Frontier Communications Corporation has lent its name to "FTR Energy Services," as part of a marketing agreement with Crius Energy. That doesn't mean Frontier Communications is "getting into the business of retailing energy services."

It means Frontier is lending its name and marketing muscle, presumably, to a third party affiliate that will sell "clean energy" including electricity and natural gas to customers.

FTR Energy Services is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Crius Energy and will launch in select markets in November 2012.

The company will initially provide 100-percent "green electricity" to customers in New York and Ohio, and clean-burning natural gas to customers in Indiana.

Some will be glad to hear that Frontier has not made a direct effort to add energy retailing to its triple play or quad play offers. At various times over the last couple of decades, telecom service providers have dabbled with the notion of adding energy services to the retail menu, as some also had dabbled at home security.

Financial results have been quite mixed. None of that is stopping cable companies and telcos from taking another look at home security, particularly as broadband access, smart phones, tablets and video now offer opportunities not available before.

The historic problem with energy services is the low profit margin. Traditionally, a service provider would wholesale capacity from a utility, then offer a discount to consumers. The problem always has been the thin profit margins.

So some will be happy Frontier has not gotten enamored of that approach. Instead, it simply seems to be testing a way of earning a bit of incremental revenue from a marketing partnership.

The more lucrative opportunity might arise from selling automated meter reading or energy management services to firms such as Crius, at some point.

Monday, October 29, 2012

Frontier Communications Lends Name to Retail Energy Services

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Games Lead App Usage on Both Smart Phones and Tablets

General patterns of smart phone use, across a typical day, resemble the usage pattern for tablets, according to Flurry, with one salient exception: tablets are used less than smart phones during the workday, and more than smart phones during the evening hours, Flurry says.

At a high level, consumers spend more time using tablets for media and entertainment, including games (67 percent), entertainment (nine percent) and news (two percent) categories which account for nearly 80 percent of consumption on tablets.

Smart phones claim a higher proportion of communication and task-oriented activities such as social networking (24 percent), utilities (17 percent), health and fitness (three percent) and lifestyle (three percent), representing nearly half of all usage on smart phones.

Games are the most popular category on both form factors with 67 percent of time spent using games on tablets and 39 percent of time spent using games on smart phones.

Consumers also spend 71 percent more of their time using games on tablets they spend doing so on smart phones.

At a high level, consumers spend more time using tablets for media and entertainment, including games (67 percent), entertainment (nine percent) and news (two percent) categories which account for nearly 80 percent of consumption on tablets.

Smart phones claim a higher proportion of communication and task-oriented activities such as social networking (24 percent), utilities (17 percent), health and fitness (three percent) and lifestyle (three percent), representing nearly half of all usage on smart phones.

Games are the most popular category on both form factors with 67 percent of time spent using games on tablets and 39 percent of time spent using games on smart phones.

Consumers also spend 71 percent more of their time using games on tablets they spend doing so on smart phones.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

France Wants Google to Pay for Links to News Stories

President Francois Hollande told Google CEO Eric Schmidt that France would pass legislation to force Google o pay for displaying links to news articles unless it struck a deal with French media outlets providing those entities payment for linking, essentially. Google obviously doesn't agree with the policy.

Press associations in France and other European countries want Google to pay when it displays links to newspapers in Internet search results.

The tussle isn't new. Owners of copyrighted material, especially those losing revenue and relevance to online media, obviously would prefer to be paid by search engine application providers. That revenue would help offset revenue losses in other areas, including subscriber fees and advertising.

Google, of course, prefers to argue it merely is indexing and "pointing users to" such sites. Owners of newspaper or magazine sites are free to put their content behind a "pay wall," of course.

It is reminiscent of the imilar friction between Internet service providers and third party applications that are delivered over Internet service provider networks. In the end, it's all about the money.

Press associations in France and other European countries want Google to pay when it displays links to newspapers in Internet search results.

The tussle isn't new. Owners of copyrighted material, especially those losing revenue and relevance to online media, obviously would prefer to be paid by search engine application providers. That revenue would help offset revenue losses in other areas, including subscriber fees and advertising.

Google, of course, prefers to argue it merely is indexing and "pointing users to" such sites. Owners of newspaper or magazine sites are free to put their content behind a "pay wall," of course.

It is reminiscent of the imilar friction between Internet service providers and third party applications that are delivered over Internet service provider networks. In the end, it's all about the money.

Google says they send four billion clicks per month to publishers and one billion of those clicks come from Google News. Google News is free, there are no ads on Google News, but yet Google has an AdSense program that paid out over $6.5 billion to U.S. publishers from in 2011.

French news publishers obviously feel otherwise.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

What Will "Nomadic Web" Mean?

Even if the answer is, for the most part, yes, the speed of this transformation and the route it will take are far from certain, McKinsey analysts say.

The fates of many leading stakeholders could be affected, for better or worse. The reason Google, Apple, Yahoo, Amazon, Facebook and many other application providers are racing to secure a foothold in mobile apps is that it is not certain PC-based business models are completely transferable to the mobile domain.

Also, tablets are not used for the same reasons, or at the same places, as PCs and notebooks have been used.

"Location," directions and other attributes of the "out and about" nomadic web likewise are different from traditional "search" and "information requests" typical of the desktop web. There is a greater commercial angle, for example, as people more often are looking for something to buy now, someplace to go, right now or someplace to go soon.

Nor is it clear how consumer use of access networks might change, from fully mobile to untethered. There will be some consumers who might find that mobile broadband, possibly using personal hotspot features, are suitable replacements for fixed network access.

If people begin to rely on mobile web for most of what they do on the web, that could dramatically change expectations about bandwidth growth. To be sure, there are lots of reasons for consumers to use fixed connections.

But Austria, though an exception to the current rule, already features more people using the mobile web than fixed connections to the web. Access aside, the design and use of applications in a nomadic context is different from apps used in a PC mode.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

New Nexus 4, Nexus 7, Nexus 10 Will be Sold Direct on Google Play

Google's new Nexus 4 smart phone will be sold unlocked and without contract on the Google Play app store.

Google's new Nexus 4 smart phone will be sold unlocked and without contract on the Google Play app store. The 8GB model will sell for $299 while the 16GB model will sell for $349, beginning on November 13, 2012, in

the United States, United Kingdom, Australia,France, Germany, Spain and Canada, Google says.

The 16GB version also will be sold by T-Mobile USA for $199, with a two-year contract.

, a

Google also unveiled the Nexus 7, a seven-inch screen tablet, as well as the Nexus 10, a tablet with a 10-inch screen.

The Nexus 7 featuring 16GB of memory will sell for $199, while the 32GB version will sell for $249; available in the U.S., U.K., Australia, France, Germany, Spain, Canada and Japan, and also through retail partners Gamestop, Office Depot, Office Max, Staples and Walmart.

The Nexus 7 with 32GB and mobile data will sell for $299, unlocked, starting Nov. 13, 2012, on the Google Play store in the U.S., U.K., Australia, France, Germany, Spain and Canada.

The Nexus 10 with 16GB will sell for $399; the 32GB model will sell for $499; available on Nov. 13, 2012, in the Google Play Store in the U.S., U.K., Australia, France, Germany, Spain, Canada and Japan.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

How Much New Revenue Must U.S. Telcos Generate, Over the Next 5 Years?

Perhaps $33 billion, one might argue. That is the amount of voice revenue U.S. service providers (fixed and mobile) will lose between 2010 and 2015, Verizon says. And the good news is that it probably won’t be a problem, at least for the leading mobile service providers.

The precedent in the U.S. market was long distance revenue. Over about a decade, service providers moved from earning about half of their total revenue from long distance, to earning about half their revenue from mobile services.

In North America, some believe voice connections should shrink by about half between 2007 and 2016, a period of nine years, according to Pyramid Research.

As a rough illustration, look only at the U.S. market, where some have forecast annual six percent declines in fixed network voice revenue.

If that proves to be accurate, then U.S. fixed network voice providers might have to replace about $33 billion in annual revenues between 2010 and about 2017, while mobile service providers might have to replace about $5 billion in voice revenues.

To be sure, much of the immediate answer already is in place, namely video entertainment, fixed broadband access, mobile data and possibly other contributors such as hosting and data center revenues.

And most would say that level of revenue replacement clearly is “doable.”

Insight Research, an aggressive optimist, predicts U.S. service provider revenue could double in just the next five years. The firm predicts that, between 2011 and 2016, North American carrier revenue will rise from $287 billion to $662 billion, representing 11 percent compound annual revenue growth.

That rapid growth, on a compound basis, would lead to a doubling of industry revenue in five years. That doesn't mean providers in every segment will benefit equally. But overall revenue growth will happen mostly at the largest service provider entities.

The forecast explicitly assumes that U.S. service providers successfully will grow new revenues at a rate fast enough to compensate for weakening voice revenues, Insight Research believes.

In one sense, it therefore is possible to suggest that U.S. service providers will, once again, succeed in transforming their businesses, as they did when long distance revenue shriveled and was replaced by mobile revenues.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

How Many U.S. Mobile Service Providers are Optimal?

With the recent mergers of T-Mobile USA and MetroPCS, and the purchase of Sprint by Softbank (assuming both transactions pass regulatory muster), there is once again an active discussion in many quarters about the future shape of the U.S. mobile service provider business.

What seems a safe observation, though, is that the number of successful mobile service providers will be few in number. The only question is “how few?” In many markets, there are four to five major providers, in terms of market share. But just how stable a market that is is questionable.

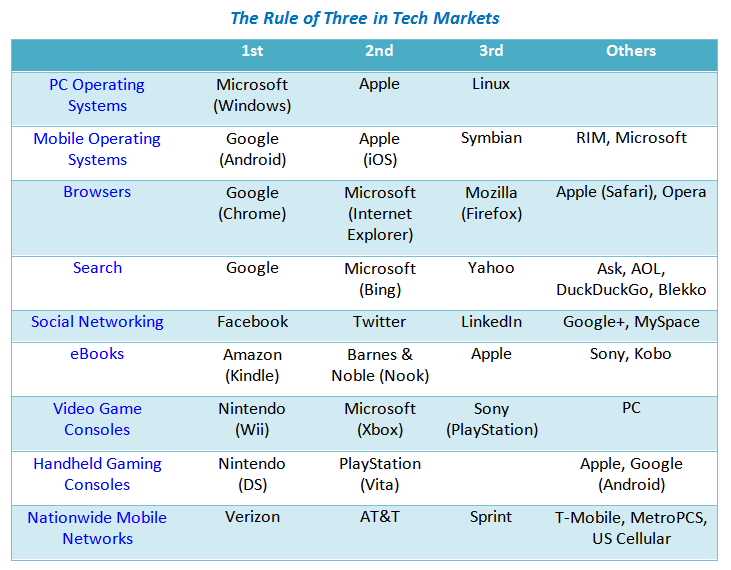

The Rule of Three holds nearly everywhere. While the percentage market share might vary, on an average, the top three mobile service providers control 93 percent of the market share in a given nation, irrespective of the regulatory framework.

Some might argue that scale effects account for the relatively small number of leading providers in many capital-intensive or consumer electronics businesses. At some point, the access business can have only so many facilities-based providers before most companies cannot get enough customers to make a profit.

Eventually, only the top three service providers control the majority of the market. There are niches that others occupy but they are largely irrelevant to the overall structure and functioning of the overall market.

Younger mobile markets can see five to six significant contestants at first, each with at least 10 percent market share. Over time, that winnows to three, history suggests. To be sure, there are plenty of markets where four to six major contestants operate, but even there, about three firms control most of the actual customer and market share.

The competitive equilibrium point in the mobile industry seems to when the market shares of the top three providers are 46 percent:29 percent and 18 percent, some might argue. At such a structure, the top three providers have 93 percent of the market.

That roughly corresponds with a rule of thumb some of us learned about stable markets. The rule is that the top provider has twice the market share of the contestant in second place, while the number-two provider has about twice the market share of the number-three provider.

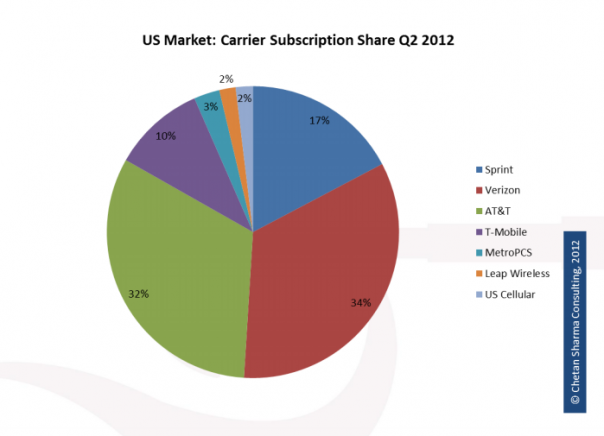

That suggests the U.S. mobile market still has room to change. At the moment, Verizon Wireless has perhaps 34 percent share, while AT&T has about 32 percent share. Sprint has about 17 percent, while T-Mobile now has about 13 percent.

Classic theory would suggest the ultimate market share could approach a market with the top-three providers having a market share relationship something like 50:25:12.

Real markets always vary from “textbook” predictions, but a “rule of three” market structure seems likely.

That would have highly-significant implications for the four current U.S. providers that today represent 93 percent of all subscribers. One would presume the long-term viability of Sprint and T-Mobile USA is questionable.

What seems a safe observation, though, is that the number of successful mobile service providers will be few in number. The only question is “how few?” In many markets, there are four to five major providers, in terms of market share. But just how stable a market that is is questionable.

The Rule of Three holds nearly everywhere. While the percentage market share might vary, on an average, the top three mobile service providers control 93 percent of the market share in a given nation, irrespective of the regulatory framework.

Some might argue that scale effects account for the relatively small number of leading providers in many capital-intensive or consumer electronics businesses. At some point, the access business can have only so many facilities-based providers before most companies cannot get enough customers to make a profit.

Eventually, only the top three service providers control the majority of the market. There are niches that others occupy but they are largely irrelevant to the overall structure and functioning of the overall market.

Younger mobile markets can see five to six significant contestants at first, each with at least 10 percent market share. Over time, that winnows to three, history suggests. To be sure, there are plenty of markets where four to six major contestants operate, but even there, about three firms control most of the actual customer and market share.

The competitive equilibrium point in the mobile industry seems to when the market shares of the top three providers are 46 percent:29 percent and 18 percent, some might argue. At such a structure, the top three providers have 93 percent of the market.

That roughly corresponds with a rule of thumb some of us learned about stable markets. The rule is that the top provider has twice the market share of the contestant in second place, while the number-two provider has about twice the market share of the number-three provider.

That suggests the U.S. mobile market still has room to change. At the moment, Verizon Wireless has perhaps 34 percent share, while AT&T has about 32 percent share. Sprint has about 17 percent, while T-Mobile now has about 13 percent.

Classic theory would suggest the ultimate market share could approach a market with the top-three providers having a market share relationship something like 50:25:12.

Real markets always vary from “textbook” predictions, but a “rule of three” market structure seems likely.

That would have highly-significant implications for the four current U.S. providers that today represent 93 percent of all subscribers. One would presume the long-term viability of Sprint and T-Mobile USA is questionable.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Gary Kim has been a digital infra analyst and journalist for more than 30 years, covering the business impact of technology, pre- and post-internet. He sees a similar evolution coming with AI. General-purpose technologies do not come along very often, but when they do, they change life, economies and industries.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Will AI Fuel a Huge "Services into Products" Shift?

As content streaming has disrupted music, is disrupting video and television, so might AI potentially disrupt industry leaders ranging from ...

-

We have all repeatedly seen comparisons of equity value of hyperscale app providers compared to the value of connectivity providers, which s...

-

It really is surprising how often a Pareto distribution--the “80/20 rule--appears in business life, or in life, generally. Basically, the...

-

One recurring issue with forecasts of multi-access edge computing is that it is easier to make predictions about cost than revenue and infra...