Most people would agree that understanding means and ends--the relationship between outcomes and actions to achieve those outcomes--make good sense. It does not make good sense to desire an outcome and then take actions which do not achieve the desired outcomes.

That is true everywhere in the connectivity business, but also true in the setting of public policy. Still, we often do not have clarity on the relationship between means and ends. We all believe that quality broadband is important for economic development, job growth, educational outcomes and social equity or inclusion.

But our public policies to support those outcomes might not have a clear means-ends causation link. We can point to correlation between high use of quality broadband and other outcomes (jobs, economic growth, household income, household wealth, health, safety, educational outcomes, inclusion, educational attainment).

But we cannot prove “causation” of those outcomes from the supply and uptake of quality broadband, and likely never will be able to do so, as those outcomes are the result of too many independent variables.

So far, it also appears that our understanding of Covid science and the public policies we see as means to solving the problem of pandemic illness is insufficient for too much confidence about the effectiveness of lockdowns, for example, as a way of slowing disease spread, as logical as that policy seems.

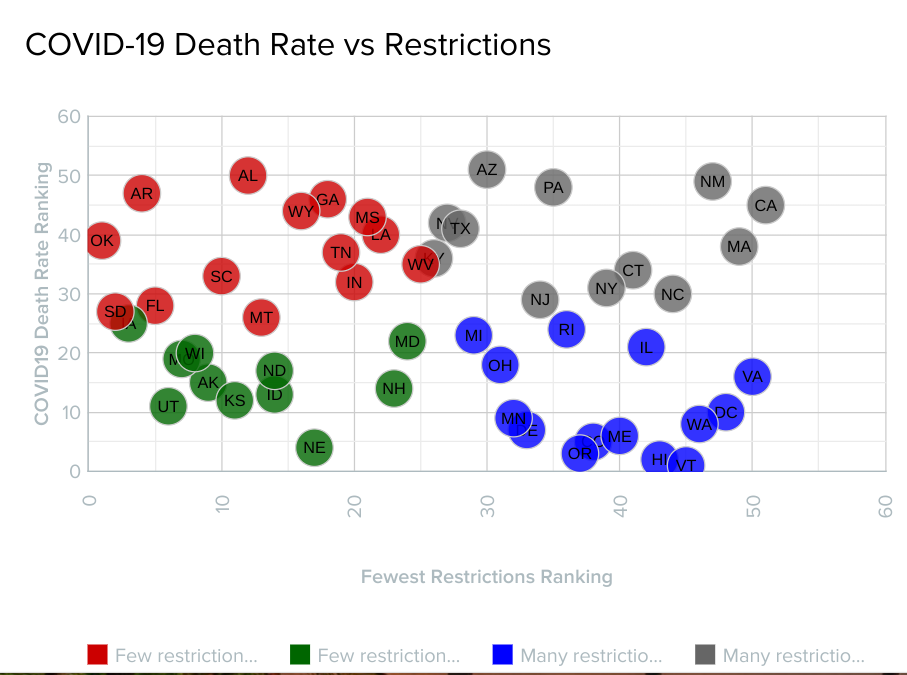

Here is a chart showing the relationship between Covid-19 death rates and the severity of restrictions on business operations, based on data gathered from the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Kaiser Family Foundation, Ballotpedia, McGuireWoods, Editorial Projects in Education, The COVID Tracking Project, National Restaurant Association, Littler Mendelson, JDSupra and Ogletree Deakins by Wallethub.

source: WalletHub

The issue here is no clear pattern. We have states with high death rates with few restrictions and high restrictions. We have lower death rates in states with few restrictions and high restrictions. It is plausible, perhaps even likely, that conditions other than business closures are at work.

This lack of pattern also means we are setting public policy without clear scientific consensus on means and ends, practices and derivative outcomes.

There is a bit more possible clarity when looking at unemployment rates and business closure policies. This analysis shows the relationship between unemployment rates and business closure policies.

source: WalletHub

One would expect higher unemployment in areas with more restrictiveness in terms of business operations. This chart suggests a better relationship, with “many restriction” states tending to have higher unemployment, while “few restrictions” states tend to have lower unemployment, as one might expect.

The problem, so far, is that our expectations about death rates and business closures--death rates “should” be lower when business closures are extensive--do not seem confirmed. That means we cannot be sure business closures actually affect death rates in a direct way.

It is possible that infection rates might have a better means-ends relationship, though. Logically, greater exposure to people should result in higher rates of disease transmission. To the extent that business closures limit exposure, infection rates should be therefore lower.

There is evidence that restaurants and gyms were “superspreader” venues, for example. There also is evidence that restaurant Covid spread rates were extremely low. The point is that the “illness transmission science” is far from settled.

Yet other studies, noting that population density seems to matter.

That noted, some suggest that limiting total restaurant seating capacity might be more effective than total bans on indoor restaurant operations.

But infection rates from other paths, such as between household members, even under lockdown conditions, might well have increased from other policies such as stay-at-home orders.

And studies relying on use of cell phones and mobility also have some methodological issues. People who traveled more had, by definition, more exposure risk. We might not be able to accurately track transmission venues, for that reason.

The point is that the “science” of Covid illness transmission--and the implications for public policy--are not yet largely clear, beyond the general observation that transmission between people is contingent on the number of people one comes into contact with. Population density and duration seem to matter, of course.

But personal behavior also will matter.

Humility about the correctness of our public policy and public health recommendations is called for. To a greater extent than some might be willing to admit, we are guessing about what might work, why and how well.

Other direct consequences, such as job loss, firm bankruptcies, lower economic growth, lower tax revenues, suicides, mental illness and crime rates, also occur because of shutdown policies.

Choice is required and the science does not seem settled sufficiently to adequately inform our choices, well-intentioned though they may be.

That is not a completely unusual context for any public policy, though. We often do not have full knowledge of causation mechanisms, so our policies are, to some extent, guesses.