Just five years since its inception, does the strategic plan for the Australian National Broadband Network need significant revision, and if so, what sort of revision? Already, there is discussion about where to use fiber to the home and where to use fiber to the neighborhood.

Just five years since its inception, does the strategic plan for the Australian National Broadband Network need significant revision, and if so, what sort of revision? Already, there is discussion about where to use fiber to the home and where to use fiber to the neighborhood.

But are other changes, relying more on mobile access, also needed? A position paper created by the McKell Institute, and funded by Vodafone Australia, raises even more questions.

The McKell Institute paper makes the case that the Australian National Broadband Network, intended to build a new fiber access infrastructure for Australia, also can be used to support enhanced mobile Internet access, using fiber backhaul to support new arrays of small cells, and should do so, according to study author Michael Gordon-Smith.

The position paper, funded by Vodafone Australia, argues that It argues that small

mobile base stations, able to be placed on lampposts, and using the NBN for backhaul, could significantly increase and improve mobile coverage in both urban and regional Australia.

The implications are unclear. If Vodafone Australia wishes to secure backhaul from the NBN, it is allowed to do so. The McKell position paper argues only that the NBN should be recrafted to add support for backhaul to small cell sites.

In and of itself, that is not so surprising. The minimalist change is that some potential small cell sites, such as lamp posts, could become terminating access locations.

But there also is another potential complication, namely the possibility that mobile Internet access, supported by such a network, could emerge as a stronger competitor to the planned fixed line access network.

And that eventuality could emerge based on the extent of the backhaul network for small cells. What if, instead of a “thin” deployment, small cell backhaul connections were widely deployed?

“Changes in the environment are sufficiently large that policymakers and NBN Co

should consider whether strategic decisions made five years ago need any modification,” said Gordon-Smith.

The key word is “strategic,” not merely “tactical.” And one might argue that allowing a mobile service provider to buy backhaul at urban backhaul locations is fairly tactical, requiring only that the NBN be willing to install drops for a paying customer.

It is subtle, but that very statement suggests mobile Internet access could become a more-important part of the access infrastructure enabled by the NBN. The reason is simple: mobile carriers always would have had the ability to buy services from NBN, to deploy in support of small cell networks, if they chose to do so.

The position paper, in suggesting markets and end user demand have shifted in the direction of mobile, invites further shifts in NBN architecture that seemingly have implications beyond allowing mobile service providers to become customers of the backhaul network.

“The NBN was not a single decision,” but a series of choices about architecture, the priorities for rollout, and the services it will offer,” the paper suggests.

In other words, perhaps “affordable mobile broadband” is among the objectives the NBN could further, the paper suggests.

For obvious reasons, Vodafone Australia CEO John Morrow says “it is important to understand that mobile services are not a competitor to the NBN; they are in fact an ideal complement.”

Since Vodafone needs government cooperation to make such a use of the NBN possible, it is understandable that Vodafone Australia argues that adding this option would cost very little, but lead to “a broader range of compelling and exciting outcomes” for both fixed and mobile telecommunications.

Since Vodafone needs government cooperation to make such a use of the NBN possible, it is understandable that Vodafone Australia argues that adding this option would cost very little, but lead to “a broader range of compelling and exciting outcomes” for both fixed and mobile telecommunications.

But make no mistake, allowing use of NBN to create a widespread backhaul network for mobile small cells would represent a distinct competitor to the fixed access network. On the other hand, mobile networks would then become customers of the NBN as well..

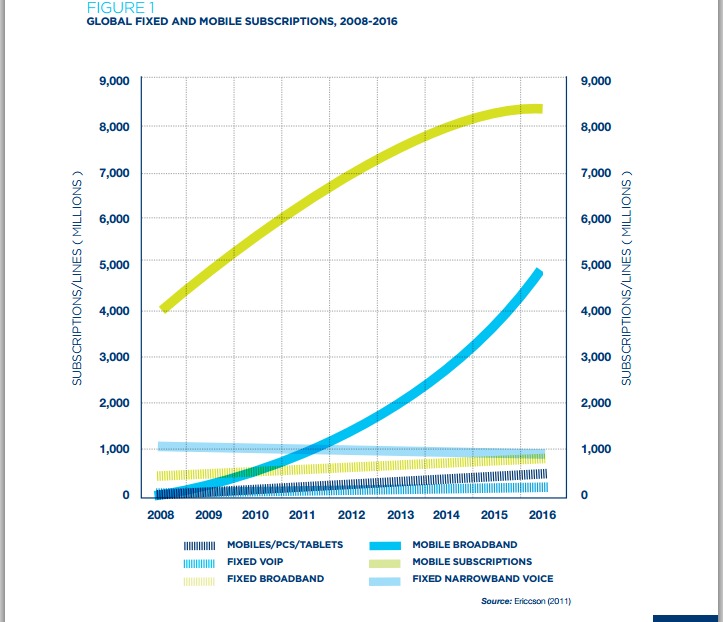

“The NBN project commenced in 2009 as a means to upgrade Australia’s fixed telecommunications infrastructure,” Gordon-Smith said. “Since then mobile broadband,

smart phones and tablets have recreated the broadband landscape.”

Gordon-Smith argues that a “national broadband network that endeavors to benefit both the fixed-line and mobile broadband networks would...transform Australia’s telecommunications landscape.” And so it might.

The position paper only argues that the NBN infrastructure is well placed to deploy more “micro

cells” that increase capacity in areas where data traffic is high, especially shopping centers, schools, cafes, universities and public spaces.

Even in such a spot deployment, offload of traffic to the small cell network makes the rest of the mobile network more capable as a substitute for fixed Internet access.

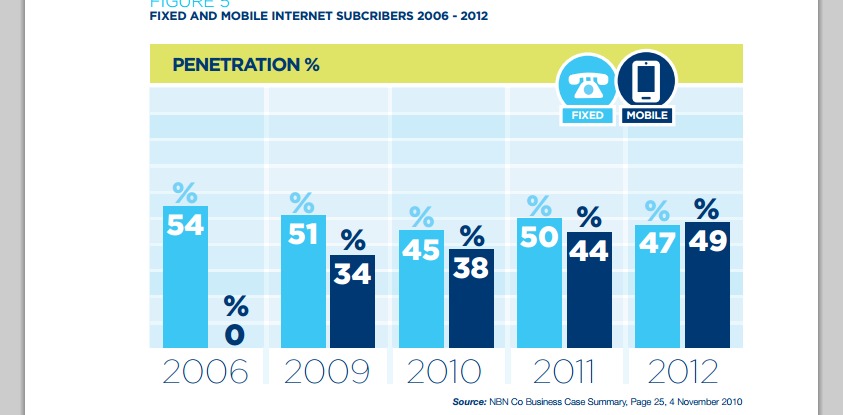

Of Australian Internet subscribers in 2012, 47 percent accessed the Internet using a mobile phone, while 23 percent accessed the Internet via a mobile broadband device, the paper notes.

Just how big a change Vofafone Australia contemplates is unknown.

Adding fiber to small cell locations might, as the paper suggests, be a slight change. But it is a small step to contemplate how extensive such a backhaul effort ought to be.

Conducted extensively enough, a small cell network, originally envisioned as an augmentation network to add more capacity or coverage in high-traffic areas, might also deliver more capacity even in some residential areas.

That would be a strategic change, indeed.