When market researchers aggregate a whole bunch of different revenue streams together, and then call them all “one market,” it is a clear sign that each of the constituent markets is small. Only by aggregating can a market of reasonable size be shown to exist.

That arguably is the case for a host of services collectively lumped into the hosted UC or hosted PBX category.

In 2008, the combined business phone system, conferencing, messaging, unified communications, contact center, collaboration, rich media, email and calendaring markets collectively amounted to perhaps $29 billion globally.

By 2014 the market perhaps had shrunk to perhaps $19 billion, according to some estimates.

In fact, despite hyperbole about “huge new markets,” the truth is that the broad UC and IP communications businesses are not that big. In fact, one might argue that traditional business voice systems are a flattish business, while all manner of software-based services might be where the growth is happening.

Bottom line, is the market still growing? Probably, but only because so many categories are lumped together. As sales of business phone systems fall, hosted alternatives still seem to be growing, if rather slowly, on a global basis.

Hosted PBX revenues globally might only be in the $10 billion range, meaning the market is small, in most countries. If the U.S. market represents half the world total, then hosted PBX represents $5 billion or so in annual revenue. That is significant for some specialists, but a small bogey for the whole U.S. service provider market.

Also, a significant portion of reported “hosted UC” or “hosted PBX” revenue actually consists of SIP trunking, an access service, not a “voice” service. By some estimates, North American hosted PBX revenue--subtracting out the access portion--might be about $4 billion annually.

The ultimate issue is total potential market size, and what percentage of that total hosted services can address. Some estimate the total addressable North American market is about 140 million business lines, for all solutions. So far, hosted services have gotten about 12 percent of that total.

It still might be useful to estimate what percentage of hosted services adoption is reasonable, since, at some point, it still appears that “owning” phone systems, rather than “renting” services, makes sense.

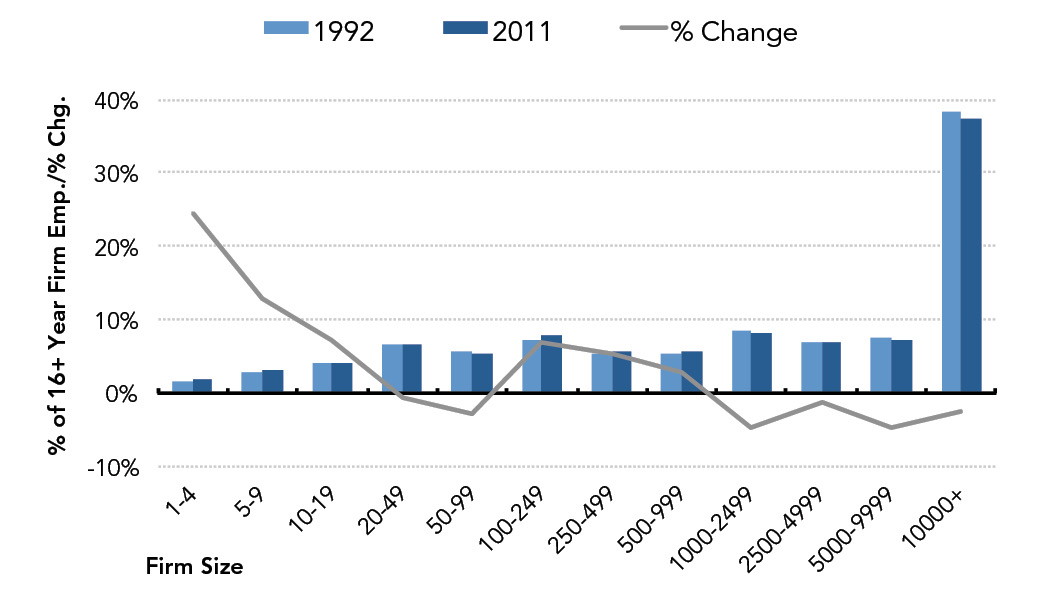

Most workers (more than 70 percent) are at firms that have been in business six or more years. Roughly speaking, you can assume that roughly 70 percent of demand for “lines” and services therefore also exists at those firms.

Nearly 40 percent of all U.S. employees work for firms of at least 10,000 employees. Those are the employees working at firms most likely to benefit from “owning” switches rather than renting services, for the most part.

At least so far, most hosted PBX adoption has occurred at firms with fewer than 50 employees, nearly 70 percent, by some estimates. Roughly 17 percent of hosted PBX adoption occurs at firms with 50 to 500 users, while 15 percent of demand has come from firms with more than 500 users.

And that points to an apparent limitation. Only about 25 percent of business employees work at firms with 100 or fewer employees.

If the economics of owning versus renting services do not change much--if it continues to make financial sense for larger enterprises to won their switches, then a substantial part of the business communications market will remain largely “off limits” for hosted services adoption.

It will continue to make sense for small, young and fast-growing firms to choose a hosted solution. The issue is simply that most people work at large firms where hosted alternatives are not necessarily cost competitive, whatever “soft” advantages (moves, adds, changes) exist.

Distribution of Total Private-Sector Employment by Firm Age

Distribution of Employment at 16+ Year Firms by Firm Size

Whatever you think might be happening in the broad “unified communications or business voice” markets, one fact has not changed over the last decade: as important as the segment is for some suppliers in the market, the categories are relatively small, within the context of the whole communications market, or even within the business communications segment.