Is Nokia in some ways a metaphor for Europe’s mobile industry? On the supply side, what I mean by that is simply that Nokia had such a great understanding and leadership of the feature phone market that it could not shift to the different smart phone market.

Is Nokia in some ways a metaphor for Europe’s mobile industry? On the supply side, what I mean by that is simply that Nokia had such a great understanding and leadership of the feature phone market that it could not shift to the different smart phone market.

On the demand side, it might be argued that consumer preferences in Europe and the United States simply are different. Nokia had such a lead in many markets because Nokia supplied what consumers wanted.

In that sense, are we at a point where European consumer demand for 4G services actually is limited, in the way demand for 3G once was limited, irrespective of supply?

In other words, though regulators and mobile service providers alike seem to agree more can be done to stimulate deployment of 4G Long Term Evolution networks in Europe, one wonders whether consumer preferences create barriers in that regard.

In other words, though regulators and mobile service providers alike seem to agree more can be done to stimulate deployment of 4G Long Term Evolution networks in Europe, one wonders whether consumer preferences create barriers in that regard.

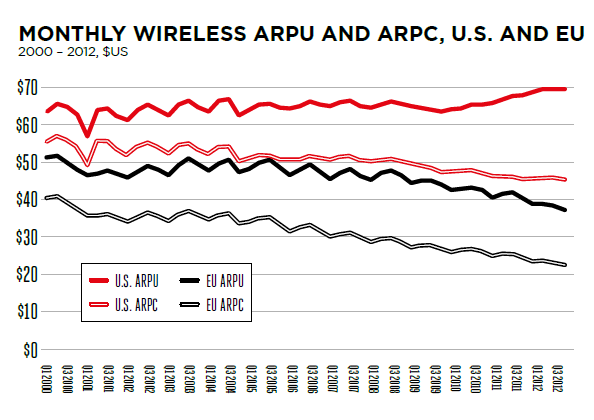

U.S. consumers use five times more voice minutes and nearly twice as much data as European consumers on a monthly basis. But Stéphane Téral, Infonetics Research principal analyst notes that mobile broadband is the revenue growth driver, even if European consumers seem to prefer to spend less on mobile Internet access than U.S. consumers prefer.

On the other hand, the question might be whether, at the moment, 3G is viewed by consumers as satisfactory. In the absence of a 4G alternative, it is hard to know for sure.

LTE broadband is growing the fastest of any mobile services category, Téral says. That might be why AT&T sees European expansion as potentially lucrative, and why regulators want faster 4G network deployment.

U.S. consumers might be more engaged with Internet apps than consumers in Europe might be, and use and value mobile broadband and fast data access more than European consumers do, at least for the moment.

That is not a matter of “ahead or behind,” but simply of “difference.” And demand can change.

As U.S. consumers once valued mobile phones and text messaging less than Europeans, that eventually changed. European demand for LTE 4G could change as well. The issue, for some, might be “when” demand changes.

To be sure, a lag in LTE is viewed as a problem. In May 2013, GSMA issued a report arguing Europe was “falling behind” the United States in next generation mobile deployment. Ignoring for the moment past claims of that sort that had the United States lagging Europe, which only suggests markets change, the GSMA worries about fourth generation network in Europe.

On average, U.S. consumers spend more each month than their EU counterparts and use mobile services much more intensely, consuming five times more voice minutes and nearly twice as much data.

Average mobile data connection speeds in the U.S. are now 75 per cent faster than those in Europe and by 2017 will be more than twice as fast.

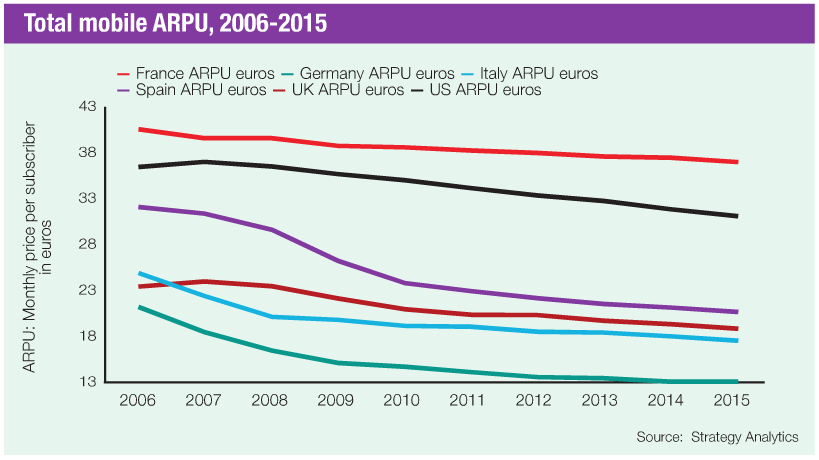

One expression of the problem is that mobile Internet access revenue in Europe is not growing fast enough to offset losses of voice revenue, though some hope the decline can be arrested.

But why that is the case is the strategic issue, with respect to 4G investment. Perhaps mobile data consumption is not growing as fast because that is what consumers prefer, and not because the networks are limited in some way. If that is the case, building 4G will only cause more financial losses.

And it might be hard to dismiss the argument that consumers are being careful about paying more for mobile service because of current economic conditions, suggesting a slower introduction of LTE is not as big a problem as the level of consumer demand.

Mobile accounts continue to shrink in Spain, for example, a problem that some hoped had reached an end in May 2013, when accounts actually grew after 10 months of decline. But June 2013 showed another drop.

Spanish mobile accounts in service were 51.9 million at the end of June 2013, down 4.9 percent from 54.6 million for the same month of 2012. With the exception of acquisition-aided growth, every mobile operator lost customers.

Movistar, Spain’s biggest mobile operator, lost 102,000 lines during the month, Vodafone lost 90,000, and Yoigo lost 121,900 lines. Orange gained 41,000 based on acquired firm Simyo.

EU27: Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) 2007-2010