Deutsche Telekom has launched StreamOn, a new unlimited usage plan for its German customers, who now will be able to watch video and listen to music without incurring mobile data usage charges.

Almost certainly inspired by the success of the U.S. unit’s experience with such plans, DT has signed up Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Sky, YouTube and Deutsche Telekom's own Entertain TV offering as partners.

As seems always to be the case when technology disrupts the boundaries between formerly-discrete industries (TV and radio broadcasting, cable TV, telecom, print, social networks, shopping), old regulatory concepts become unwieldy and nonsensical, as firms selling the same services labor under different regulations.

Cable TV firms, for example, are regulated differently from telcos; VoIP often is regulated differently from carrier voice; over-the-top streaming video is handled differently than broadcast media or print.

More significantly, over the long term, is that business models and consumer expectations of each product do not change, simply because the delivery method changes.

Consumers do not expect to pay for bandwidth--which is an essential requirement for broadcast TV, broadcast radio, or any network-delivered video or audio service--when consuming traditional media.

As traditional “television” and “movie” media becomes internet media, those consumer expectations are not going to change. So zero rating is a business requirement.

Also, networks face physical issues. Video is hugely more bandwidth-intensive, but revenue per bit is quite low. There simply is no way media business models work if, in the switch to internet delivery, consumers pay for bandwidth in addition to cost of content.

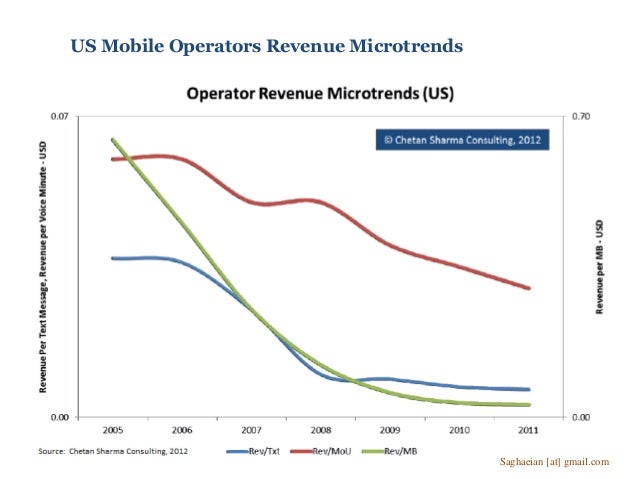

Revenue per bit matters, even if no consumer ever sees such metrics, nor do service providers normally track it.

The revenue per bit problem is easy to describe. Assume an ISP sells a triple-play package for a $130 a month retail price, where each component--voice, Internet access and entertainment video--is priced equally (an implied price of $43 for each component).

Ignore other cost of service elements, such as marketing and content acquisition fees. In term of network usage, that would make sense if each constituent service “consumed” roughly equivalent amounts of capacity, or if retail charging was based relatively directly on consumed bandwidth, and not “perceived value.”

Use of network resources is unbalanced, though. Voice requires use of almost no bandwidth, while video consumers nearly two orders of magnitude more capacity, for each minute of use. Internet traffic is in between, with some apps consuming little capacity (email), some apps consuming a moderate amount of capacity (web browsing) while others are heavy capacity consumers (video).

So, by some estimates, where voice might earn 35 cents per megabyte, revenue per Internet app might generate a few cents per megabyte. Recall that actual revenue per megabyte is statistical: it hinges on how much a user consumes after paying a flat fee for the right to use bandwidth.