We might all agree that telcos would prefer to build their next-generation networks on fiber to the home. We might also agree that the business case remains difficult in perhaps half of all locations.

For that reason, 5G fixed wireless has gained traction in some quarters, and might be increasingly attractive to others if fixed wireless traction is gotten.

AT&T now has about 15 million homes reachable with its fiber to home facilities, with plans to expand to about 30 million locations by about 2025. All together, AT&T’s fixed network passes about 60 million locations, however.

So the business model--as presently constituted--does not seem attractive for FTTH in about half the total fixed network passings, at the moment. Whether AT&T believes fixed wireless will be important in that regard is less than certain. Up to this point, AT&T has not been as bullish on fixed wireless as Verizon or T-Mobile.

But AT&T does have national 5G assets that could underpin a wider move to fixed wireless, even if executives do not prefer that strategy at the moment.

Other major operators without 5G assets would have to rely on partner agreements before such a strategy would make sense.

Lumen Technologies has about 15 million homes in its access network footprint, 2.5 million of which are passed by the fiber-to-home network. So less than 17 percent of locations presently are deemed feasible for FTTH.

With 21 million locations served by the access network, that implies about six million business locations. Perhaps more important, Lumen now has about 97 percent of all U.S. enterprises within a five-millisecond latency range.

After partnering with T-Mobile for 5G access, Lumen argues it can span “the last 100 feet” of the access network in that manner.

One area where AT&T should be able to improve is FTTH take rates, which have been at about 35 percent of marketable locations, and might now be up to 37 percent, at the end of the third quarter 2021.

On the other hand, it appears that take rates for new FTTH accounts might in most cases--80 percent according to AT&T CEO John Stankey--be market share taken from another provider. If that continues, it is reasonable to suggest that AT&T could eventually reach 50 percent share of the installed base, up from the 30 percent or so share it has gotten over the last decade or two.

At the moment, AT&T’s rule of thumb is that unless 40 percent share is possible, new FTTH does not make sense.

Verizon and T-Mobile, on the other hand, are much more bullish on fixed wireless, for reasons related to their present revenue models. T-Mobile has had zero share of the home broadband market, so fixed wireless offers an opportunity for top-line revenue growth that by shifting just a few percent of market share could generate billions in new revenue.

Verizon now says it will pass 15 million homes with its fixed wireless services, using both 4G and 5G, while total fixed wireless accounts at the end of the third quarter 2021 were 150,000, of which 55,000 were added in the third quarter alone.

In the past Verizon has talked about a fixed wireless footprint of about 50 million homes as a planned-for goal as the C-band assets are turned up, possibly by the end of 2021.

Most of that coverage will occur in areas outside the Verizon fixed network territory. At the moment, about half the Verizon fixed wireless customers represent new accounts, while half are existing Verizon customers.

“I would say, there are probably, roughly, half and half,” said Hans Vestberg, Verizon CEO. “Half meaning coming from our existing base and half we're taking from other suppliers.”

Significantly, Verizon also reports that fixed wireless average revenue per user is “similar” to a mobility account. That suggests that most of the installed base is on 4G or lower-speed 5G at the moment, and also suggestive of pricing suggesting that most customers also use Verizon for mobility service ($40 a month for Verizon mobility customers, $60 for non-customers).

Some of us would expect ARPU to begin climbing as more of the customer base adds services using millimeter wave and mid-band spectrum. The pricing for those plans runs from $50 a month (Verizon mobility customers) up to $70 a month (non-mobile subscribers).

As will be the case for 5G generally, Verizon fixed wireless might come in three flavors. Some customers might only be able to buy 4G versions, which are the most speed-constrained, and generally topping out somewhere between 25 Mbps and 50 Mbps.

Most customers will be able to buy mid-band 5G fixed wireless, which likely will be able to support the 100 Mbps to 200 Mbps services most households buy at the moment. Some lesser percentage of locations will be able to buy the wireline-equivalent millimeter wave services operating up to a gigabit per second or so.

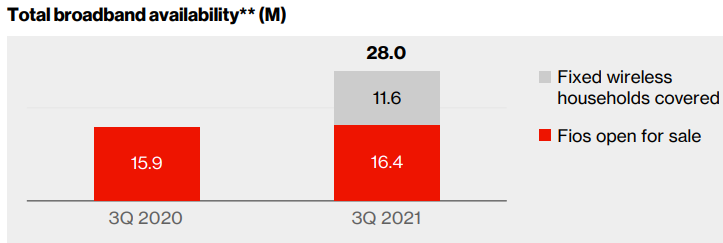

Over the last year, though the fiber-to-home footprint grew by 500,000 locations, the fixed wireless footprint added 11.6 million locations.

In fact, fixed wireless now accounts for about 41 percent of Verizon’s home broadband passings.

source: Verizon

It remains to be seen how many customer accounts will be driven by fixed wireless, to be sure. In the past, many observers have suggested fixed wireless suppliers can get take rates in the 15 percent to 20 percent range.

In a saturated market, those gains largely represent market share taken from another supplier. So the market share implications are quite significant, representing a change between 30 percent to 40 percent in overall share.

The expansion of millimeter radio and C-band radio assets will be important. Roughly half the U.S. home broadband base has been content to buy service in the 100 Mbps to 200 Mbps range.

C-band will help boost fixed wireless into those ranges, while millimeter wave will enable speeds approaching the top tier of consumer demand (gigabit service).

Such lower-speed home broadband might appeal to customers content to purchase service operating at the lower ranges of bandwidths at or below 50 Mbps. That still represents 10.5 percent of the market, according to Openvault.

Notably, the third quarter 2021 earnings report was the first ever when Verizon actually began reporting fixed wireless subscriber growth. That is normally an indication that a firm believes it has an attractive story to tell, with volume growth expected.