Even before the internet era, telcos and connectivity providers have been torn between “being who they are” and “becoming something else.” Some with long memories may recall efforts to diversify into computing (before edge, before cloud, in fact, before client-server) or systems integration or information technology consulting.

In the internet era, many more will recall efforts to create leading app stores, become cloud computing or data center leaders. Though controversial, efforts to become content owners have been more successful.

Now many connectivity providers explore private networks, internet of things or edge computing as new fields to lead. The phrase techco is the latest version of connectivity provider efforts to become something other than what they are.

In some iterations, a “techco” is a connectivity provider that curates other digital services to add value and drive higher revenue. In a word, telcos need to become platforms. That is much harder than it often appears. In fact, few companies in any industry actually are able to become platforms, which earn their revenues in a specific way.

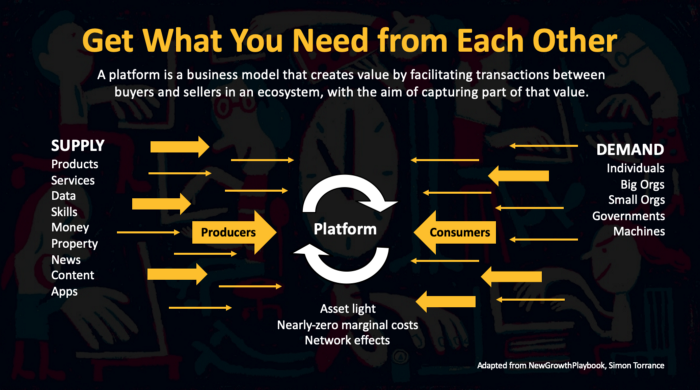

A platform earns its money by enabling transactions. It is a marketplace that matches supply with demand; products and services with the organizations that wish to buy such products.

source: Simon Torrence

It is a compelling vision, since it promises the flow of money and revenue from lots of different places to the telco.

The problem is that other participants in the value chain either do not see the value or positively reject such arrangements. Who “needs” the telco business relationship when the “layers” architecture allows app providers to reach their users and customers directly, without any such business relationships?

source: STL Partners

It is far harder than it sounds. Not everyone agrees that even successful curation or bundling of features means a connectivity provider has become a platform. A true platform implies that the actual revenue model for a firm is functioning as a marketplace where other buyers and sellers conduct transactions.

Adding features, content or value does not, by definition, mean a firm is a “platform.” It just means the supplier provides different and expanded value.

The Connectivity-Plus model might bundle cloud, edge and IoT providers’ services.

The Innovation Platform model most closely approaches a “true” platform model as it has the connectivity provider exposing its services using application program interfaces.

The End-to-end Solution model has connectivity providers assembling end-to-end solutions for business-to-customer products that might have complex value chains.

The Adjacent Acquisitions model has connectivity providers acquiring specialist companies such as IoT or security firms, and operating them as independent or partnered efforts.

Perhaps most seasoned observers would expect most connectivity providers to try either the “Connectivity-Plus” or “expose our services using API” approaches, as neither of these forces firms to radically change their business models.

Those approaches also limit execution risk.

Though most such efforts will focus on business customers and use cases, the fundamental approach has been tried often in the consumer space. The irony is that such efforts--whatever the outcomes--eventually are criticized as a distraction from “doing what you do best.”

And what telcos “do best” is provide connectivity.

source: Kearney

It is hard to argue with the vision of a connectivity provider network that is self-configuring, self-healing, and self-optimizing, enabling zero-touch operations and zero-wait for new services, as TMForum says is among the goals of applied artificial intelligence in the network.

Likewise, it makes sense to many to explore more-complicated business models that add features and services “beyond connectivity.”

But bundling new value does not change a telco into a techco. Using AI, creating a more-open network and automating are good things, to be sure. They help a telco run its business more efficiently, with less friction.

But none of that--exposing APIs, automating, using AI, open interfaces and processes, enabling zero-touch provisioning--makes a telco a techco. They make a telco a better telco.

In principle, a true telco operating as a platform would not “sell connectivity.” It would be a marketplace that allows others to buy and sell connectivity.

Few--if any--legacy telcos will ever become true platforms. To do so, they would have to become Amazon or eBay--marketplaces and exchanges--making their money from transactions. Such a “telco” would not own the actual networks and services that are bought and sold. It would simply make the transactions possible.

Few even entertain the notion, let alone are actively moving to realize such ambitions.