How does Android help Google? In many ways, it is hard to demonstrate clearly. Google doesn’t charge device makers for using Android, so there is no direct licensing revenue stream.

How does Android help Google? In many ways, it is hard to demonstrate clearly. Google doesn’t charge device makers for using Android, so there is no direct licensing revenue stream.

Ironically, Microsoft gets a royalty on each copy of Android used, and can quantify what it earns from each sale of an Android device.

In fact, Microsoft makes more money, directly, from Android than Google does.

Royalties are the reason. Some estimate Microsoft earns $1 per Android device, from those manufacturers who have decided to pay Microsoft to avoid patent lawsuits. Others peg the costs higher.

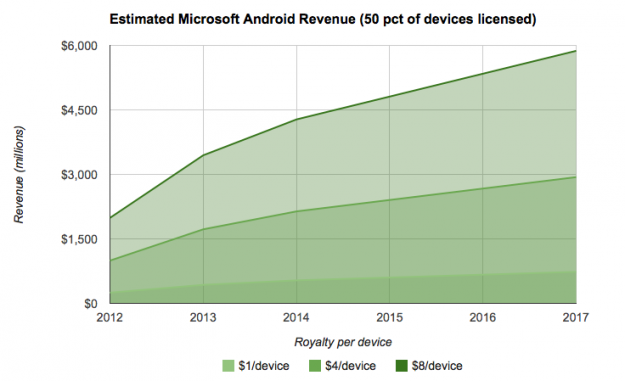

If Microsoft earns an average of $8 per Android device, Microsoft would earn $3.4 billion in 2013 from Android device sales, assuming Microsoft gets royalties on half of Android devices sold globally.

By 2017, Microsoft could earn almost $5.9 billion from Android royalties. If Microsoft collected royalties on 75 percent of Android devices sold, by 2017 that could be worth over $8.8 billion.

Device makers don’t have to pay Google to use Android, but the majority are paying Microsoft, which holds patents over multiple technologies used by Android.

Microsoft has licensing deals with almost two dozen Android device makers, including Samsung, HTC, LG, and Amazon, as well as Hon Hai, the parent company of Foxconn and China’s ZTE.

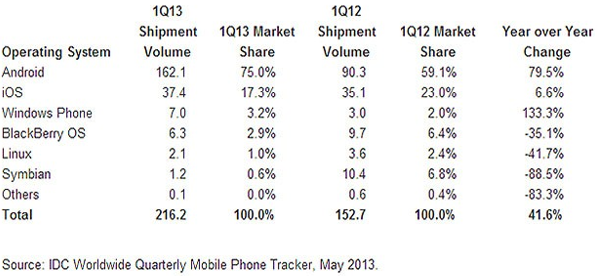

Microsoft has said that 80 percent of Android devices sold in the United States and more than half of Android devices sold worldwide are covered by Microsoft licensing agreements.

But others would argue that Google never has intended to make money directly from the spread of Android.

A more reasonable answer is that Google expects to make money when people buy apps from Google Play, or use Google search or other apps.

But even that argument is true only some of the time. A good case in point is Amazon's version of Android, where Google Play Store is not available, even though Amazon uses a modified (“forked”) version of Android.

So some make the argument that Android’s share will not, in the end, help Google very much.

So why does Google support Android, if it gets no direct benefit? You might say the obvious answer is “advertising,” since Google's primary business is selling advertising.

To the extent that web services are distribution channels for ads, then Android is a distribution channel. Google's primary motivation for incurring the cost of creating and subsidizing Android is to ensure their services always have access to market.

Skeptics might argue that Apple wins, in the end, because Apple’s revenue model aligns application provider and Apple interests, while Android might, or might not, do so.

Flurry data shows that Apple users spend more time interacting with apps than do Android users, for example.

Some would note that Apple's App Store is generating $5.4 million a day in app sales for the top 200 grossing iPhone and iPad apps.

Google Play revenue, on the other hand, has been estimated at $679,000 for the 200 top-grossing apps.

On the other hand, the indirect value of Android for Google’s revenue prospects arguably is large, if hard to calculate directly.

Some argue that Android is important because Android users tend to make more extensive use of Google apps. In part, that is because each of the major operating systems tries to drive usage to ad networks and apps affiliated with the ecosystem.

So Google might be said to rely on the ndroid ecosystem to drive a certain portion of an expected 2016 $12 billion in ad revenue.