The new infrastructure bill is touted as making $65 billion available for demand and supply investments in U.S. broadband access. And there is an argument to be made that both supply and demand investments will change consumer behavior. The issue is how much.

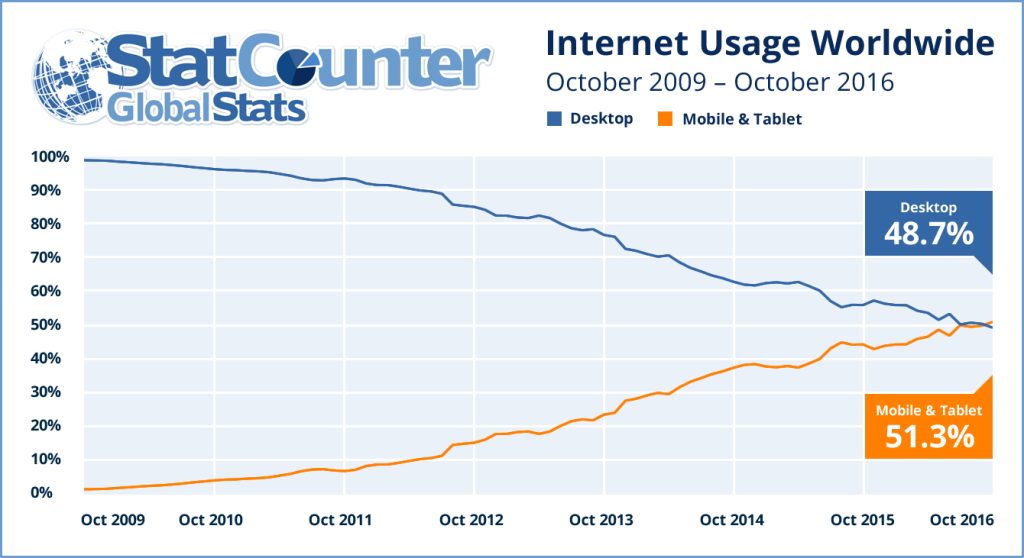

Many people use their smartphones--on purpose--for personal internet access, and do not buy fixed network service. That is a demand issue, not a supply failure. But look only at supply issues.

About 44,198 Hawaii households (10 percent) are said to have “no internet access.” It never is completely clear what definition is used. Some likely define it as having no networks which provide local service. But others might use the “25 Mbps” speed as the definition of broadband. So a household might have internet access, but not broadband.

In fact, Hawaii internet access statistics are the same as for the United States as a whole. That suggests national statistics are relevant for judging where the greatest benefit from the new demand and supply policies is to be obtained.

There are both supply and demand issues. About seven percent of households do not own a computer. If you do not use a computer, perhaps internet access is not so relevant. Recent surveys suggest seven percent of Americans do not use the internet, by choice.

By some estimates, 23 percent of households have internet access, but not at the 25 Mbps rate defined as “broadband.” There is, in other words, a difference between “internet access” and “broadband.”

There also are key implications for investment. A home that has internet access, but not at 25 Mbps, must be upgraded. But the cost to do that often is far less than building brand-new facilities to a location without existing access.

For the United States as a whole, only about two percent of households or less literally have no fixed network access. That two percent is where costs will be greatest, and also the most-isolated, cases. It might only be feasible to use satellite or some other wireless technology in those cases.

For most locations, upgrades are called for, not necessarily greenfield construction. Most of the households “not buying or not able to buy” internet access are “upgrade” situations. To be sure, telcos will have to consider ripping out copper plant and switching to optical fiber, which might require new construction.

So the issue there is the degree of benefit an average subsidy of $339 per location represents.

Income almost certainly affects demand as well. About 19 percent of households with an annual income less than $75,000 have no internet subscription.

As always, educational attainment also matters. Some 10 percent of individuals without a high school diploma or equivalent do not buy internet access.

Assume that total funding to affect demand and supply is about $300 million for the state. If half the funds were spent on supply and half on demand, that implies $150 million to build new facilities.

If 44,200 households need to be connected, that also implies capital investment and construction support of about $339 for each “non-subscribing” or “high cost” location. Some might argue that is a helpful, but relatively small change in the business case for upgrades. It might be deemed generally insufficient to incentivize new construction in very high-cost areas.

If one assumes a monthly cost of $50 for internet access, the $30 subsidy cuts costsof such plans 60 percent.

Again, however, many existing programs provide 25 Mbps broadband access at relatively low prices for low-income customers. It is not clear how much change the $30 a month additional subsidy will change buying behavior. But it certainly is reasonable to argue that the main impact is to create incentives for purchasing of higher-priced and faster-speed plans by customers now choosing to buy 25-Mbps service.

On the supply side, since one big pool of money in the bill is allocated for “unserved” areas, we should expect to see incremental investment in such areas. Since another pool of money is allocated for “high-cost” areas, we similarly should see additional investment in such areas. But the actual additional lines added should be more modest than some expect, simply because such access lines are so hugely expensive.

For practical political reasons, we are likely to see significant effort to show “big numbers” where it comes to improvement. And those results can be obtained mostly in cases where speed upgrades are possible for a wide number of lines.

So it might be reasonable to expect a relatively small improvement in total “connected homes,” but a significant increase in homes able to buy service at speeds from 50 Mbps up to a gigabit per second.

Not only is the impact likely to be wider for such incremental upgrades, but the total impact, compared to investment, will be highest as well. Assume two thirds of the supply-focused money will be spent on unconnected or hard-to-connect locations. Still, the third of funds spent to upgrade existing facilities will likely show the biggest numbers of locations that benefit.