It also can be interpreted as an indicator of something much darker: a grasping at flotation devices when a ship is sinking and passengers are in the water. That likely overstates matters a bit.

“It’s time the telecom companies embrace this new reality and rethink the key orthodoxies that have shaped their industry since the first phone call was made about 140 years ago,” McKinsey analysts argue. “If not, the alternative is dire.”

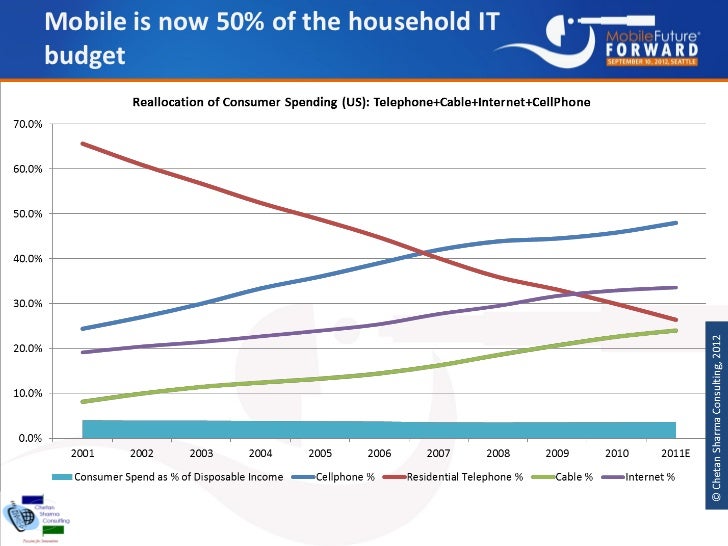

Among the problems is the relative shrinkage of connectivity provider role in the broader internet, communications and content ecosystems.

But the search for new sources of revenue is an urgent concern for an industry whose growth engines change over time, and which faces maturation and decline of all of its core legacy products.

There is more. The connectivity industry’s various segments have unclear positioning in financial markets, which means it is not so easy to value the assets. Nearly everyone would agree that the old valuation model--slow growth, dividend payers--is changing.

But what new positioning the industry eventually assumes is unclear. What if most connectivity providers cease to pay dividends? Aside from the danger of a massive turnover of investor base, what new position will telecom occupy? What other industries will it resemble? And what are the implications for valuation?

Classically, financial analysts have looked at equities are being either growth or value stocks, with high valuation multiples for growth stocks and low multiples for value. Telecom traditionally has been viewed in the value category.

Bu that is changing. To a growing degree, connectivity providers do not pay a dividend. In most cases, that is because cash flows no longer are sufficient to support such practices.

And that calls into question the whole notion of how to think about any connectivity provider’s equity.

Traditionally, if a firm does not pay a dividend, it adds value because it supplies growth. But what if a firm jetisons its dividend but also does not supply growth? What sort of asset is that, and how much should a rational investor be willing to pay for it?

The big question is why own any equity that has neither growth nor a dividend stream. That, in turn, affects ability to borrow money; make acquisitions and even survive as a public company.

Investors understand what a utility is; what a dividend growth company is; they understand cyclical and defensive sectors; growth vehicles as well as income plays.

Perhaps distressingly, they also understand that some whole industries--including capital-intensive industries such as shipbuilding, some forms of transportation, mining, energy exploration and airlines--often have extreme difficulty maintaining profitable operations.

That affects their valuation. So what does that mean for the broad telecom business? We might have to look at analogies; industries that resemble the business much of telecom might become.

For decades, I have considered the airline industry a sort of analogy for telecom. It is a competitive, yet highly capital-intensive business with key governmental oversight and context.

Business strategies also increasingly involve trade offs. No single firm can operate everywhere, supporting every product. So alliances form. Airlines do code sharing and co-marketing, telcos do interconnection agreements and roaming.

Like telecom, airlines have value that is intangible, though generated using quite-physical means. The value is perishable: once an airplane takes off, no more seats can be monetized. Once a minute of time has passed, the value of communications also passes, as well as the ability to monetize.

Some argue telcos should emulate airlines, offering a basic service so bad that customers are willing to pay more to alleviate the pain. Some might argue that is precisely what most telcos already do, unwittingly.

But the key lessons from the airline analogy are clear enough. Valuation multiples are low, as investors have no confidence long-term, stable profits are possible. The industry arguably has lost money much of the time since deregulation, in part because new competitors often enter the market with low price attacks that destroy profit margins.

“We’ve seen this before in other capital-intensive industries,” McKinsey consultants have said. “The airline industry, for example, despite incredible growth in travel during the early part of this century, destroyed economic value until 2015 when, for the first time, the industry-level average return on invested capital (ROIC) was just in excess of its cost of capital.”

So, like it or not, the connectivity industry is going to be looking an awful lot more like the airline industry, with related business problems and valuation assignments, in coming years. What might change what some would consider a trap is a fundamental change of industry business models and revenue sources.

As unpopular as AT&T’s move into content ownership has been, it mirrors the similar successful shift at Comcast, away from distribution and into content-based businesses. That could ease the transition as it means firm valuation has to be a complicated sum of the parts.

Some shrinking or slow-growing parts are matched with stable or fast-growing lines of business. Connectivity always will be key; it simply will not be the sole driver of results.