One frequently hears that home broadband or internet access is a utility similar to electricity, gas, water, sewers, phone lines, roads, seaports or airports. It is not always clear what proponents of viewing home broadband “as a utility” have in mind when they say such things.

Some might mean home broadband should be, or is, a public utility in the sense of “common carrier” with obligations to serve the general public. Others might mean essential or regulated in terms of price or conditions of service. Others might fix on the used everyday sense of the term.

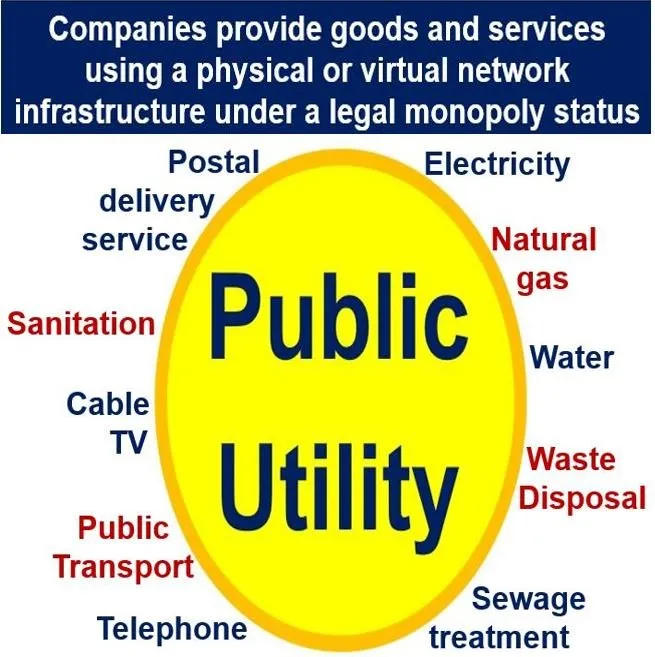

Classically, the term referred to industries that operated as monopolies, often because they are capital intensive and difficult to replicate.

source: Market Business News

As it pertains to “home broadband,” generally the term refers to fixed network supply of home broadband, not mobile network supply.

The common unstated reason for calling for utility treatment seems to be the expectation that this means lower prices. Actually, it is not clear how prices might be affected. True, some elements of consumer service were price controlled. But other elements were horrendously expensive.

Most of us are too young ever to have experienced “connectivity services” as a public utility. But prices were not uniformly low.

In 1984, before the breakup of the U.S. AT&T monopoly, calling between states cost about 90 cents a minute. In 1955, a phone call between Los Angeles and San Francisco (not even interstate) cost about 70 cents a minute, not adjusted for inflation.

In 2022 currency that would be about $7.75 per minute. So, no, prices were not uniformly lower under monopoly or public utility regulation.

Of course, that was by policy design. High long distance charges and high business services were intended to subsidize consumer local calling.

Were home broadband to become a regulated service, something similar would happen. While prices for some features and plans might be price controlled, other elements of value would increase sharply in price.

And price is only one element of value. Service innovation was sharply limited in the monopoly era. In the U.S. market, consumers could not own their own phones, or attach third party devices to the network. All consumer premises gear had to be purchased from the phone company, for example.

To be sure, AT&T Bell Labs produced many innovations. But they were not directly applied to the “telephone service” experience. Those included Unix, satellite communications, the laser, the solar cell, the transistor, the cellular phone network, television and television with sound.

Though ultimately quite important, none of those innovations arguably applied directly to the consumer experience of the “phone network” or its services.

The point is that monopoly regulation tends to produce varied prices for different products (some subsidized products, some high-cost products), but also low rates of innovation in the core services.

Utility regulation? It would not wind up being as beneficial as some seem to believe.