AT&T will announce its purchase of DirecTV as early as May 18, 2014. The deal, which some believe will cost AT&T about $50 billion, is controversial in some quarters.

The contrarian view is that the deal exposes AT&T to a greater dividend payment burden, increases debt load and offers rather negligible strategic advantages, as the linear video business is declining or, at best, flat, in terms of revenue.

The opposing view is that the deal makes AT&T a leading player in linear video entertainment for the first time, vaulting AT&T to about second in terms of overall video market share, providing lots of additional cash flow.

Even if the deal does not directly improve AT&T's ability to upgrade its Internet access speeds, the additional cash will underpin the effort.

Also, the deal might allow AT&T to free up more bandwidth on its fixed network for Internet access services, at least in region, where AT&T already operates fixed networks. At some incremental level, the deal also gives AT&T enough new heft in contract negotiations with content providers that the cost of acquiring content will drop.

Also, the same deal should increase AT&T's leverage in negotiating for future rights to streamed versions of linear content.

Saturday, May 17, 2014

AT&T Will Announce DirecTV Acquisition May 18, 2014

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Friday, May 16, 2014

What is Next Step in French Mobile Market Consolidation?

In the wake of the Numericable acquisition of SFR, which made France’s biggest cable TV operator the second-largest mobile service provider in France, market leader Orange apparently is in talks about an acquisition of Bouygues Telecom, though much speculation suggests it is Bouygues that will buy Illiad’s Free Mobile.

Holding 40 percent market share, it might have been unthinkable some time ago that Orange would be allowed to get bigger in the French market, and that might yet remain the case. Numericable now has about 30 percent share of the French mobile market.

Bouygues has about 18 percent market share, while Illiad’s Free Mobile has about 10 percent share. Under past conditions, it would have been unthinkable for regulators to consider supporting any mergers that would make Orange bigger.

And, most likely, that remains the case, even as French communications regulators actively seek a reduction of French mobile carriers from four to three leading suppliers.

Instead, regulators are likely to favor a combination of Bouygues and Free Mobile, a move that would create a new competitor with about 28 percent market share.

An Orange bid to buy Bouygues would trigger antitrust review and an uphill battle. So one line of thinking is that such a deal is largely tactical, aimed at driving up the price Illiad might have to pay to acquire Bouygues.

It might seem a bit unusual that the smaller firm is seen as buying the larger firm, but each firm’s equity value matters. Illiad is valued more richly than Bouygues, for example. Also, Bouygues telecom operations represent about a third of total Bouygues revenues.

For Illiad, communications is its only business.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Who Wins, Who Loses, Always Matters for Communications Policy

Perhaps significantly, there seems to be a growing belief within the European Union communications community--including some regulators--that a new balance between policies fostering “competition” at the expense of “market power” must be struck.

For the most part, such discussions center on the need for greater scale in the European Union communications industry.

But European Commission regulatory authorities and member national governments do not appear to agree on how to create a more-unified communications market for the European Union.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, for example, has called for a reform to EU competition law in the telecom sector, allowing the formation of bigger pan-European service providers, even when that reduces competition.

"A balance needs to be achieved between market power and competition so that we can score internationally," Merkel said. Jean-Claude Juncker, a candidate for European Commission president, has also recently added his voice to the growing political support for cross-border mergers of telecom groups.

EC competition authorities, including Joaquin Almunia, European Commission vice president for competition policy, oppose easing merger restrictions.

In large part, the differences of opinion reflect national thinking, as opposed to “European” thinking, Almunia seems to suggest. But the differences also reflect traditional "bureaucratic" squabbles over where power and authority resides.

Almunia notes that national regulators are unwilling to cede authority in key areas such as spectrum allocation, in large part because auctions of such spectrum are significant generators of governmental revenue.

“These governments don't want to allocate spectrum at EU level because they are not willing to forgo the billions raised in auctions, which go directly to their respective national coffers,” Almunia said. “Unfortunately, they prefer to keep spectrum allocation and regulatory decisions in their national hands.”

At some level, the differences also reflect bureaucratic (“bureaucratic” in the analytical sense, not the derogatory sense) dynamics.

It never would be out of place or unusual for a higher authority to argue it is better placed to conduct regulatory operations than lower authorities (again, in the sense of geographic scope, not relevance or value).

Rarely do regulators or officials at any level, in any domain, voluntarily argue their mission is finished and that the agency should be abolished.

Still, those issues aside, there are now new arguments about the objectives of communications policy within the European Union. Traditionally most concerned with fostering competition, at least some regulators now say that cannot be the exclusive or primary focus, given the need for massive investments in next generation infrastructure.

Also, even the proponents of consolidation have nuanced views. National governments often oppose takeovers of major domestic companies or industries, even as they support their own national firms being the buyers of companies in other nations that would increase communications service provider scale.

Almunia, Merkel and Juncker all seem to agree that one key difference between communications markets in the EC and the United States and China, for example, is sheer scale.

But Almunia and Merkel differ on the amount of consolidation that should be encouraged. They also disagree about a transfer of decision-making authority. Almunia bluntly argues that what is required is a “fully-fledged EU telecom regulator, EU-wide spectrum allocation, and no roaming charges.”

Perhaps more significantly, Almunia also argues that competition rules that would speed up market consolidation are unnecessary.

“As to competition rules, they would not have to change for enforcement to adapt to this scenario,” Almunia said. “In an integrated EU market, the definition of relevant markets would automatically change,” with mergers considered on their pan-EU impact, not national impact.

“Therefore, if our political leaders want to be rigorous when they talk about the telecom industry in the EU, they should start thinking as European leaders, rather than giving precedence to their respective national priorities,” Almunia said.

Ironically, all parties seem to want a single EU telecommunications market. But what that means, who benefits and who might lose, is the issue.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Will U.S. Regulators Reach Same Conclusions as French Regulators?

Will U.S. regulatory officials take the same view as do French regulators about how best to sustain and promote competition in the U.S. mobile business? Perhaps they will.

Though European Union regulators still tend to prefer four mobile service providers in each market, rather than allowing consolidation to three, French regulators are concerned that long-term stable mobile markets in France require consolidation.

As with policies that must balance investment with competition, there is an inherent tension between regulatory policies that promote maximum feasible competition and yet also promote maximum feasible investment in next generation networks.

The French government now has concluded that ruinous levels of competition exist, and that stable competition, long term, will be served if the mobile market consolidates to three dominant national providers.

In the U.S. market, at least so far, Federal Communications Commission regulators and antitrust authorities have signaled a belief that maintaining four national competitors is necessary.

But there are at least some hints that at least one FCC commissioner now is beginning to agree with French regulators.

Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel reportedly has acknowledged privately that Sprint and T-Mobile US may not remain viable as independent companies. That is the same view now expressed in public by French national regulators as well.

The problem in many fixed network markets is that there is only one ubiquitous fixed network.

So regulators essentially have had to rely on wholesale mechanisms to support competition.

Ironically, such moves also tend to depress facilities investment. The issue in mobile markets is less that of limited facilities, but the ability to sustain long term operations.

And some argue the current structure of four leading U.S. providers cannot last, based on disproportionate differences in revenue, profit and ability to continue investing in next generation networks.

“We believe Sprint and T-Mobile’s lack of capital investment in network infrastructure and spectrum over the past five years were the primary reasons for AT&T and Verizon’s market share gains during that period,” say analysts at BTIG Research.

Likewise, an analysis by New Street Research makes the same point. "Our analysis shows that neither Sprint nor TMUS have enough revenue to cover their fixed costs and it is highly unlikely that both will capture enough new revenue to do so," New Street Research analysts say. “There simply isn't enough revenue in the industry for four carriers to cover their fixed costs unless there is a significant shift in market share."

The analysts also say it is possible that a reduction in U.S. mobile service providers still could provide consumer benefits. In three markets--Netherlands, Greece, and Austria--the number of nationwide competitors dropped from four to three and average pricing in the markets declined 15 percent to 40 percent after the consolidation.

"If the companies merge now, while they are in relatively good shape, the merger will result in lower costs in the context of an improving business, which our data suggests should lead to investment and lower prices," New Street Research believes. On the other hand, "If the companies are only permitted to merge when one has faltered or failed, the combined company will be less well-positioned to compete against the two well-funded incumbents."

Perhaps U.S. regulators ultimately will reach the same conclusions as have French regulators.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

New FCC Rules Help Independent Sprint and T-Mobile US, But Promise More Scrutiny of Any Sprint Effort to Acquire T-Mobile US

New rules adopted by the Federal Communications Commission are going to help Sprint and T-Mobile US in upcoming auctions of 600-MHz spectrum, but also will make it more difficult for Sprint to acquire T-Mobile US.

At its May 15, 2014 meeting, the FCC voted to restrict the amount of spectrum Verizon Communications and AT&T will be able to buy in the 2015 auction of spectrum in the 600-MHz band that formerly was used for TV broadcasting.

Assuming 85 MHz to 100 MHz eventually is freed up for reallocation, no more than 30 MHz might be reserved for smaller bidders, including Sprint and T-Mobile US.

On the other hand, the Commission also adopted rules that will make it harder for Sprint to acquire T-Mobile US.

The Commission changed its “spectrum screen” rules used to evaluate mergers and acquisitions in the U.S. mobile business, with the biggest impact on Sprint.

The FCC has indicated it will add about 101 megahertz of Clearwire spectrum to Sprint’s total spectrum holdings, for purposes of determining Sprint’s spectrum position in specific markets.

In some cases, that will trigger a review in which higher acquisition or merger scrutiny occurs, because Sprint will have 33 percent or more of the available mobile broadband spectrum in some markets.

On the other hand, the Commission also now makes a distinction between “lower band” (below 1 GHZ) spectrum and “higher band” spectrum (above 1 GHZ) ownership when evaluating potential mobile mergers or acquisitions.

Potential deals by firms with more than a third of total spectrum in the lower bands (AT&T and Verizon, primarily) will face higher merger or acquisition scrutiny.

But Sprint and T-Mobile US, after the 600-MHz auctions, might also find themselves with combined lower-frequency holdings that trigger more scrutiny, in some markets.

On the other hand, in the future, if Dish Network were to try to acquire T-Mobile US, Dish would likely benefit, since Dish owns no spectrum in the lower frequencies, and even with T-Mobile US assets would be unlikely to trigger the more-intense regulatory review.

The spectrum screen is the way the Federal Communications Commission accounts for existing spectrum market share when creating bidding rules. Up to this point, much former Clearwire spectrum has not been counted against Sprint’s total spectrum holdings.

The new screen would mean Sprint exceeds a threshold of about a third of all spectrum in specific markets. That means Sprint would face new and higher scrutiny if it were to try and acquire T-Mobile US, especially after a successful 600-MHz auction.

“If a proposed transaction would result in a wireless provider holding approximately one third or more of available spectrum licenses in a given market, that transaction will continue to trigger a more detailed, case-by-case competitive analysis by the Commission,” the FCC said.

That rule change does not affect Sprint’s ability to bid on the set-aside 600-MHz spectrum, though.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

AT&T Bid for DirecTV Really Isn't Puzzling

AT&T’s potential deal to acquire DirecTV will strike many as puzzling, given the deal’s inability to directly affect either AT&T’s mobile business, its international profile or fixed network business.

To some extent, the potential bid has been triggered by the Comcast bid to buy Time Warner Cable, a deal that would vault Comcast clearly into leadership of the U.S. high speed access business, though keeping its overall video subscriber market share below a 30-percent level that draws regulatory scrutiny.

When a key competitor in a supplier’s core market makes a move that promises to make it stronger and bigger, rivals typically have to respond.

To be sure, AT&T might well have preferred an opportunity to expand internationally. But deals large enough to make a difference, available at reasonable cost and relatively likely to win regulatory approval arguably did not exist.

| source: National Broadband Plan |

And a new threat in its core market likely also affected strategic thinking. As difficult as “broadband” and “video” have been for U.S. telcos, in terms of capital investment intensity and financial return, it now is clear that the future of fixed networks is bound with high speed access and video entertainment.

And in that sense, AT&T has to take seriously a jump in market share for high speed access, by Comcast, to 40 percent of the U.S. market, making Comcast the undisputed market leader.

That has strategic implications for all other major competing service providers.

To the extent that fixed networks have a clear value and rationale, it is as suppliers of the highest-bandwidth platform, delivering connectivity at the lowest cost of any platform, on a cost-per-bit basis.

| Source: UBS |

In that regard, it is high speed access itself which becomes the foundation service, but video entertainment has emerged as the lead application for such a network, beyond Internet access.

Perhaps not far behind is the value of the fixed network as a means for offloading traffic from a mobile network, the most-important indirect driver of value for the fixed network.

So it is not so much Comcast’s gain in video subscriber share that are most important, from AT&T’s perspective. It is the immediate market share lead in high speed access which is most important.

What is very clear is that, with a few exceptions (Verizon FiOS and Google Fiber, plus a few independent ISPs), cable-provided high speed access operates faster than telco high speed access. Cable TV suppliers also are winning the battle in terms of net new high speed additions as well.

Some might argue that acquiring DirecTV does very little to help AT&T extend its potential high speed access footprint. That is true.

But there are other important elements. DirecTV would supply high-margin revenue and cash flow that AT&T can use to upgrade its fixed networks for faster speeds and video services.

And there are few acquisitions AT&T actually can make in the U.S. market in its core triple play and quadruple play markets. Regulators already rejected AT&T’s effort to buy T-Mobile US, as that was deemed to reduce mobile competition too much.

And AT&T has, since 2006, not been in the market to expand its overall fixed network footprint for several reasons. Higher returns from mobile services are a primary reason. But market share issues exist.

| source: http://www.leichtmanresearch.com/press/031714release.html |

AT&T’s fixed network market share (looking only at the telephone industry), measuring either by subscribers or revenue, is the highest of any telco, reaching more than 40 percent share of voice or high speed access connections.

AT&T’s fixed network passes about 50 million U.S. homes, or about 42 percent of total U.S. homes.

AT&T holds about 47 percent of “telco” high speed market share, for example, though only about 20 percent of total U.S. ISP high speed access accounts.

The point is that, within the U.S. telephone industry, AT&T already arguably has reached a size where any further acquisitions would be challenged on competitive grounds.

| http://www.tefficient.com/Blog-State-of-industry/ |

The upshot is that AT&T cannot easily make domestic acquisitions in the fixed network or mobile realms. Buying DirecTV, though, changes only AT&T’s small video service market share.

In 2013, for example, AT&T had only about six percent share of the linear video subscription business. DirecTV had about 21 percent share. So a combined entity would have only about 27 percent market share.

The point is that AT&T would face far fewer regulatory opposition by making a DirecTV acquisition, and almost no chance of approval were AT&T to propose buying additional mobile or fixed network market share.

The other issue is that AT&T (originally SBC) has grown primarily through acquisition, not organic growth.

AT&T bought Pacific Telesis for $16.6 billion in 1997, Ameritech for $73.2 billion in 1999, AT&T for $16.1 billion in 2005 and BellSouth for $85.2 billion in 2006. Those deals primarily gres its fixed network business.

AT&T Mobility similarly was built on acquisitions. In 2000 BellSouth Mobility and SBC merged to form Cingular. In 2004 AT&T Wireless was bought. IN 2006 AT&T Mobility acquired the former BellSouth interest in Cingular.

AT&T Mobility also acquired Dobson in 2008 and and Centennial in 2009, as well as Leap in 2014, with the failed bid for T-Mobile US in 2011.

A DirecTV acquisition is one of the few deals of any magnitude that AT&T can make, with hopes of winning approval.

The bid might seem puzzling. It really isn’t.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Driver Licenses are Key Feature Consumers Desire for Mobile Wallets

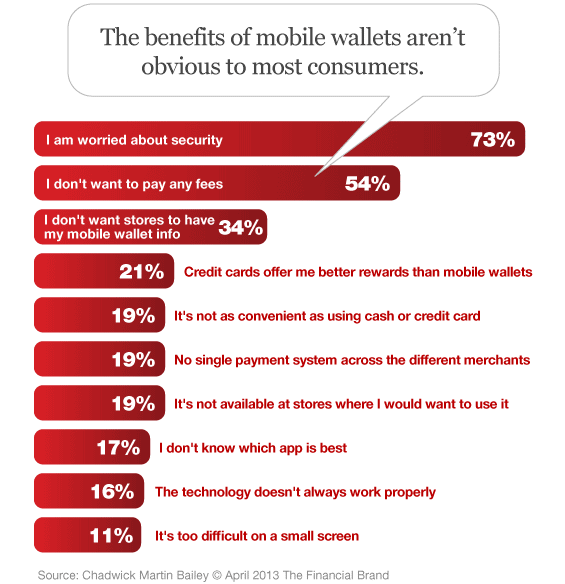

It is hard to say whether lack of familiarity, convenience. security, habits, cost or other “perceived value” issues are the key barriers to wider use of mobile wallets by consumers.

It might be simple enough to argue that consumers still do not understand what a mobile wallet is. Even for consumers who understand the concept, the practical use of a mobile wallet might yet represent major inconvenience, given the fragmentation of suppliers and retail partners that means no consumers can be sure where they can use their mobile wallets.

All that was to be expected. Products such as tablets can reach significant penetration rather quickly because the rest of the infrastructure, including widespread Wi-Fi, apps, end user behavior, business models, quality broadband (at least for purposes of supporting video apps, a key tablet app) and even familiarity with the touch interface are established.

Looking only at near field communications, most of the infrastructure has to be created, from handsets to apps to networks to retailer adoption and terminal upgrades or replacement. Other ways of handling communications between mobile payment apps and devices with retailer terminals can be used.

But illustrates the fragmentation problem. Not only are there numerous suppliers, but rival technology approaches and retailer networks are at an early stage.

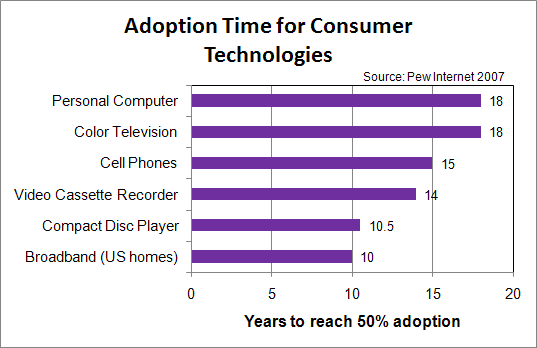

For that reason, it might take as much as a decade or more before there is significant penetration, even after consumers start to see real value. That pattern is not unusual.

Even a decade after banks introduced the capability, only about 30 percent of bank customers 65 or older used automated teller machine cards, even if 70 percent of users younger than that adopted the habit of using ATM cards.

To be sure, though some studies suggest that at least half of smartphone owners are familiar with the concept of mobile wallets, it is possible awareness is less than that. Also, in addition to fragmentation and therefore inconvenience, the value proposition is therefore limited.

For example, some argue that consumers want more than just the ability to pay for things using their mobile wallets.

Of 500 consumers surveyed in a TSYS mobile wallet survey, the top three ranking contents of today’s physical wallet were the driver’s license, payments cards, and insurance cards, in that order.

Of those surveyed by TSYS, 55 percent said they would like their driver’s license available as part of their mobile wallet service. Obviously, there are institutional barriers to that one particular desire.

So in order to fully make the switch and ditch the physical wallet, these essential components need to be added to the mobile wallet. In fact, 47 percent of consumers surveyed said that they would use mobile wallets more if they contained everything in their physical wallet.

The point is simply that mobile wallets are going to take some time to reach mass adoption levels.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Gary Kim was cited as a global "Power Mobile Influencer" by Forbes, ranked second in the world for coverage of the mobile business, and as a "top 10" telecom analyst. He is a member of Mensa, the international organization for people with IQs in the top two percent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

On the Use and Misuse of Principles, Theorems and Concepts

When financial commentators compile lists of "potential black swans," they misunderstand the concept. As explained by Taleb Nasim ...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...