Language always matters. Definitions and assumptions always matter, because the truth matters. Methodology matters, in that regard.

The NPD Group says only 50 percent of homes in the continental U.S. have “true broadband speed of 25Mbps download or higher.”

That can be--and will be--interpreted at least two ways. It could mean that internet service providers are way behind the curve in making quality broadband available, or it could mean that consumers choose not to buy it.

The former is a failure of supply; the second is a consumer choice. It matters which we are talking about. In fact, Openvault test data does not support the NPD assertions. In the third quarter of 2021, for example, 9.8 percent of actual consumers had test data showing downstream speeds “less than 50 Mbps.”

The percentage of customers unable to get 25 Mbps obviously is less than that.

Though “average” speeds change all the time, the Openvault data show that by the third quarter of 2021, about 66 percent of all U.S. internet access buyers were getting speeds between 100 Mbps and 400 Mbps.

source: Openvault

While it might have been true that half of U.S. consumers were buying services operating between 100 Mbps and 200 Mbps a year earlier, it was by the third quarter of 2021 very hard to determine how many were really buying services unable to meet the FCC definition of 25 Mbps downstream.

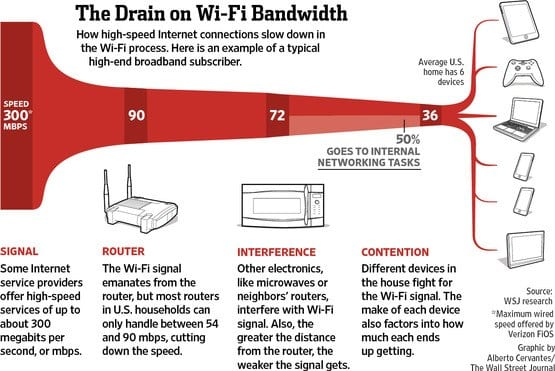

What also is undeniable is that most speed tests are conducted by consumers using Wi-Fi. That means the tests understate speed, as Wi-Fi speeds often are many times slower than delivered ISP speed.

The point is that ISP delivered speeds quite often degraded by performance of the in-home Wi-Fi networks, older equipment or in-building obstructions. Actual speeds delivered by the internet service provider to a router are one matter. Actual speeds experienced by any Wi-Fi-connected device within the home are something else.

source: CMIT Solutions

In practice, Wi-Fi speeds can be an order of magnitude slower than the speed actually delivered by the ISP. So when a consumer using Wi-Fi measures 25 Mbps, the delivered speed can be as much as 250 Mbps.

NPD Group says about its methodology that “the report is based on a combination of sales data, speed test results, consumer surveys, FCC data and other sources.”

That implies demand side dales data and speed test results. Consumer surveys can be either demand or supply side based. The Federal Communications Commission data tends to be supply side (state of facilities and availability).

To be clearer, what NPD likely means is that 50 percent of U.S. consumers choose to buy internet access at speeds less than 25 Mbps. But that cannot be true, if other demand side studies are correct.

The storyline that U.S. internet access is slow or expensive seems irresistible, even if it is questionable. A study by Speedtest of 2020 internet access speeds showed the United States had the highest performance of all countries who are members of the G-20.

source: Ookla

So much for the demand side. On the supply side,

A recent study by the European Telecommunications Network Operators association says prices are not high.

“In fact, 34 percent of homes receive internet access at speeds of less than 5 Mbps, including 15 percent that do not have any internet access. The key phrase is “receive.” It is the speed they purchase.

There are other important nuances. When do people take speed tests? Primarily when they are having a problem. Almost nobody routinely takes speed tests when performance is untroubling. So there is a bias to the taking of speed tests when networks are most congested.

Is it possible that half of U.S. homes do not receive 25 Mbps? It seems highly doubtful. If there are 10 concurrent devices active inside a home, might each device see performance that looks like “less than 25 Mbps?” That is possible, if all 10 devices are simultaneously active and delivered speed is about 250 Mbps and all the devices use Wi-Fi.

But to argue that “half of U.S. homes” do not “receive” 25 Mbps seems contradicted by available data on actual usage. And that is just the demand side.

Between 60 percent and 80 percent of U.S. home locations can buy gigabit service if they chose to do so. Not all do so.

But that reflects a consumer choice, not a failure of supply.

It is highly likely that at least 80 percent of U.S. homes can buy internet access at speeds no lower than 500 Mbps and 1 Gbps if they choose to do so. Over time, as average supplied speeds climb, they will eventually do so.