Very few issues seemingly are more contentious than the issue of whether internet access prices are high or not; rising or not. Internet service providers do not wish to be accused of price gouging; policymakers do not wish to be accused of not doing enough; some policy advocates must argue there is a problem to be solved, or there is no issue to debate.

Nor is this an easy matter to quantify. If one points out that price inflation has occurred for most of modern history, then of course “prices” will be higher, not lower, over time.

U.S. consumer prices in 2022 are 11.77 times higher than average prices since 1950, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index.

source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

General U.S. price levels since 1996, when many people started buying internet access, have increased almost fifty percent. So arguing that prices--any prices--have increased over the last decade, several decades or longer does not mean much.

All prices have increased.

source: OfficialData.org

The only meaningful issue is whether prices for some products, such as home broadband, have increased more, the same or less than the average for all consumer prices. Nor is that an easy exercise.

Methodology also matters.

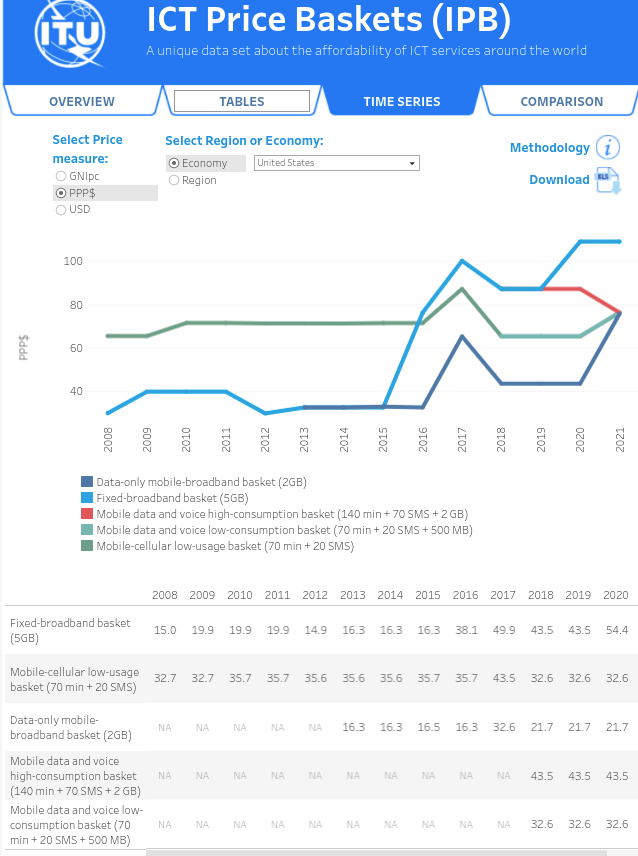

The International Telecommunications Union says that, in the U.S. market, the prices for the lowest-priced plans offering at least 5 Gbytes of usage have increased from less than $40 per month in 2008 to more than $100 a month in 2020.

That seems wildly incorrect. That might be the case for gigabit services--which can approach $100 a month--but cannot be correct for the budget plans that are in the $30 a month level. The methodology is off, as Comcast, the largest U.S. ISP, only charges $30 a month for services operating at 100 Mbps. To be sure, Comcast also says those prices are good only for one year, with sharp price increases after 12 months.

Comcast says its 100-Mbps plan will grow to $81 a month after 12 months. The issue is that it would be hard to find anybody who actually pays that amount for a 100-Mbps service, even after a 12-month period.

The average U.S. home broadband service costs about $64 a month. If the cost of the lowest-priced plan really were more than $100 a month, as the ITU analysis suggests, the “average” U.S. price could not be as low as $64. By definition, the average would have to be much higher.

According to Openvault, only about 20 percent of U.S. households purchased services operating at 100 Mbps or less in the second quarter of 2021 and only 18 percent in the third quarter of 2021 and 17 percent by the fourth quarter of 2021.

source: Openvault

source: ITU

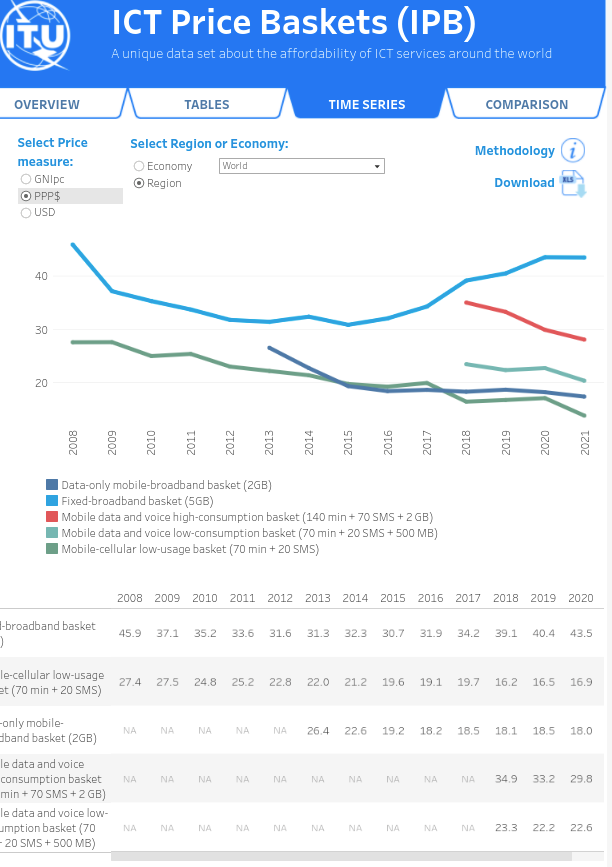

Other issues must be confronted when comparing prices across countries. Adjusting for currency and living cost effects, the International Telecommunications Union, for example, says mobile prices (not adjusted for inflation) have dropped, while fixed network prices for the lowest tier of service have climbed a bit since 2015, but only after having dropped since 2008.

Still, prices are lower than in 2008, all that noted.

source: ITU

Keep in mind that this analysis is only of the cheapest plans in each country offering at least 5 Gbytes of usage and a minimum speed of 256 kbps, supplied by the largest internet service provider in each market.

The analysis is not of the service plans “most consumers buy.” The plans are based only on posted retail tariffs and do not include any discounts customers may have based on promotions or other criteria. Nor does the data take into account whether plans offered by all providers that are not the “biggest” in each market. Nor does the analysis include the prices paid by consumers on the most-popular plans, using any discounts or promotions.

There are other important drivers at work, as well. Since 2008, ISPs in developed countries have been rapidly increasing “typical” speeds, while consumers have been gradually changing the service plans they buy, shifting from lower-speed plans to higher-speed plans that cost more.

Beyond all that, the latest ITU data on U.S. home broadband plans seems wildly incorrect.