Some confusions are a danger in stories one sees about broadband access or telecom industry revenue. The ability to buy a product (is a gigabit service available for purchase?) is confused with consumer decisions about what to buy.

This can happen when reporters mistake “take rates” for “passings,” for example. It is one matter for an internet service provider to build, or not build, facilities with specified capabilities in an area. It is something else altogether which actual products customers choose to purchase.

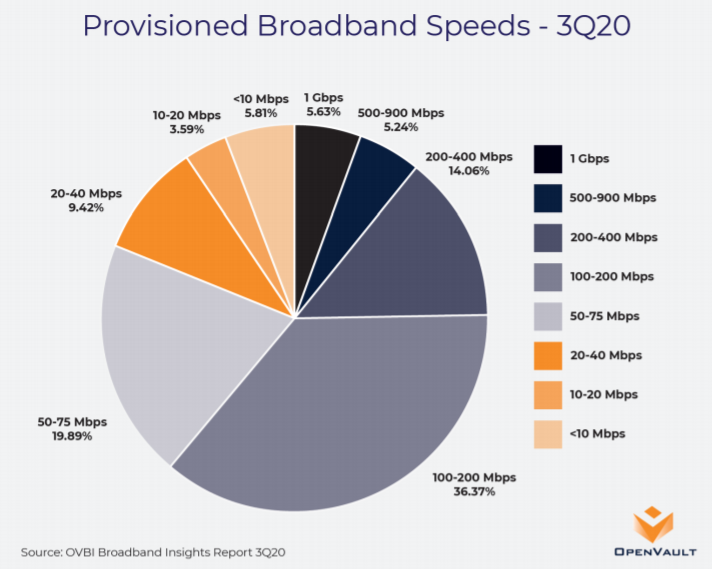

For example, the fact that most people do not buy a 1 Gbps internet access service does not mean it is not available. In the third quarter of 2020, for example, about five percent of customers purchased a gigabit service, says Openvault.

But the cable industry alone passes 80 percent of U.S. homes with gigabit service and has 70 percent of all the internet access customers. Clearly, most customers are choosing not to buy.

source: Openvault

“Telco revenue” is another area where confusions can arise. Within the industry are many distinct revenue sources, earned by different types of industry segments. Chip suppliers, software suppliers and network infrastructure suppliers, for example represent one part of the industry. Service providers, system integrators, device suppliers and applications requiring internet access are different parts of the ecosystem.

The necessary caveat is that “industry revenue” reports can be misinterpreted to include some, just one or all of the segments. Perhaps an equally great danger is misinterpretation of overall revenue in even a single segment. When there is a dominant revenue source, and many smaller sources, trends within each source can be obscured.

Total revenue can grow even when some component revenue sources are shrinking, for example.

One common area of misunderstanding is mixing up infrastructure supplier and service provider revenues. The reason is that market research firms more commonly study infrastructure supplier markets than “service provider” markets. That is where the money is, simply put.

But it is one matter to forecast sales of routers, radios, optical fiber or network management software, quite another matter to forecast sales of communications products to businesses and consumers. And yet that confusion happens.

Consider a new report by ABI Research stating that “global telco cloud revenue will grow to US$29.3 billion by 2025, up from US$8.7 billion in 2020, at a 5-year Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 27 percent.”

Nobody should accuse ABI Research of not understanding what it has researched. It clearly knows.

On the other hand, one cannot be clear from the press release what precisely was studied.

“The telco cloud growth will be driven primarily by cloud infrastructure-related investments, such as Virtual Network Functions (VNFs), Management and Network Orchestration (MANO), and Cloud Native Functions (CNFs),” ABI Research says. “By 2025, the telco cloud market will be worth US$10 billion in North America, US$9 billion in Asia-Pacific (APAC), and US$8.2 billion in Europe.”

So here is my own confusion. I cannot, with certainty, ascertain what that means. Are the figures referring to purchases of cloud infrastructure to “do cloud computing,” sales of cloud computing products to retail or wholesale customers?

The former instance represents “inputs” so telcos can do cloud computing; the latter might represent sales of cloud computing services to customers. Perhaps both are included. The point is that this is not clear. The language suggests the figures represent what telcos will buy from suppliers to create cloud computing capabilities, not the volume of sales to customers of the cloud computing capabilities.

Likewise, ABI Research says “5G network slicing revenue stands to create approximately US$8.9 billion by 2026 at a CAGR of 76 percent, arguably a drop in the bucket for Communication Service Provider (CSP) service revenue.” That seems clear enough.

Network slicing might generate nearly $9 billion in revenues for global telcos providing virtual private networks to customers.

The same paragraph also includes this, however: “the jury is still out who captures what parts of the bigger emerging 5G edge and network slicing ecosystem.” That can be interpreted in more than one way.

Are revenues generated by edge computing considered to be part of 5G network slicing? Or is “emerging 5G edge” referring to the earlier-mentioned VNF functions? Or was 5G edge a separate part of the forecast effort, and the statement “who captures what parts” simply points out that it is not clear who the winners are in telco edge, network slicing or cloud computing?

My point is simply to note that I cannot determine, on the basis of the published document, which of those understandings--or others--might be accurate. ABI Research clearly understands what they meant. I do not.

That happens more than one would suspect, when you read press releases as part of your work. Based only on the reading of the press release about the forecasts, one cannot be sure what ABI Research meant. So I cannot report what their findings were, clear in the knowledge that I understand what was meant.