Will over the top messaging, or video entertainment, will be a more important revenue source for mobile service providers? And, to the extent revenue is earned, will it be a direct or indirect contributor?

Your answer likely would be different, based on which market is considered. Countries at immediate risk include the Netherlands, South Korea, Japan, Spain, Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Russia.

At moderate risk are Canada, the United States, Italy, Poland, Australia, Austria, France, and Hungary, according to analysts at McKinsey.

At low risk are most countries, where voice and text messaging remain staples, and where mobile data access adoption remains low, at least for the moment.

Conversely, markets where consumers have eagerly embraced social messaging, where smartphone adoption is high or text messaging tariffs are moderately high are most exposed.

Informa Telecoms & Media has predicted that mobile operators will generate a total of $722.7 billion in revenues from text messaging revenues between 2011 and 2016.

Third-party providers of over the top (OTT) messaging services will earn about $8.7 billion in 2016. That disparity in revenue illustrates the issue. Mobile service providers will lose about two orders of magnitude more revenue than all OTT apps earn.

So even if telcos become significant providers of OTT messaging, and it is not clear that can be done to any significant degree, you might ask whether the effort is better placed elsewhere.

Put another way, if the potential market is 50 cents a month in revenue, while the lost text messaging revenue represents $10 a month, it isn’t immediately clear whether the effort is justified.

Some will argue that new forms of bundled products (carrier OTT plus other carrier products) will prove viable. That assumes the carrier OTT product has enough intrinsic value to warrant buying it.

A carrier can, of course, simply structure tariffs in a way that makes carrier voice, text messaging and carrier OTT messaging a single retail offer. Even then, one might argue the effort (time, people and capital) might offer more substantial revenue impact if deployed in other areas.

Still, some might argue the upside is in “higher perceived value” for the carrier communications package, not direct revenue. That’s a valid strategy, so long as carrier OTT messaging actually gets any sizable traction with customers.

At least for the moment, indirect revenue sources seem the most likely outcome, and perhaps most significant for video entertainment, rather than messaging, even if that appears to be off in the future.

Consider that telcos today earn far more revenue from video entertainment than VoIP. In fact, any gains in telco VoIP are more than matched by losses in the traditional voice business. In fact, over the top messaging and voice alternatives almost certainly will be the main trend, not the earning of incremental revenues from carrier VoIP or over the top messaging.

The magnitude of losses from legacy products will simply be too massive, in some markets, with losses possibly ranging from 20 percent to 30 percent over several years, in both voice and text messaging services. It is very hard to see how carrier over the top messaging compensates for losses on that scale.

People will buy mobile Internet access so they can use the over the top messaging apps, as well as buying larger buckets of usage to watch mobile video. In both cases, the primary revenue upside is indirect, coming in the form of higher end user spending on access packages.

Perhaps the bigger question is whether video entertainment--provided as a service or through a gateway app--could emerge as a significant direct revenue generator, and not simply an application that drives demand for Internet bandwidth.

Much depends on the answer.

Though helpful for mobile service providers, direct video entertainment services, modeled on the subscription video model, such a development could have major ramifications for existing providers of such services, including cable TV, satellite TV and telco TV providers, shifting demand in possibly significant ways.

Does mobile-delivered video entertainment seem likely to replicate traditional linear TV? Most probably would agree that is rather unlikely, simply because point-to-multipoint networks are efficient ways to deliver linear content, while point-to-point communications networks, especially mobile networks, are not efficient.

But future video entertainment might include at least some forms that are passably well suited for delivery even over point-to-point networks. Obviously, recent end user behavior with respect to consumption of YouTube, Netflix streaming and other forms of non-linear video consumption provide a reason for suggesting that sort of behavior could underpin a newer form of video service not dependent on linear delivery (not pushed or broadcast but pulled by viewers).

So it is at least possible that some demand for traditional TV subscriptions could shift to mobile delivery, as a byproduct of a switch to greater reliance on "pull" or content on demand modes.

It wouldn't be easy, but video entertainment remains one of the more reliable applications a service provider can sell.

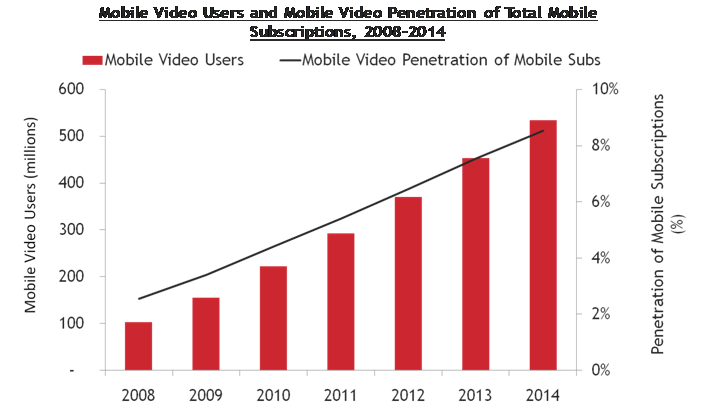

The number of users globally paying for mobile video and TV services is expected to jump to 534 million by 2014, a five-fold increase from 2008, says Pyramid Research.

Derek Medlin, senior analyst at Pyramid Research, says "this is equivalent to 8.5 percent of all mobile subscriptions, up from the current 2.5 percent level."

"Looking ahead, Asia/Pacific will remain in the top spot, attaining more than 281 million subscriptions by 2014, although we expect Latin America to grow at the fastest pace, increasing at a CAGR of 39 percent from 2009 to 2014," Medlin says.

Until now, mobile operators haven’t done much to promote mobile video. In fact, under challenged bandwidth circumstances, it sometimes makes sense to actively discourage such consumption.

But Long Term Evolution helps. And broadcast forms of LTE will help more, at least for linear content delivery. The challenges of delivering mobile content are balanced by the size of the revenue opportunity, though.

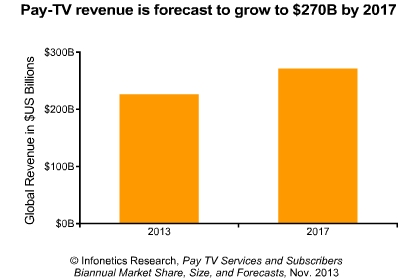

Worldwide video service revenue (cable TV, satellite TV and telco TV) grew in the first half of 2013 to $110 billion, up two percent over the second half of 2012, despite weakness in the U.S. market, where video subscribers are declining at a pace of 1.5 percent to 2.5 percent annually.

You can make your own determinations about whether that trend indicates non-interest in the product, or simply non-interest in the way retail offers are constructed.

You can make your own determinations about whether that trend indicates non-interest in the product, or simply non-interest in the way retail offers are constructed.

By 2017, Infonetics expects the global video subscription services TV market to hit $270 billion in revenue, a 2012–2017 compound annual growth rate of nearly five percent.

The issue is how service providers can earn revenue from mobile video, which today is largely a potential revenue stream for application providers.

Although only a third of Verizon subscribers are on LTE, those users consume 64 percent of its data, with a “surprising” amount of that being video content, according to Verizon.

And that's why entertainment video might someday generate far more revenue for mobile service providers than over the top messaging.

And that's why entertainment video might someday generate far more revenue for mobile service providers than over the top messaging.