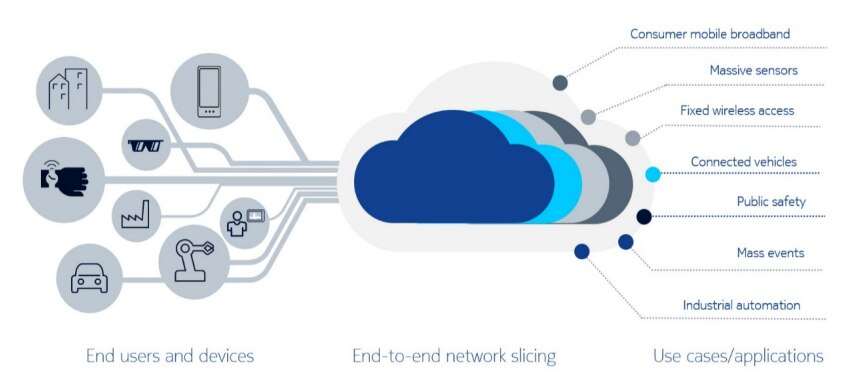

Among possible new revenue sources created by 5G, network slicing is expected to support advanced connectivity use cases for enterprises and governments that are primarily, though not exclusively, driven by untethered end points.

Most observers now believe 5G revenue growth will be disproportionately driven by new use cases and value for enterprise, business and government.

In large part, that is because businesses are expected to be the buyers of edge computing, network slicing and internet of things sensor applications.

That noted, consumer revenues in Europe, for example, are stable at about 68 percent of total revenue (mobile and fixed). In some markets, business revenues could range from 30 percent to 40 percent of total. Smaller providers might generate only about 15 percent of total revenue from business segments.

The issue is how much additional 5G revenue lift might be possible, from network slicing, for example. Some believe the connectivity portion of the market is fairly small, despite the hype.

How small? Less than $1 billion globally by 2026. That is hardly a “market” at all, by global telecom standards. That noted, value sometimes is monetized in other ways, such as higher new account rates, lower churn, higher gross revenue, lower capex, lower opex or some combination of those benefits.

source: GM Insights

A network slice is a virtual network created through a 5G core network able to maintain private network features all the way to the end point. In principle, a network slice should be easier and faster to create and tear down, with advantages for temporary networks or use cases including disaster recovery, large events or other instances where unexpected--but temporary--demand emerges.

source: Nokia

Mobile gaming is one consumer use case while internet of things applications are the best examples of enterprise or government use cases.

Network slicing allows creation of virtual networks whose characteristics (bandwidth, speed, latency, reliability, and security) can be optimized. Network slicing offers a way to create virtual networks with performance characteristics optimized for lead applications.

Mobile gaming using virtual reality or artificial reality might benefit from latency and bandwidth assurances. Other use cases in the financial industry might benefit from enhanced security and network availability guarantees.

In the fleet management industry, different core functions might benefit from use of distinct network slices. Low latency and ultra-reliable performance might be best for traffic notification, where infotainment requires higher bandwidth but less need for low latency or robustness.

It is conceivable network slicing protects core transport bandwidth for fixed wireless operations, since fixed wireless peak bandwidth usage might be an order of magnitude higher than typical mobile data requirements.

Quality of service also has been a driver of product pricing differentiation. Business services with QoS guarantees, support services reaction times and financial advantages for customers if the policies are violated, have been a staple of communications product pricing for decades.

The ability to support 5G network slicing in the core network, all the way to the mobile edge, is supposed to create new product capabilities, such as networks optimized for particular parameters.

Ultra-low latency performance; bandwidth guarantees, security or performance predictability will be touted as values of network slicing, a new way of creating virtual private networks.

Network slicing value for retail customers, though, will have to be proven. One might argue that edge computing is a functional substitute for many network slicing use cases, for example.

It would be fair to note that connectivity providers often have developed and offered many features and services they believed customers would want. The catch is that revenue for connectivity providers is the cost for enterprises, businesses and consumers who are asked to buy and use the features and services.

If ultra-low-latency applications are those which could benefit from network slices, one alternative is to do commuting at the edge, and not sending data across wide area networks that are optimized for low latency. In other words, edge computing might often be a functional substitute for network slicing.

In many use cases, the value of ultra-low-latency computing is supplied by edge computing services, with non-real time backup across wide area networks.

Perhaps ironically, consumer customers who have few other alternatives might be good candidates for internet access with quality of service features a network slice offered by a connectivity provider, providing governments deem this lawful. Network neutrality rules often var the offering of consumer services with quality of service guarantees, for example.

Gaming services, work-from-home conferencing and ultra-high-definition video are among potential consumer use cases for network slicing, where lawful.