As a long term matter, it has seemed logical that tier one telcos globally would begin to shift revenue focus from the consumer to the business segment, especially where competition in the fixed network segment was particularly robust.

As a long term matter, it has seemed logical that tier one telcos globally would begin to shift revenue focus from the consumer to the business segment, especially where competition in the fixed network segment was particularly robust.

That trend seems to be emerging clearly for AT&T.

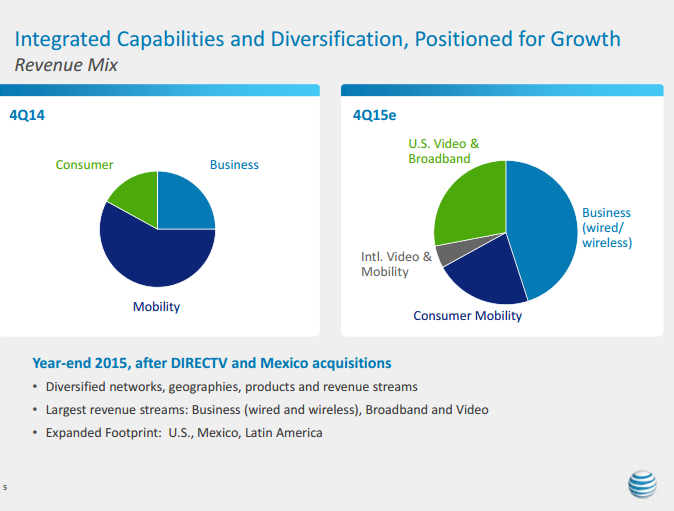

Our transactions with DIRECTV and Mexican wireless companies Iusacell and Nextel Mexico will make us a very different company, said AT&T CEO, Randall Stephenson. “After we close DIRECTV, our largest revenue stream will come from business-related accounts , followed by U.S. TV and broadband, U.S. consumer mobility and then international mobility and TV.”

Consider the magnitude of the changes. In 2014, AT&T reported earning nearly 60 percent of total revenue from mobile services. AT&T meanwhile earned about a quarter of its revenue from business customers.

Consumer landline revenue was less than 20 percent of total.

Assuming AT&T’s acquisitions of Iusacell, Nextel Mexico and DirecTV are approved, AT&T will earn about 45 percent of total revenue from business customers and about 20 percent from consumer mobility services.

About 30 percent of revenue would be earned from U.S. consumer high speed access and video entertainment.

For perhaps the first time, AT&T revenue would be driven by business accounts, not consumer services.

For the first time, AT&T would emerge as a leader in the subscription video market.

Contributions from the mobility segment would not wane, but AT&T would be far less exposed to competition in the consumer mobile segment.

All of that has key implications. AT&T will reduce reliance on U.S. market revenues and consumer “communications” revenues, to a significant extent, with a bigger reliance on video entertainment.

One might argue that diversification lessens the threat AT&T faces from cable TV, T-Mobile US and Sprint, CLECs, Google Fiber and other emerging independent ISPs.

One obvious question is what Verizon might do. So far, it has made a different bet, banking heavily on the U.S. mobile market for growth. Whether that will remain the case over the next decade is the issue. Some might argue the fundamental strategy will have to change.

The extent to which the pattern emerges elsewhere around the globe is the larger issue. Some might argue the pressure to focus on business accounts is less, since “cable TV” tends not to be a rival industry but a platform owned by tier one telcos, where it is a factor in the markets.

Also, few markets have the degree of facilities-based competition on the U.S. model.

Still, there are any number of reasons why tier one service providers ultimately might want to shift attention to business accounts. Larger revenue per account is one good reason.

Also, higher profit margins are another advantage. That is one reason why U.S. competitive local exchange carriers generally focus on business accounts only when they move out of market and compete with other telcos.

Also, to some extent, there is less competition in the business segment, compared to the consumer segment. Few competitors can compete with tier one telcos, other than other tier one telcos, in the international communications segment, or even in national large enterprise account markets.

There arguably is more competition in the mid-market segment, but growing competition in the small business (mass markets) end of the market, especially as both cable TV companies and CLECs compete in the small business market.

In consumer markets, there is fierce competition from satellite and cable TV providers. In fact, in the U.S. market, it increasingly looks as though cable TV companies are emerging as the leading providers of fixed network triple play services, not telcos.

Even in the mobile services segment, long dominated by telcos, heightened competition is occurring, putting pressure on gross revenue and profit margins. And more competition is expected,