network telephone service.

The only thing that would have been surprising about the latest survey is if the wireless substitution trend had stopped or reversed. CDC does not that the rate of substitution has slowed to 1.8 percent over the first six months of 2012.

CDC says that is the slowest rate of increase since 2008.

At current rates of change, in about a decade, about 70 percent of U.S. adults would be "wireless only."

As has been the case in earlier CDC studies, four demographic groups primarily account for the "wireless only" preferences. Younger adults aged 25 to 34, adults living only with unrelated adult roommates, adults renting their home, and adults living in poverty are those groups.

Among households with both landline and wireless telephones, 29.9 percent received all or almost all calls on the wireless telephones between January 2012 and June 2012. These wireless-mostly households make up 15.9 percent of all households, CDC says.

The shift to mobile forms of voice service also corresponds with a shift of household spending on voice, Internet access and video services. Since 2001, spending priorities have shifted to mobile, Internet and video, as fixed voice spending has dropped, according to Chetan Sharma.

Researchers at the International Telecommunications Union and Pyramid Research likewise believe the same basic trends will occur.

Over the 2000 to 2014 period, fixed voice subscriptions will decline by 50 percent, while mobile subscriptions will grow by 100 percent.

In addition, 15.9 percent of U.S. adults received all or almost all calls on wireless phones despite also having a fixed network telephone service.

The only thing that would have been surprising about the latest survey is if the wireless substitution trend had stopped or reversed. CDC does not that the rate of substitution has slowed to 1.8 percent over the first six months of 2012.

CDC says that is the slowest rate of increase since 2008.

At current rates of change, in about a decade, about 70 percent of U.S. adults would be "wireless only."

As has been the case in earlier CDC studies, four demographic groups primarily account for the "wireless only" preferences. Younger adults aged 25 to 34, adults living only with unrelated adult roommates, adults renting their home, and adults living in poverty are those groups.

Among households with both landline and wireless telephones, 29.9 percent received all or almost all calls on the wireless telephones between January 2012 and June 2012. These wireless-mostly households make up 15.9 percent of all households, CDC says.

The shift to mobile forms of voice service also corresponds with a shift of household spending on voice, Internet access and video services. Since 2001, spending priorities have shifted to mobile, Internet and video, as fixed voice spending has dropped, according to Chetan Sharma.

Researchers at the International Telecommunications Union and Pyramid Research likewise believe the same basic trends will occur.

Over the 2000 to 2014 period, fixed voice subscriptions will decline by 50 percent, while mobile subscriptions will grow by 100 percent.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Friday, December 21, 2012

"Broadband Access" is More Nuanced, These Days

Consider that, in the G-20 countries, mobile broadband went from negligible to a majority of all access connections in just five years, between 2005 and 2010, according to Business Insider.

In five more years, in 2015, mobile G-20 Internet connections will be about 80 percent of all connections, Business Insider estimates. That has some clear implications for the way we evaluate “broadband” penetration. For starters, “mobile” access might be more important, more of the time, than fixed modes.

Traditionally, the reason for buying broadband access services was for fast Internet access for some sort of PC, at a fixed location. These days, there are other reasons beyond “PC access,” and many more situations where “mobile broadband” is preferred.

Some users might want a fixed connection, solely or in part, to offload data sessions from a mobile network to a fixed network, to get access to the Internet from some other devices, such as a tablet or iPod.

Some might want broadband access to support Internet access for game playing consoles or some other video device (Roku, for example) that displays Internet video on a TV. In other words, there are many more devices, other than PCs, that derive value from a fixed network broadband connection.

Notably, a Business Insider poll suggests 45 percent of users are doing their browsing on a tablet, 24 percent on a notebook and 17 percent on desktop PCs. About 14 percent of browsing now is conducted on a smart phone.

There are other implications, such as our notions about “digital divides.” Approximately nine out of ten Hispanics have access to the Internet, when extended family, work, school, and other

public places are included, according to Nielsen.

But Hispanics are less likely to have Internet access at home compared to the U.S. average (62 percent and 76 percent, respectively). So is that a problem? Yes, but a problem that is solving itself, it appears. Over the past year (2011 to 2012), Hispanics increased home broadband use by 14 percent, which is more than double the six percent growth of broadband use in the general market.

But there are other important “demand” angles. Hispanics are three times more likely to

have Internet access using a mobile device, but not have Internet at home (nine percent

compared to three percent, respectively). In other words Hispanices, as blacks and Asians, “overindex” for mobile broadband.

Overall, Hispanics are 28 percent more likely to own a smart phone than non-Hispanic

whites.

In other words, many segments of the U.S. population, for example, prefer to buy mobile broadband than fixed broadband.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

When Cutting Price Won’t Help

It is a truism of economics that price and sales are directly and inversely related . In other words, lower the price of a product and consumers tend to buy more; raise the price and consumers buy less. In fact, the whole point of some public policy policies (taxes, rebates, subsidies, penalties, credits, tolls, fees) is to dampen demand for some products or encourage demand for some products.

Communications markets are not exempt. Raise prices and people can be expected to consume less; drop prices and people theoretically buy more. But that only works up to a point.

Demand for the product, and ability to supply it, has to exist. And that is getting to be a problem for some communications or entertainment products.

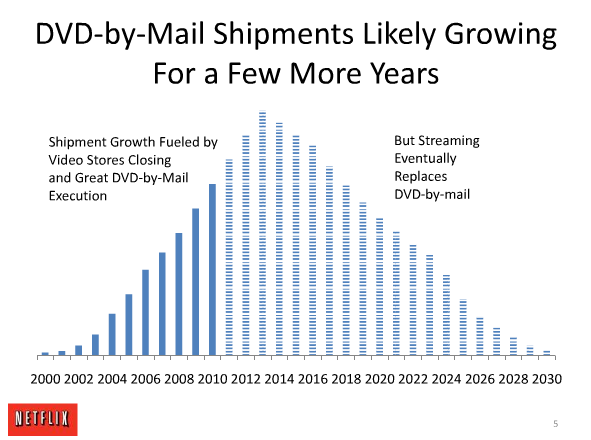

Demand for streamed versions of items in the Netflix catalog is growing; demand for disc rentals is shrinking. Presumably Netflix could drop prices for “DVD only” versions of the product. But consumer preferences are shifting, and it is not clear whether even significant price drops would reverse the streaming versus DVD by mail volume changes.

Demand for streamed versions of items in the Netflix catalog is growing; demand for disc rentals is shrinking. Presumably Netflix could drop prices for “DVD only” versions of the product. But consumer preferences are shifting, and it is not clear whether even significant price drops would reverse the streaming versus DVD by mail volume changes.

You might argue something similar is happening with mobile voice and fixed network voice, or video entertainment subscriptions.

To be sure, there’s a relatively simple reason people globally prefer to use mobile for voice. In many markets, mobile is the only way to make a call. In 2010, about 90 percent of total call volumes in Brazil, Russia and China occurred on a mobile device. That is a market where there is no functional substitute product, so fixed network voice pricing isn’t relevant.

In other markets where both mobile voice and fixed voice are available, mobile is cheaper than using fixed services. In these markets, retail pricing and packaging, not just user preferences, drive usage.

Classical economics would suggest the suppliers could increase buying and use of fixed network voice services by dropping the price. Some would argue that is precisely what Skype and cable digital voice services have done.

In the video entertainment business, the price and volume consumed trends are not so pronounced, yet. But some surveys suggest not only that the problem of actual cord cutting is growing, but that demand is the issue.

The implication is that even a price cut for video subscriptions might not work to stimulate demand, on the part of some growing percentage of consumers.

About 33 percent of people who have “cut the cord” on their video entertainment subscriptions would not buy again, even if prices were cut in half, a study by TechBargains.com has found.

That opinion illustrates the level of growing dissatisfaction with video entertainment services sold by cable, satellite and telco TV providers, at least in some consumer segments.

Despite the fact that 83 percent of surveyed cord cutters abandoned their video entertainment services because of the “high cost,” even a price cut in half would not be enough to entice many cord cutters to buy again.

Significantly, the study also suggests that video entertainment services are not even viewed as providing the best quality and variety of programming by 17 percent of people who disconnected their cable TV or satellite TV services. For an industry that claims to provide the best quality and variety, that is a problem.

Another possibly-significant finding is that consumers who abandoned their fixed network phone service were two times more likely to eliminate their cable TV or satellite TV subscription than those who have not disconnected their home telephone.

Of respondents who have gotten rid of their landline, 36 percent also discontinued their cable TV or satellite TV service. Of respondents who still have their landlines, 19 percent have cut the cable cord.

The survey found that 60 percent of respondents no longer have a landline telephone service, either.

Although the survey also found that 57 percent of people that still have a landline voice service do not plan to disconnect their landline in the next year, that statistic might be only mildly reassuring, since it suggests that 43 percent might cut the cord on their fixed network voice service within a year or two.

The Federal Communications Commission Technology Advisory Council has estimated that U.S. time division multiplex fixed consumer access lines could dip to perhaps 20 million units by about 2018.

Others, such as Kent Larsen, CHR Solutions SVP, think lines overall could dip to about 50 million over the next five years, then to about 40 million on a long term and somewhat stable basis.

Keep in mind that the U.S. market supported about 150 million voice lines in service around the turn of the century. One might argue, under such circumstances, that even lower prices would not entice many consumers to buy fixed network voice again.

Communications markets are not exempt. Raise prices and people can be expected to consume less; drop prices and people theoretically buy more. But that only works up to a point.

Demand for the product, and ability to supply it, has to exist. And that is getting to be a problem for some communications or entertainment products.

You might argue something similar is happening with mobile voice and fixed network voice, or video entertainment subscriptions.

To be sure, there’s a relatively simple reason people globally prefer to use mobile for voice. In many markets, mobile is the only way to make a call. In 2010, about 90 percent of total call volumes in Brazil, Russia and China occurred on a mobile device. That is a market where there is no functional substitute product, so fixed network voice pricing isn’t relevant.

In other markets where both mobile voice and fixed voice are available, mobile is cheaper than using fixed services. In these markets, retail pricing and packaging, not just user preferences, drive usage.

Classical economics would suggest the suppliers could increase buying and use of fixed network voice services by dropping the price. Some would argue that is precisely what Skype and cable digital voice services have done.

In the video entertainment business, the price and volume consumed trends are not so pronounced, yet. But some surveys suggest not only that the problem of actual cord cutting is growing, but that demand is the issue.

The implication is that even a price cut for video subscriptions might not work to stimulate demand, on the part of some growing percentage of consumers.

About 33 percent of people who have “cut the cord” on their video entertainment subscriptions would not buy again, even if prices were cut in half, a study by TechBargains.com has found.

That opinion illustrates the level of growing dissatisfaction with video entertainment services sold by cable, satellite and telco TV providers, at least in some consumer segments.

Despite the fact that 83 percent of surveyed cord cutters abandoned their video entertainment services because of the “high cost,” even a price cut in half would not be enough to entice many cord cutters to buy again.

Significantly, the study also suggests that video entertainment services are not even viewed as providing the best quality and variety of programming by 17 percent of people who disconnected their cable TV or satellite TV services. For an industry that claims to provide the best quality and variety, that is a problem.

Another possibly-significant finding is that consumers who abandoned their fixed network phone service were two times more likely to eliminate their cable TV or satellite TV subscription than those who have not disconnected their home telephone.

Of respondents who have gotten rid of their landline, 36 percent also discontinued their cable TV or satellite TV service. Of respondents who still have their landlines, 19 percent have cut the cable cord.

The survey found that 60 percent of respondents no longer have a landline telephone service, either.

Although the survey also found that 57 percent of people that still have a landline voice service do not plan to disconnect their landline in the next year, that statistic might be only mildly reassuring, since it suggests that 43 percent might cut the cord on their fixed network voice service within a year or two.

The Federal Communications Commission Technology Advisory Council has estimated that U.S. time division multiplex fixed consumer access lines could dip to perhaps 20 million units by about 2018.

Others, such as Kent Larsen, CHR Solutions SVP, think lines overall could dip to about 50 million over the next five years, then to about 40 million on a long term and somewhat stable basis.

Keep in mind that the U.S. market supported about 150 million voice lines in service around the turn of the century. One might argue, under such circumstances, that even lower prices would not entice many consumers to buy fixed network voice again.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

What Does Dish Actually Want from LTE?

Lots of investors operate on the premise that spectrum has value, even if the owner doesn't really want to be in the service provider business. In fact, some would argue, with good reason, that entrepreneurs such as Craig McCaw always have operated on the theory that it always is good to acquire spectrum, as it is good to acquire land, irrespective of the immediate ability to build an operating business using such spectrum.

If fact, much spectrum originally licensed to support non-profit educational purposes (Multichannel Multipoint Distribution Service, for example) has been redeployed to support mobile communications. Leading U.S. cable operators also have invested in mobile spectrum ownership over the past couple of decades, eventually selling that spectrum rather than building operating businesses.

For that reason, many observers have insisted that Dish Network's actual objective is to sell its now more-valuable spectrum to another service provider, rather than building and operating its own mobile network.

According to that view, Dish Network will do enough to deploy an AWS-4 network, at minimum cost, to meet the FCC’s construction criteria, to persuade a potential buyer such as AT&T to purchase either Dish Network in total or at least the 4G spectrum assets.

Others argue that Dish really is serious about getting into the high-speed access business, and therefore does need to create a 4G network.

Still, there has been an argument argument for decades that, sooner or later, both Dish Network and DirecTV would be acquired by AT&T and Verizon, both to bolster video entertainment business market share.

If so, then the mobile spectrum would simply be added value for the buyer.

If fact, much spectrum originally licensed to support non-profit educational purposes (Multichannel Multipoint Distribution Service, for example) has been redeployed to support mobile communications. Leading U.S. cable operators also have invested in mobile spectrum ownership over the past couple of decades, eventually selling that spectrum rather than building operating businesses.

For that reason, many observers have insisted that Dish Network's actual objective is to sell its now more-valuable spectrum to another service provider, rather than building and operating its own mobile network.

According to that view, Dish Network will do enough to deploy an AWS-4 network, at minimum cost, to meet the FCC’s construction criteria, to persuade a potential buyer such as AT&T to purchase either Dish Network in total or at least the 4G spectrum assets.

Others argue that Dish really is serious about getting into the high-speed access business, and therefore does need to create a 4G network.

Still, there has been an argument argument for decades that, sooner or later, both Dish Network and DirecTV would be acquired by AT&T and Verizon, both to bolster video entertainment business market share.

If so, then the mobile spectrum would simply be added value for the buyer.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Will UK 4G Auction Change Market Structure?

There often is hope that major spectrum auctions will increase the amount of competition in a market, sometimes by enticing and enabling new entrants to enter a market. Regulators often specify that some blocks of spectrum are reserved for such new entrants, for example.

The upcoming U.K. 4G spectrum auctions are likely to see "new" bidders, but the actual amount of impact on the mobile market is likely to be rather insignificant, some would argue. Already, three new names have surfaced as bidders, including BT, which has been barred from the mobile business by regulator action.

Everything Everywhere; HKT Company, a subsidiary of Hong Kong operator PCCW; Three owner Hutchison 3G; MLL Telecom; Niche Spectrum Ventures (BT Group); O2's parent firm Telefónica UK and Vodafone are the seven bidders that have paid the entry fee for the auction.

That naturally raises speculation about whether BT might try and get back into the mobile business as a facilities-based provider, where it today operates as a virtual mobile network operator.

That appears to be unlikely, as BT is probably more interested in using spectrum to reach households it cannot get to using its fixed network.

So some might argue the auctions have little chance of upsetting the current market structure in the United Kingdom. Wireless Intelligence predicts that, by 2014, the same four leaders of the 3G market also will top the 4G market.

The upcoming U.K. 4G spectrum auctions are likely to see "new" bidders, but the actual amount of impact on the mobile market is likely to be rather insignificant, some would argue. Already, three new names have surfaced as bidders, including BT, which has been barred from the mobile business by regulator action.

Everything Everywhere; HKT Company, a subsidiary of Hong Kong operator PCCW; Three owner Hutchison 3G; MLL Telecom; Niche Spectrum Ventures (BT Group); O2's parent firm Telefónica UK and Vodafone are the seven bidders that have paid the entry fee for the auction.

That naturally raises speculation about whether BT might try and get back into the mobile business as a facilities-based provider, where it today operates as a virtual mobile network operator.

That appears to be unlikely, as BT is probably more interested in using spectrum to reach households it cannot get to using its fixed network.

So some might argue the auctions have little chance of upsetting the current market structure in the United Kingdom. Wireless Intelligence predicts that, by 2014, the same four leaders of the 3G market also will top the 4G market.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

The Roots of our Discontent

Political disagreements these days seem particularly intractable for all sorts of reasons, but among them are radically conflicting ideas ab...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...