What strategy should fixed line telcos and mobile service providers take towards their legacy voice and messaging revenues? Should they invest more and add features to revamp the products, or essentially harvest them?

In fact, some might say the problem is stark: can anything be done to arrest the decline of voice and messaging revenues?

The question is far from academic, and far from new.

The same questions could have been asked about long distance revenues in the decades following 1984, in the U.S. market, when a long and persistent decline in voice revenue began.

One might argue that the same fundamental question was relevant: what can or should be done to enrich and remake long distance service to reverse the revenue decline? Can “long distance” be recreated to produce new products?

In many ways, the problem was even simpler than faced by service providers today. There were no convenient or usable alternative communication modes. There was no way to substitute email or instant messaging, text messaging, Google Hangouts or IP voice for long distance calling.

The challenge service providers face today is far worse. There are viable substitutes, including substitutes that arguably already incorporate multi-mode features (image, voice, text, image, video). Most of those substitutes are available to use for no incremental cost.

Nor, in the two decades following 1984, had mobile communications become a widespread, affordable alternative for voice communications.

Though it provides only one historical point of reference, the lesson is that virtually nothing could be done to halt the decline in long distance gross revenues or profit margin.

“Long distance” as a product simply reached a point of maturity, and began to decline, in part because monopoly supply was replaced by competitive supply, and then affected even more by the emergence of viable product substitutes.

To be sure, suppliers can attempt, and advisors can recommend, that any number of things be done to upgrade and reshape the value proposition for carrier voice and messaging. That is the essence of the “don’t be a dumb pipe” advice.

For example, Telco 2.0 analysts argue that telcos could salvage about $80 billion of potentially lost voice and messaging revenue globally by taking a new approach to retail prices and bundles, service enablement, use of WebRTC and VoLTE, creative approaches to own brand OTT services, and a greater focus on enterprise communications.

Those efforts could slow the decline of voice and messaging revenues and allow telcos to build new communications services for both consumer and enterprise customers, many will argue.

Up to a point, that advice might produce results. But history is a stern taskmaster. Virtually nothing, in a far-easier competitive environment, “saved” long distance. Instead, the business simply was harvested.

That, in fact, is largely what service providers now do for international long distance. In some markets, such as within the boundaries of the United States, “long distance” has disappeared as a product, and is simply a feature of calling.

Some might argue that is, in the end, what will happen with carrier voice and messaging. In fact, some carriers already have moved to price the features that way. Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility, as part of their shared data plans, simply make unlimited domestic voice and text messaging a basic, unlimited-use feature of network access.

That doesn’t mean the end of what any service provider might do to create new products or services incorporating voice or messaging, or making those features available to third parties, for a fee.

The issue, strategically, is the balance of harvesting and investing. Some might argue a firm faced with a mature product, in decline, should invest in growing new lines of business and creating new sources of revenue, rather than “overinvesting” in a product whose revenue prospects are challenged.

It’s an eminently practical issue. Globally, telcos could lose up to $172 billion from voice and messaging revenues in five years, according to researchers at Telco 2.0.

“We expect a total decline in voice revenues between -25 percent and -46 percent on a $375 billion base between 2012 and 2018,” Telco 2.0 says.

To be sure, mobile voice and messaging remain growth markets in developing countries and regions.

The issue is how much can be done in developed markets, in any of the legacy markets.

Few would argue that product life cycles exist, even in telecommunications, and that new revenue sources have to be developed and created.

The issue is whether “voice and messaging” are mature products to be harvested, or can be changed into new growth products.

We should get some indications of carrier thinking as the composition of capital investment evolves over the coming decade. For the moment, the notable changes are that although service providers will spend more on most equipment segments in 2013, the exceptions are voice, broadband aggregation, and video infrastructure, according to Infonetics Research.

That does not offer definitive proof about service provider strategies, as most efforts to add value to voice and messaging are software matters, not issues of hardware investment.

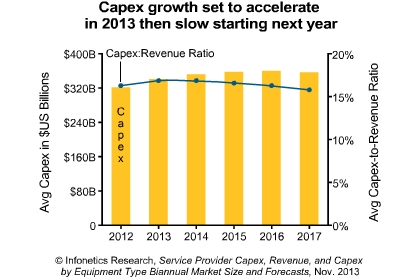

Global telecom capital investment is set to grow between 2012 and 2017 in absolute terms, though remaining relatively constant in percentage terms, according to the latest forecast by Infonetics Research.

To be sure, the visible changes are at a rather fundamental level, such as decisions to invest more in mobile infrastructure than fixed infrastructure, for example.

China Telecom, for example, the largest provider of fixed-line broadband access to the Internet in China, is likely to reduce its 2014 capital investment for fixed-line broadband Internet access infrastructure by 50 percent.

The reason is a need to shift investment to new Long Term Evolution 4G networks, to catch competitor China Mobile. China Unicom might have to consider such a shift as well.

Also, investment in developing region networks will make sense, because that is where the revenue growth exists.

Global telecom carrier capex is forecast by Infonetics to grow at a two percent compound annual growth rate from 2012 to 2017, reaching US$355 billion.

Much of the spending will be driven by mobile service providers through 2017, though spending by fixed network providers might shrink, a rather direct reflection of the fact that revenue growth is coming from the mobile segment.

Asia Pacific will remain the region with the highest capex spending through at least 2017.

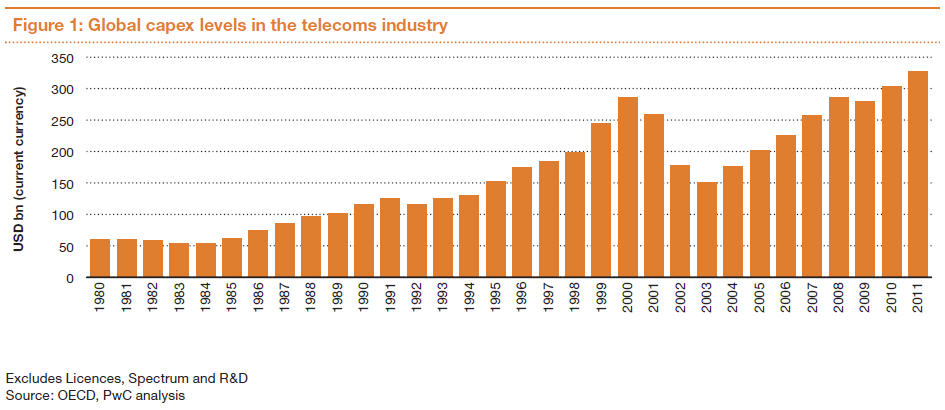

To be sure, global telecom capital investment generally has risen since 1984, even excluding important mobile service provider spending on spectrum assets. That would not be surprising, given the vast acceleration of telecom services globally, especially since the 1990s.

Generally speaking, overall levels of capital investment will not necessarily offer clues about where service providers are investing to revamp core voice and messaging services. In fact, capital investment might not be the key indicator.

Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility, in their domestic U.S. operations, already have moved to make unlimited domestic voice and text messaging an unlimited use feature of access to the mobile network. That’s a “harvest” strategy.

None of that prevents either carrier from working on other growth initiatives involving voice and messaging, though.

But the challenge remains: how much effort and investment should be put into recreating voice and text messaging?

That is a different matter than whether mobile service providers should partner with over the top app providers, work on enterprise verticals, roll out voice that works natively on LTE, or further tweak retail packaging of voice and messaging.

Realistically, it might be quite difficult to recreate carrier voice and messaging in ways that can dramatically arrest the revenue slide. At this point in time, over the top alternatives might work well enough, for their intended purposes, to permanently limit further growth of carrier services.

There still are instances where carrier voice and messaging are superior alternatives, and people will use carrier voice and messaging in those instances. What is not clear is why most people would prefer carrier versions of over the top apps, which in any case would still be “zero incremental revenue” services.