Very few major social problems have clear and uncomplicated causal relationships, which makes virtually impossible the task of determining whether public policies actually work, or not.

For complex social problems like poverty, housing, crime, education, carbon reduction or traffic, it remains quite difficult to prove causal links between policies and outcomes. Basically, policies are tried without any real way of knowing whether they work.

Contrast that with a few instances where the primary causation mechanisms are relatively clear. The causal link between smoking tobacco and various health issues like lung cancer, heart disease, and respiratory problems is well-established.

There is a direct causal relationship between alcohol consumption and impaired driving leading to accidents and fatalities.

Conditions such as scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) or rickets (vitamin D deficiency) have clear causation mechanisms related to lack of specific nutrients in the diet. Likewise, the danger of lead exposure, especially in children, is clear.

The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture has a direct causal relationship with the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Home broadband supply now is likely one problem for which we know at least one causal relationship, namely that financial subsidies work. Since the cost of home broadband infrastructure is directly related to population density, financial subsidies are required in low-density rural areas.

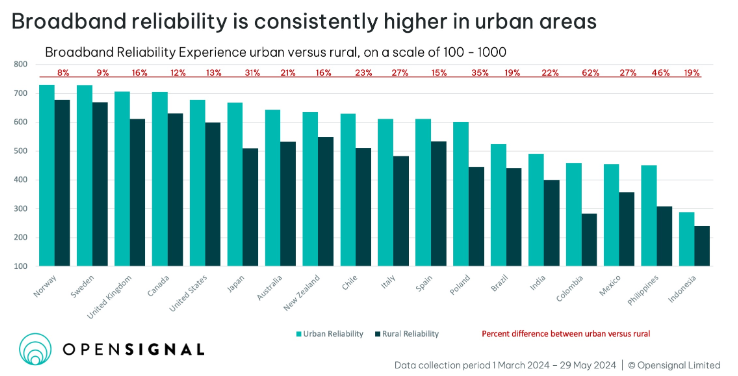

Urban households tend to have access to better home broadband than households in rural areas, rural residents might note, policymakers might agree and OpenSignal says.

And though there are correlations between income, education and age in any market, “income levels are less predictive of reliability than density,” OpenSignal notes.

It might be noteworthy that although sharing of network infrastructure often is touted as a way of reducing the cost of home broadband infrastructure, OpenSignal studies find there is no correlation between network infrastructure sharing and either high reliability or a narrow digital divide. “Countries with limited infrastructure sharing but targeted subsidies for private rural investment mostly perform better than those relying on widespread infrastructure sharing,” OpenSignal notes.

Topography and density are key factors in the size of the divide between urban and rural home broadband experience.

Markets with highly-concentrated populations in urban areas show small gaps between urban and rural reliability, and spread-out middle-income countries with difficult terrain show big gaps. “But a few countries with lots of medium-density areas, like the U.S., and Spain, have relatively small digital divides,” the firm says.

In fact, the U.S. market might better be characterized as having huge low-density areas. population density has a huge impact on the cost of building new networks, mobile or fixed, but especially fixed networks.

U.S. population density is quite thin across most of its geography, which directly affects the cost of building broadband networks, as hefty subsidies are required to reach the last one percent or two percent of remote locations.

And the United States has a huge percentage of its land mass that is thinly settled, if at all settled. In Canada, 14 percent of the people live in areas of density between five and 50 people per square kilometer. In Australia, 18 percent of people live in such rural areas.

In the United States, 37 percent of the population lives in rural areas with less than 50 people per square kilometer.

Put another way, less than two percent of Canadians and four percent of Australians live in such rural areas. In the United States, fully 48 percent of people live in such areas.

Put another way, about six percent of the U.S. land mass is “developed” and relatively highly populated. Those are the areas where it is easiest to build networks. But about 94 percent of the U.S. land surface is unsettled or lightly populated, including mountains, rangeland, cropland and forests. And that is where networks are hardest to build and sustain.

So it should not at all be surprising that broadband reliability is, on average, 23 percent higher in urban areas than in rural areas across all markets we analyzed,” say analysts at OpenSignal. The firm uses a 100 to 1000 point scale to measure broadband experience in a typical household where multiple devices are used simultaneously.

The metric is based on ability to connect (uptime); ability to complete tasks and speed, latency, jitter performance.

source: OpenSignal

Financial subsidies for service providers in rural areas are one way governments try to close digital divides, and arguably are the most effective ways to do so. Whether in the form of subsidies for anchor institutions or per-passing or per-connection support is the clearest way to reduce the cost of rural infrastructure for suppliers.

Beyond that, policymakers often try to encourage competition and promote deployment of alternative platforms (satellite, fixed wireless, mobile access).

Governments can help communities create cooperatives; reduce permitting and other regulatory costs or train people to use broadband. But perhaps nothing works so well as simple subsidies, for the simple reason that population density and network cost are inversely related.

High population density leads to lower costs; low density leads to higher costs. So subsidies for home broadband in rural areas are a relatively clear example of cause-and-effect relationships.