Just what will happen to the economics of the video subscription business if Canada moves to complete unbundling of video subscription channels is unclear. It is virtually certain that programming networks will suffer.

In the U.S. market, for example, about 35 channels represent about 66 percent of all programs watched, on all channels. In a universe of hundreds of channels, that suggests most channels would either fail, or be forced to raise end user prices to compensate for lost advertising and affiliate fees (fees paid to distributors based on the number of subscribers).

In the case of advertising potential, lightly-viewed channels would retain a small fraction of their current “viewership potential.” Since advertising is sold on the basis of potential viewers, that would devastate ad revenue streams.

Also, since affiliate payments to networks by distributors also are based on the potential number of viewers, the affiliate revenue stream also would diminish.

What is unclear is the impact on service provider distributors. On one hand, a full a la carte environment would lead some subscribers to downgrade to much-smaller menus. In other words, viewers really wanting only a few channels would be able to pay less, reducing service provider revenues.

On the other hand, distributors face a growing threat of product abandonment, so some downgrading, while generating less revenue per account, would still be better than losing customers outright.

Much would depend on how any unbundling rules were promulgated. If current versions of retail packages still could be allowed, but customers also had the option of buying their channels one at a time, the revenue losses would be contained.

In other words, heavy users, watching a dozen or more channels, would still be better off buying the standard packages, so revenue from a substantial percentage of video subscribers might be largely unaffected.

Users who really only want a few channels would pay less, and distributors would lose some revenue in such cases. In between, some users would find an a la carte menu of channels costs about the same as the standard packages. In such cases, it would still make sense to buy a standard video bundle.

Almost without question, programmer affiliate payments would have to increase substantially, as networks raised prices to offset lower ad revenue. In addition, marketing costs would grow substantially, as networks suddenly would find themselves compelled to market themselves more intensively.

Some have suggested the revenue losses to service providers and networks would be quite substantial.

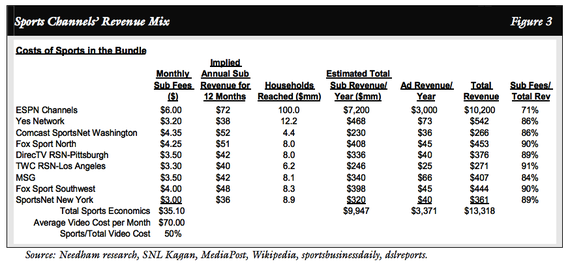

According to a study of the U.S. market conducted by Needham Insights, half the industry’s revenue—about $70 billion—would disappear if people didn’t have to pay for bundled television.

A bit less than half of that loss would probably be borne by distributions, and more than half by the networks. Needham Insights thinks only 20 U.S. networks would survive, Needham believes.

Whether that would be the case is, of course, unclear. Only after consumers were faced with real choices, and actually figured out what it might cost to go a la carte, would we see how consumer behavior might change.

ESPN, for example, costs U.S. cable TV providers about $5.15 per customer each month. In an a la carte regime, ESPN might have to raise its prices to distributors to $13 per month to make the same amount of money, according to Nielsen.

But wholesale costs could be much higher. It is impossible to estimate, at the moment. Some estimate subscribing to the ESPN family of channels alone could cost as much as $30 a month.

The issue is reach. ESPN advertising and affiliate fees rates are set on a base of 100 million U.S. homes. In an a la carte world, if subscribing households dropped to 20 percent of that amount, affiliate fees would rise commensurately, to about $6 times five, or $30.

All of that ignores the other changes that would happen, though. ESPN would look for ways to reduce its costs. And that would ripple back through the value chain, likely reducing the fees ESPN was willing to pay for sports rights.

The point is that one change--the shift to a la carte--would set off a series of other changes, of unknown magnitude. And much would hinge on whether traditional bundles remained available.

At least some service provider executives think distributors could win in an a la carte environment. That could be the case if distributors were able to keep customers they otherwise would lose, by offering more-affordable packages, with rights fees commensurately reduced.

At least some distributor executives might also believe that the only way to halt the spiral of annual price increases is for the government to intervene, by mandating a la carte wholesale offers for distributors, who then could offer a la carte to customers.

That presumably would reduce leverage held by content companies, often able to require that distributors pay to carry lightly-viewed channels in order to gain rights to "must have" networks.