The way “communications” problems are perceived, markets created and business models are created has undergone a fundamental shift, enabling all “over the top” business models.

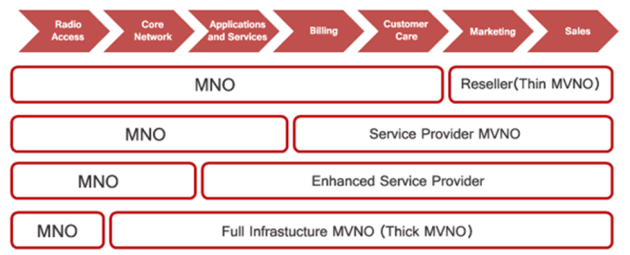

That creates big new opportunities for all sorts of firms that do not “own facilities” or physical networks. The existence of mobile virtual network operators, huge Internet app businesses, wholesale-based telecom companies and platforms to support business operations on a virtual basis provide examples of the new approaches.

The shift in business possibility is hard to grasp using old categories in the value chain.

In the pre-Internet era, all networks were purpose built and ownership of the apps and services were integrated with the ownership of the networks that delivered those services.

By definition, Internet Protocol networks are general purpose networks, and by design, IP separates the ability to create apps, services and business models from the need to tightly integrate apps with network ownership.

Think of “cloud computing” as another example of the separation of physical facilities from creation and delivery of apps and services. Wi-Fi provides yet another example of app access divorced from ownership of access facilities.

So “loosely-coupled” value chains allow value chain participants to pick and choose the places they wish to focus. That explains why Facebook, Google, Amazon and others create apps, provide Internet transport or access, build and market devices, finance the creation of content and function as content distributors.

In other words, at a fundamental level, “over the top” is the way all applications are designed to operate, even if, in some cases, the owners of physical networks also create and distribute such OTT apps.

Think of the other implications. The fundamental difference between a telco, cable TV company, satellite network or fixed wireless network, and virtually any other retail provider in the content and communications business, is whether physical access networks are owned.

source: Frank Rayal

MVNOs, OTT app providers, Wi-Fi hotspot network aggregators, cloud-based services, content producers, studios, neutral co-location exchanges, competitive local exchange carriers, system integrators and others all use or buy services from networks, but do not own them.

The application layer truly is separate from the physical and transport layers.

The other obvious implication is that suppliers now have huge amounts of freedom to create complex or specialized offers; geographic scope; customer segments; marketing strategies and business roles.

A logical corollary is that although some of the new contestants are huge and global; many more are regional or national; while most are “smaller” and more specialized. Almost by definition, specialization implies niches.

Niches, in turn, imply more-limited scale. In global markets, scale is essential; lack of scale dangerous. In regional, national or local markets, scale is less a requirement.

The key take-away, from a business model perspective, is that most contestants, in most markets, will be smaller, and lack scale, compared to global suppliers we used to think of as “tier one” telecom providers, or Fortune 500 companies, by way of analogy.

Though lack of scale is a weakness for a global supplier, scale is more nuanced matter for most

companies. Most OTT participants across every value chain can build a sustainable business without scale (in a global sense).

What is difficult, though, is a way to create more value, and find partners, when the number of potential roles and suppliers is overwhelming. If you want to know why specialized marketplaces, conferences, trade shows and other venues exist, that is why.

Most smaller OTTs cannot find potential partners using the same venues dominated by tier one suppliers with scale.

The biggest take-away, though, is that nearly every company, in every value chain or market, now operates “over the top.”

That also implies that any participant can create new roles and enter new market segments by partnering with other OTT suppliers. Look around, that is a hallmark of business strategy for nearly all providers in the broad communications and content sphere.